Sundance Film Festival 2020, Dropbox for filmmakers

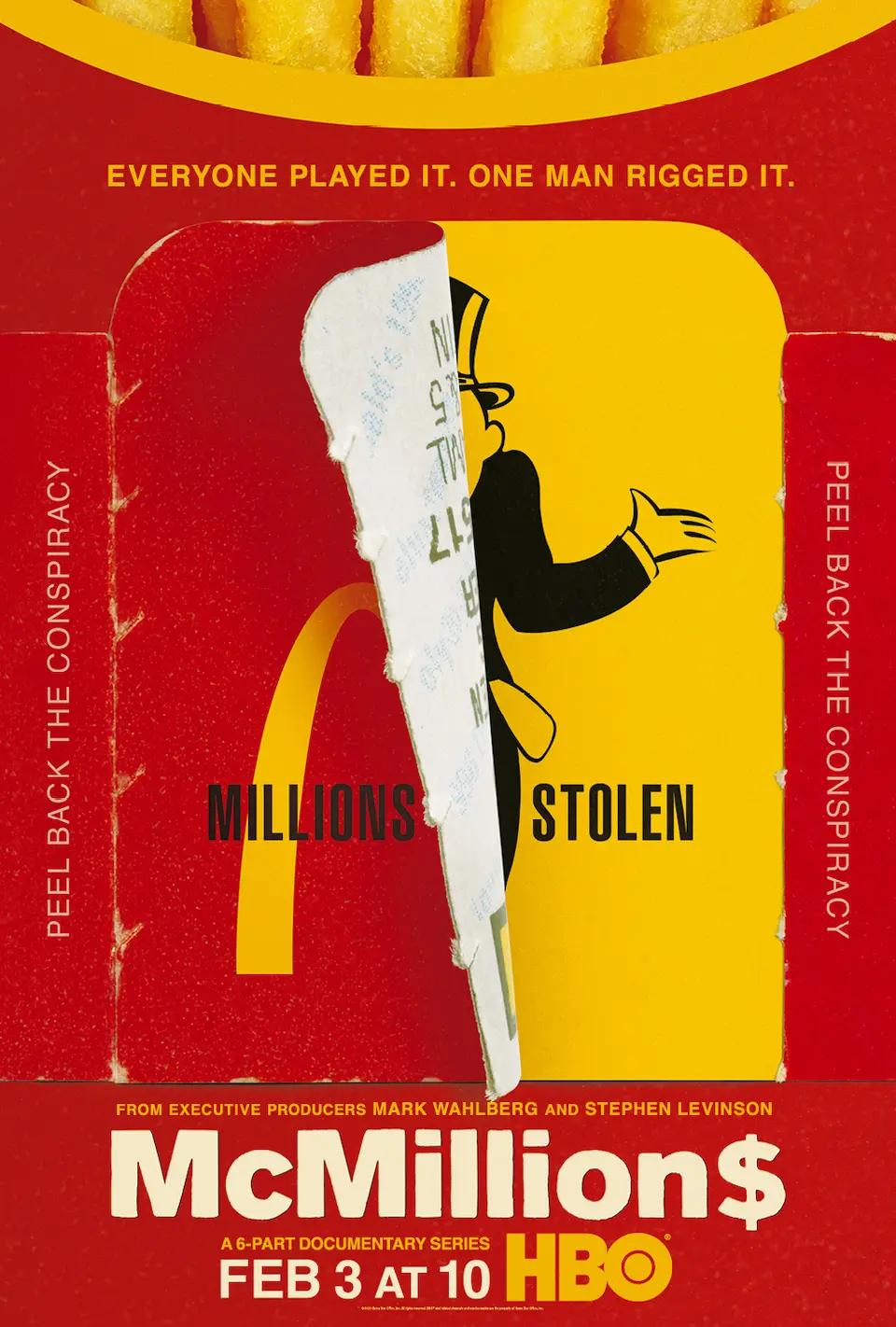

How the directors of HBO’s McMillion$ uncovered a conspiracy everyone missed

Published on January 21, 2020

8 years ago, filmmaker James Lee Hernandez was browsing Reddit late one night when he came across an intriguing topic: Nobody really won McDonald’s Monopoly game.

“I loved that game when I was a kid growing up,” says the co-creator of the new HBO documentary series McMillion$. “I was convinced I was gonna win a million dollars. My first job when I turned 16 was at McDonald's.” He couldn’t resist diving into the Reddit thread to learn more.

If you were playing the McDonald’s Monopoly game in 1990s, you probably figured your chances of winning were as good or better than the lottery. But for over a decade, a small group of players secretly manipulated the game through a complicated scam that defrauded McDonald's out of over $24 million. It took an anonymous tip to the FBI to finally bring the scandal to trial.

As intriguing as this story was, the most shocking thing was the lack of information. Determined to dig up more details about the McDonald’s Monopoly game conspiracy, Hernandez filed a FOIA request, which took 3 years to go through. After that, he was finally able to begin contacting FBI agents. Then he teamed up with his longtime colleague, Brian Lazarte, and the two began diving deeper into the story.

“There's so many details that you can’t Google, that aren’t public knowledge,” says Hernandez.

“We started to expand beyond the FBI to the ‘winners,’ McDonald's, prosecutors, defense attorneys—everyone surprised us with how rich this story was,” says Lazarte. After almost two years of self-financed research and investigation, the duo teamed up with Mark Wahlberg’s production company, Unrealistic Ideas, and decided to take it to network as a documentary series.

“When we first brought our pitch deck to HBO, their response was, ‘There's a lot of meat on this bone,’” says Lazarte.

“When we fully locked in with HBO, we were able to go on the road for about a month,” says Hernandez. “That's when we saw the full scope of everything. And it was substantial.”

The biggest challenge was trying to organize the massive amount of information that piled up over years of investigation.

After spending the first years working mostly as a duo plus one camera operator, they were finally able to fund a full-time crew. “There were a lot of people we’ve been in the trenches with throughout the years. We knew we were gonna have to dive into a really big thing, and we should all trust each other, and have a very open collaborative situation,” says Hernandez.

Even with a larger crew, though, the biggest challenge was trying to organize the massive amount of information that piled up over years of investigation.

“We had boxes and boxes of evidence and paperwork,” says Hernandez. “At one point, we had all the transcripts from the trial, and the trial spanned two weeks. That's a ton of transcripts to try and read through. So we scanned them all, made PDFs that were searchable, then put them into Dropbox to be able to access them at any point.” [Editor’s note: When you scan a paper with writing using the Dropbox app, the text becomes searchable in the digital file.] “There were times when we were out on the road filming, when we were like, ‘Wait: what does this one witness say during the trial?’ We could look it up right there.”

The wealth of material proved to be a blessing and a curse, and raised one of the most important questions the filmmakers had to ask: How do you contain a story this big?

"The fact that the landscape is really primed for people to have these stories be told over a long period of time is great.”—Brian Lazarte

“At first, you go at it with, ‘This is an extremely interesting 90-minute to two-hour movie.’” says Hernandez. “Every single time we’d get new information and learn the timeline, it just kept ballooning more and more. It starts to grow and you think, ‘Maybe it’s a couple episodes. Maybe it’s four. Okay, it’s going to be six.’”

“The landscape right now is that people are willing to watch six hours of a documentary,” says Lazarte. “Hopefully, people will see it as a long documentary that can be digested in sections. The fact that the landscape is really primed for people to have these stories be told over a long period of time is great.”

It’s not just the new distribution models that have changed the ways films are made. New technology is also making it easier for filmmakers to keep documents organized and secure.

“There were things that the FBI and the Department of Justice trusted us with,” says Hernandez. “There were pieces of evidence we have that nobody else has seen—the court transcripts, other documentation that was admitted as evidence in the case. Those were things we had in a folder we could access anytime with Dropbox.”

“Whenever we're doing an interview, we get them to fill out an appearance release that can be scanned and put it Dropbox so we don't lose a piece of paper while we're on the road."—James Lee Hernandez

Hernandez recalls when they were preparing for an interview they weren’t certain they would get. “All of a sudden we needed to know all the things that were said about that person in the trial transcripts,” he explains. “If this was 10 years ago, we would’ve said, ‘Can you read them off to us or scan the whole thing and email them to us?” Then we’d hope we can get a Wi Fi signal somewhere. Nowadays, it’s right there on my phone.”

“Whenever we're doing an interview with anyone, we get them to fill out an appearance release that can be scanned and put it Dropbox so that it's saved and we don't lose a piece of paper while we're on the road,” says Hernandez. “There's so many different things we have to do—from media storage to sending out dailies between each other—things you couldn't have done nearly as seamless or as fast 5 years ago.”

In the end, Lazarte says overcoming logistical challenges gave them a chance to try new approaches. “Challenges are really opportunities for creative flourishing. When we’d find ourselves in a confused state of ‘How are we going to make this point clear?’ We’d just tack it up on a board. Then we'd have this victorious moment that could be weeks later. When you break through and have those victories, you don't focus on the challenge. You focus on the opportunity to tell a better story.”

McMillion$ premieres January 28 at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival and February 3 on HBO.

To learn how filmmakers are using Dropbox to simplify collaboration and work efficiently through every stage of the production, check out dropbox.com/film.