How Fleet Foxes bottled up the feeling of 2021 in a music video

Published on September 30, 2021

Director Sean Pecknold takes you behind the scenes in the making of "Featherweight”

“Very tumultuous and up and down, and at times confusing and terrifying and uplifting and hopeful.”

That’s director and visual artist Sean Pecknold recalling what the last year and some change has been like for him. But he could just as easily be describing the soul-stirring music video he made for “Featherweight,” the newest single from indie folk band Fleet Foxes’ latest album Shore. (The video, made in partnership with Dropbox, is the tenth Sean’s created as the band’s sole visual collaborator.)

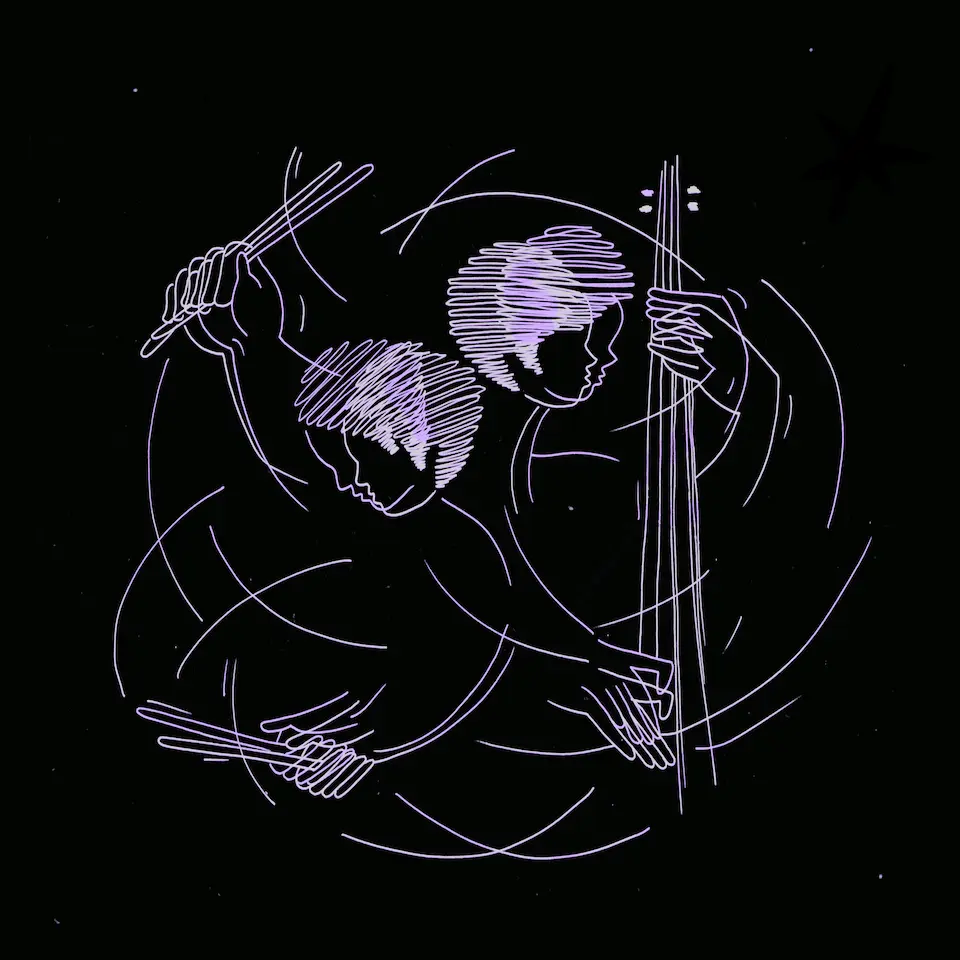

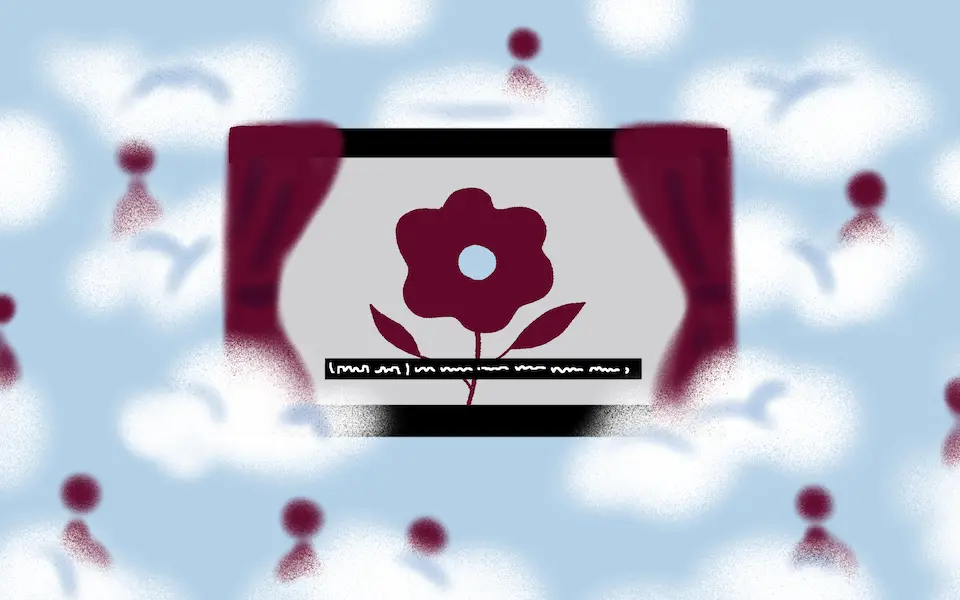

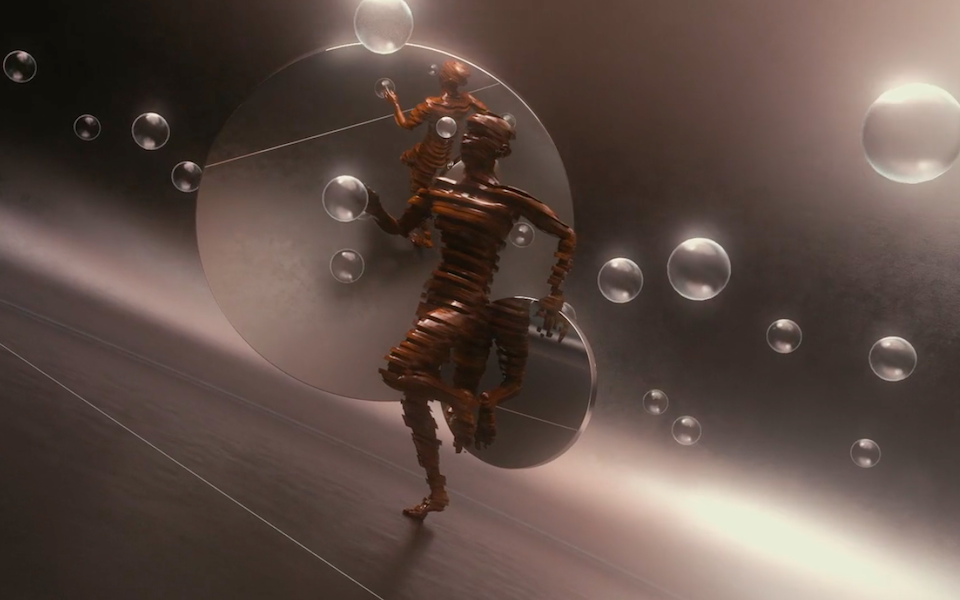

Using a multiplane camera and stop-motion animation, the video follows a young hawk “looking for a new home, looking for a feeling of renewal and safe harbor.” Nursing a broken wing in a world that feels trapped in state of perma-dusk makes his search much more difficult. We see him set course only to fall to the earth soon after, a plume of dust rising up from his body as he hits the ground. After a year plus of living in a COVID-induced limbo, it’s easy to see yourself in the hawk’s staccato flight pattern.

“Kind of every emotion you can feel in a lifetime I feel like we’ve felt, or at least I’ve felt, in the last year and a half,” Sean says. “I was reflecting on that a lot [while] making the video and putting feelings of both isolation and fear and anxiety and hoping for an end in sight or a burst of light on the horizon of darkness, and weaving those thoughts and feelings into the video where I could.”

“Yes, I… I echo that,” says Robin Pecknold, Fleet Foxes’ singer-songwriter frontman and Sean’s brother. In all the emotions and the “forced stillness” of 2020, Robin took the “opportunity to do a mental inventory” of himself while also dropping a surprise album in Shore.

“When the lockdown started hitting, a lot of the songs were pretty far along and a lot of the music and some of the lyrics were written,” Robin explains. “Even though I had bits and pieces of the music from before, the song and a lot of melodies and all the lyrics [for ‘Featherweight’] really came together in August 2020. It was the one that was the most deeply inside of lockdown.”

The song structurally and lyrically reflects the duality of its title and that time without feeling like an artifact of COVID. “I wanted the music to have this kind of weightlessness, like there was a weight [that] had been lifted,” Robin explains. “And the guitars are all kind of feathery and floating around, but there’s this kind of grounding drum element.”

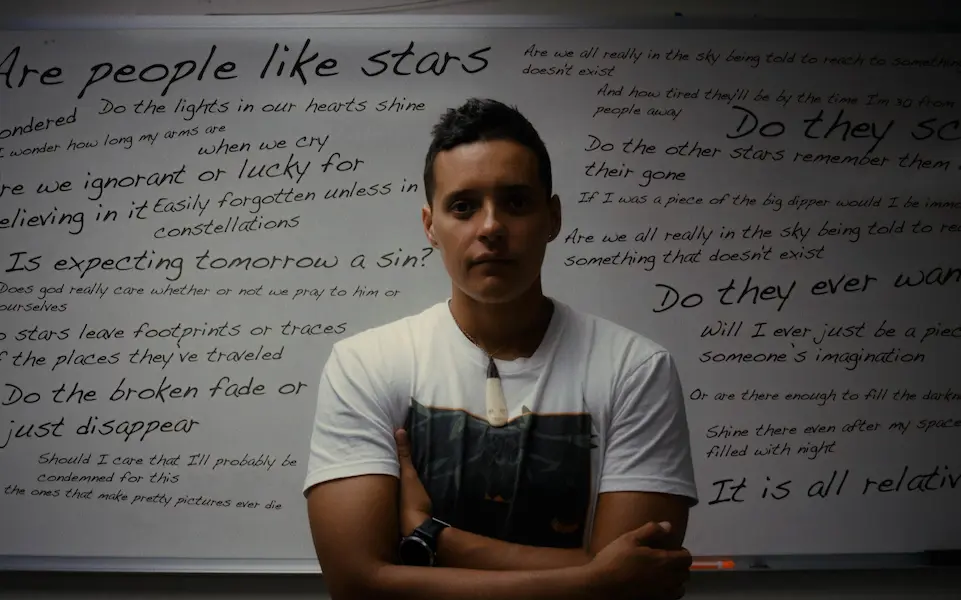

Sean found inspiration in those elements when it was time to dream up the video’s concept. After more than a decade of working together on Fleet Foxes’ videos—and a lifetime as brothers—getting the green light from Robin was a given. He had already been working on concept art with Toronto-based artist Sean Lewis for a feature-length animated film. (Lewis had also created one of the band’s first T-shirt designs in 2008—”a guy’s face with snakes, kind of a Medusa illustration,” Sean recalls with a smile.)

“I was like, ‘We have to do what we’ve been doing for the concept art as [an] animation,” he explains. “The art work was so textural and beautiful, that I really wanted to make it move.”

Sean also knew he wanted to work with a character animator this time around—and Eileen Kohlhepp’s reputation preceded her. Along with her bona fides (Kohlhepp has worked on MTV’s Celebrity Deathmatch and Adult Swim’s Robot Chicken among others), Sean realized the two had similar reference points, such as early Disney films and “1960s, ’70s Eastern European animation.”

Telling the story of “Featherweight” through stop-motion animation was a homecoming of sorts. Sean found the technique to be a refuge from computer animation earlier in his career and used it for videos from the band’s first two albums. And in the early days of the pandemic, it became a “counterbalance to all the anxiety and constant emailing and texting.”

“Stop motion causes you to have to slow your heart rate down and really kind of become meditative in your process,” Sean explains. “You can make something that is, like, so unique to the story.”

For the five-month long, cross-country collaboration, the small team immersed themselves in the song and the hawk’s world.

“’Featherweight’ was kind of the only song for which nothing at all was recorded before the pandemic happened,” says Robin. “If anyone was going to be adding to it, it had to be via Dropbox. For me, for Sean, and for I’m sure every musician trying to make their way through last year, Dropbox became this indispensable tool.”

Robin gave Sean access to a Dropbox folder of the song’s stems, that is, the individual elements that make up a track. (He also made them available to fans—now there are “a couple of shared Dropboxes of Fleet Foxes fans on Discord and Reddit where they share their remixes of the stems and their covers,” he says.) Being able to isolate just the bass or drums kept things fresh, Sean says with a laugh, but also led to “nice, happy accidents.”

“When I just heard the drums, like the dun-shh-dun,” he says, “it was actually timing out to our wing cycle for the hawk.”

“For me, for Sean, and for I’m sure every musician trying to make their way through last year, Dropbox became this indispensable tool.”—Robin Pecknold

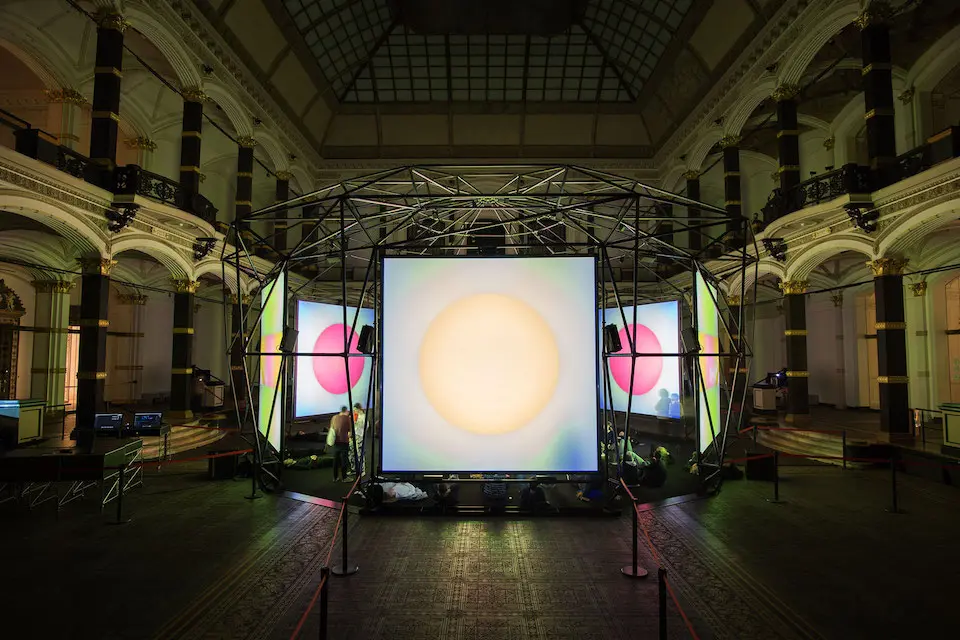

Lewis used Photoshop to create very detailed illustrations and dropped them in a shared Dropbox folder for the rest of the L.A.-based team to check out. Sean would send his notes via Zoom meetings or directly in Dropbox, and then send preliminary sequences of the storyboard sketches back to Lewis, Kohlhepp, and two other artists helping on the project.

“The process of getting from illustration on a computer to animation to a layer of art that we can put on our mutliplane stop-motion table was the biggest thing we had to solve on this production,” Sean says. “Sean [Lewis] hadn’t done it before. I hadn’t done it before. We’ve just painted on paper and done things directly in the real world and then put it on the multiplane.”

Solving it was much less harrowing than the hawk’s journey: Patrick Blanchard, the video’s art production lead, shared the Dropbox folder with an area printer to get physical copies of Lewis’ illustrations. Those print outs were then brought to the studio, where the team could cut, arrange, and light them across the multiple glass plates that give the multiplane camera its name, and its tell-tale depth effect. (Invented by German director and animation pioneer Lotte Reineger and used by Walt Disney a decade later in films like Bambi and Pinocchio, multiplane down-shooting also lends a dreamy yet tactile quality to the art.)

“It kind of became a network of like 10-12 people [who] were referencing the same folder, able to pull high-resolution files from the same place, take it all the way through many computers to the printer, [and] get it back to the multiplane,” Sean explains. “It became a circle because then I would shoot the animation with Eileen on the table, we would take those images in, export them back to QuickTime, and then it would end up back in Dropbox to then be shared as a work in progress with everyone else.”

The final product captures where many of us find ourselves now at this point in the pandemic. Past the 7 p.m. clapping for essential workers and toilet paper hoarding, but still anxious and a little isolated even as—or especially as—things open up in fits and starts around the world.

We may find ourselves feeling like the hawk does at the video’s climax: defeated and unable to go on. But salvation can look like taking a different route—and leaning on a friend who is just as broken as we are to get there. (In “Featherweight,” it’s a three-legged wolf who helps the hawk reach the end of his journey.)

“The fact that his savior is himself wounded, I think that’s this very real kind of wrinkle,” Robin says. “That’s what felt resonate to me.”

“Everyone is flawed,” Sean says, “everyone else that you know has their weaknesses, but they have their strengths that can lift you up where you need to be lifted.”

And after the year we’ve had, we can all use the reminder.

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/Karen%20O%20%2B%20Danger%20Mouse%20(photo%20by%20Eliot%20Lee%20Hazel).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/Extremely%20Wicked%20Shockingly%20Evil%20and%20Vile_Sundance19_Director%20Joe%20Berlinger%20(3).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/Bedlam%2014%20(1).webp)