How JFB uses crowdsourced videos to make livestreams more fun and interactive

Published on March 31, 2021

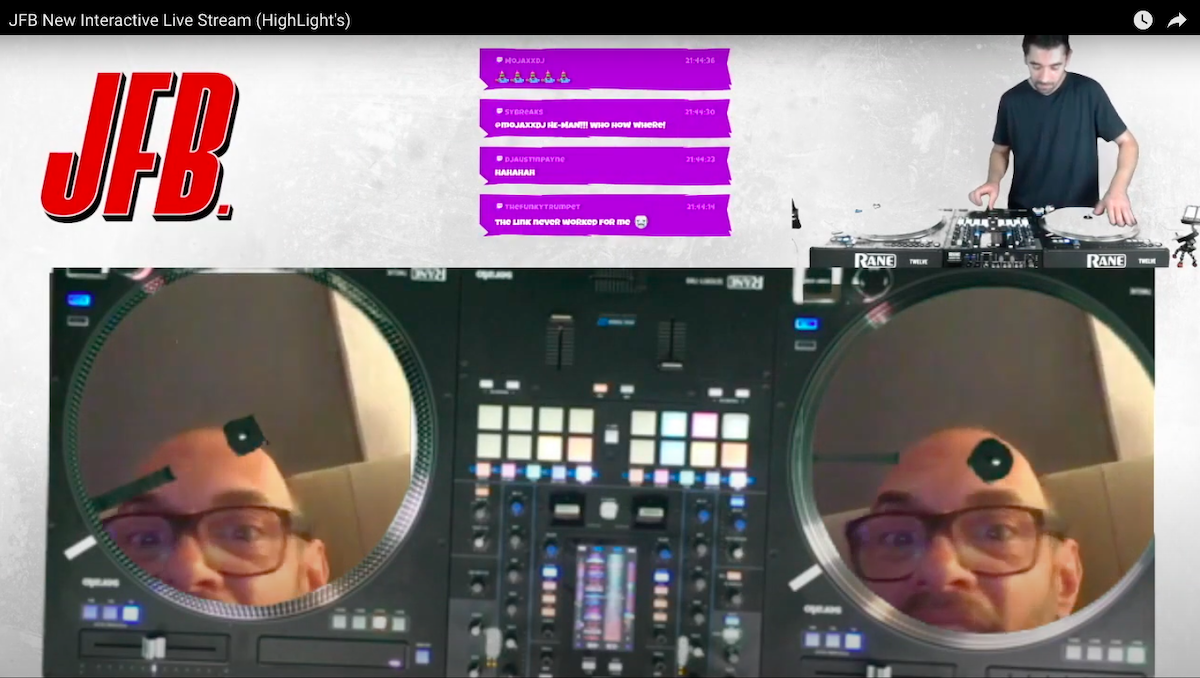

When you’re a DJ who’s used to playing off the energy of people dancing to your beats, how do you recreate that party vibe on a livestream? That’s the question we posed to JFB, a three-time UK DMC Champion who’s famous for live performances that mix music technology and crowd interaction. Here’s how JFB has been exploring new ways to keep music fans engaged online while pandemic lockdowns keep them from getting together in person.

DBX: What first sparked your interest in DJ’ing?

JFB: When I first went to a rave and started listening to mixtapes, the one thing I noticed was that the music was continuous and being mixed. I didn't really know anything about mixing. I just thought that they were making the music live on synthesizers or something because I couldn't see the decks at the parties I went to.

I was speaking to friend about the rave and he's like, ‘Oh, I'm a DJ. Come check out my setup.’ So I went to his house. This was on my last day of school, actually. He had a pair of turntables and a DJ mixer. He got the music on the record. I said, ‘Oh I recognize that. I heard it at the rave.’ He said, ‘What you do is, you put it through the DJ mixer, then you get the other record on the other turntable, then you merge the two together by keeping times. ‘Wow, that looks fun.’ I had a little bit of money saved, so I went and bought some crappy turntables, a mixer, then just started doing that for the next few months. Then it became my job.

DBX: How have improvements in technology and gear changed the way you perform?

JFB: Some producers I was working with wanted me to do scratching, so they made a sample CD of sounds specifically they wanted me to scratch. They prepared all that before they got to the studio. That was the first time I ever scratched on something that wasn't a record. I was really blown away by that. But there's no way I could have afforded that equipment.

In 2006, Serato Scratch Live came out. It was like an interface box. You plug the turntables into this box, then you plug the USB into a laptop, then all your music is in the computer. Then you have these two records, which have this thing they call the ‘noise map,’ but we used to call it timecode. It’s basically a tone on the vinyl which the needle picks up. On that tone is integrated information which tells the computer where the needle is on the record, and there's very little noticeable delay. As soon as I saw this, I just went and got it. That really changed my whole life in terms of DJing.

“That was the first time I ever scratched on something that wasn't a record. I was really blown away by that.”

DBX: Could you describe your creative process? What goes into making a routine?

JFB: Trial and error. Because I can make the audio anything I want it to be on the left and right turntables, it gives you endless possibilities. But my normal workflow is, I've got my music making program, the DAW (digital audio workstation)—I'm using Logic at the moment. I've got an empty project pre-made to start with.

I've got stickers on my records—or my platters, whatever I'm using to scratch with—and those stickers, they go round a turntable at 33 RPM at 1.8 seconds a revolution. One bar in a music-making program would be 133 point 3333 BPM. You can also set it to like 100 BPM, and it will be 2/3 of a bar. I've got one length of a revolution of a record.

Then I bounce down a silent audio WAV. I use that audio WAV as a marker. I can then open up a project, I can have any BPM. As long as I line up that marker, I then have a visual cue of where my sticker start point is going to be. I can choose where that start point is.

Imagine this is a record, I have it there where the needle would be on the record—because that's where I used to put all my stickers on records back in the day—then I can edit the audio on the left and the right deck in different sections to line up so that the start point of a new section lines up on that marker.

This allows you to be way more creative with arrangement of beat juggling, or be able to queue up sounds a lot faster. Looking at that sticker, it's so much quicker than looking at the waveforms on the screen. A lot of this sticker positioning movement becomes muscle memory as well. But basically there's endless possibilities, and multiple work processes and ways to do it.

DBX: Is that a technique you invented or something you learned from watching other DJs?

JFB: A lot of people have come up with certain aspects of it before me. But a lot of other teachers don't seem to share it. It's more from watching them do competitions. Then you see ‘Oh, what are they doing there? What's going on?’ And I've kind of got my own adaptations of it.

DBX: How do you choose your tools? Is there a particular piece of gear that's especially useful in your performances right now?

JFB: The Denon DJ SC6000M media players are great because they can manipulate the sound just like vinyl. They’ve got a crazy, amazing waveform screen that sees exactly what you're doing. It's got tons of cue points, effects, and a really good file management system as well to get organized. They're incredible.

What I’m more known for using, though, is the RANE 12’s which are like full-sized platter turntables without needles. They’re incredibly accurate and built solid. Also, the RANE 70 and 72 mixers with Serato built in are my go-to scratch mixers alongside the RANE 12’s.

DBX: For your livestream shows, you put up a Dropbox link and ask fans to upload videos of themselves that you scratch during the set. How did you come up with that idea?

JFB: Serato DJ, this program that I use to do all my DJ scratching on the computer, it does video scratching as well. You can literally chuck any video in there. Me and my friends, we’ve put on events where we've had multiple laptops networked together—a bit like Dropbox, but this is ages ago. There would be a film camera plugged into one of the laptops, and there'd be a video editor. We’d get people on stage and get them to say silly things or play their instruments or whatever. Then as soon as the person who’s capturing that video presses stop, it will automatically save it, name the file, and it would be saved on to a shared folder. Then that computer was LAN networked to my computer. I had a folder where it got saved in the other person's computer. I was scratching it through the LAN because it was fast enough to do it.

When COVID lockdowns happened, everyone was jumping into streaming. I was thinking, ‘What can I do that's interactive, that's different, that would be fun?’ I was like, ‘I've got to do something with scratching!’ I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool if I could video scratch people's faces in my live stream?’ I’ve been trying to figure out a way to do it for ages. Then I thought, ‘Oh, Dropbox has got the file request feature.’ I was like, ‘Surely that can't be that fast.’

“I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool if I could video scratch people's faces in my live stream?’ Then I thought, ‘Dropbox has got the file request feature.’”

So I did a series of tests. I sent myself a video on file requests to see how quickly it gets there. Then I was like, ‘Wait, how am I gonna send a video?’ People aren't gonna have their computers. They don't have film cameras. They've got to do it from their phone. So I had my doubts. I was like, ‘Right, I can try and see what happens on my phone.’

So I created a Dropbox file request link, then I clicked that link on my phone, and it automatically opened up a browser with a message ‘Do you want to send a video?’ ‘Yes!’ Then it automatically opened my camera, and I was like, ‘This is perfect.’ I did a test, then sent it, got it within 30 seconds, and I was literally video scratching it straightaway.

To do this, I had to have one computer to do my audio scratching, then another separate laptop to do the video scratching. On that same laptop, I had a browser open with Dropbox. I got a few friends to try it out. What was interesting, on different phones, you would get different [angles], vertical or horizontal, some of them are upside down. But luckily, the Serato video program has effects you can put on [that let you] quickly change the video angle by 90 degrees.

The really cool thing is, I did one test stream, and there were just 100 people watching on Twitch. It was actually my first Twitch stream, but some friends got a load of people to watch, and everyone was loving it. Then I did another stream for Serato DJ that was on the front page of Twitch and had loads of people watching. I was so happy how incredibly easy it was to set up.

DBX: How does the energy of an audience affect your performance? When a crowd is dancing, are you changing things up?

JFB: Yeah, always changing things up where possible. It’s very influenced by what's going on. It's very strange to just be at home in the studio interacting, even though a lot of my gigs, if I'm very lucky, I'll get to play to thousand people, but a lot of them are 100 or 200 people in a small venue. To do a live stream, suddenly you’re in front of 10,000 people, and wow, I didn't expect to be able to incorporate some interaction.

Most DJs will read the comments, then talk back, and people just love that because they feel part of it—probably even more so than they would be in the club. It gives them a chance to connect with that artist or DJ they look up to or really enjoy the music of. I've seen some really good communities growing on Twitch. But this whole video scratching thing was another level. I need to do it more.

“It automatically opened my camera, and I was like, ‘This is perfect.’ I did a test, sent it, got it within 30 seconds, and I was literally video scratching it straightaway.”

DBX: When you're able to tour and do live performances again, will you include video scratching in your set?

JFB: What would be great is a way to integrate that into more of a dance floor environment. Not all the gigs have got big screens, but you’ve kind of given me an idea, actually. I could have something set up where the promoters of an event advertised the Dropbox link at the gig. So people could film videos of themselves at the gig, then that could be placed live on top of the tracks. Then you can have effects on that with the head spinning round and around.

The first issue I thought was the audio. In the club, it’s gonna be too loud. If they get their phone out, and I try and scratch it, it’s gonna sound terrible, because you're just getting the rest of the audio of the loud venue. But simple things, like if I had another little laptop, which was networked to my computer running video, and I was getting all these videos, if I click through my Dropbox, then I could see someone's doing something weird or funny. Then I could instantly grab it, then drop it on top of a track because the Serato has a feature where you can just get video and chuck it on top of any audio track, then you can apply effects. You can make some spin around, or do crazy kind of cool things. That's a great idea. Thanks.

DBX: That's what I was imagining. Especially at venues where they did have video screens, it’d be a thrill for people in the audience to go “Hey, that's me. That’s what I sent in!”

JFB: What better way for a friend to embarrass one of their friends that's there with them?

To learn how DJs can sync their Engine PRIME collection to Dropbox, then access it remotely on any Engine OS device using the Dropbox Personal Cloud Integration (Engine PRIME, Engine OS), check out dropbox.com/apps/engine_os