Think small and embrace mistakes: Q&A with Moonlight’s James Laxton

Published on February 28, 2018

How do you capture small, human moments in a way that feels true to life? In the lead up to the 90th Academy Awards, we’ve been exploring how several different filmmakers create, collaborate, and take risks. We recently caught up with James Laxton—the cinematographer from last year’s Best Picture winner, Moonlight—to hear all about his creative process. Here’s how James thinks about film, from the importance of creative tools to the power of trusting your collaborators.

On how it feels to break into the limelight

It's been awhile since that Oscar night. How does it all feel?

Oh my gosh. Yeah—there were definitely some emotions which came about that I've never experienced before. That was all new for me. [chuckle] That kind of excitement, and anxiety, and stress, and wonderful, loving feelings as well. It was all a bit of a mixture—a stew of emotions. I walked away from that experience with a sense of belonging. We made Moonlight so far out of studio systems and no one knew who we were. We were very much off the radar. Maybe now, people have a bit of an idea as to what we can do. It definitely got us in the game.

And you are now an Oscar-nominated cinematographer!

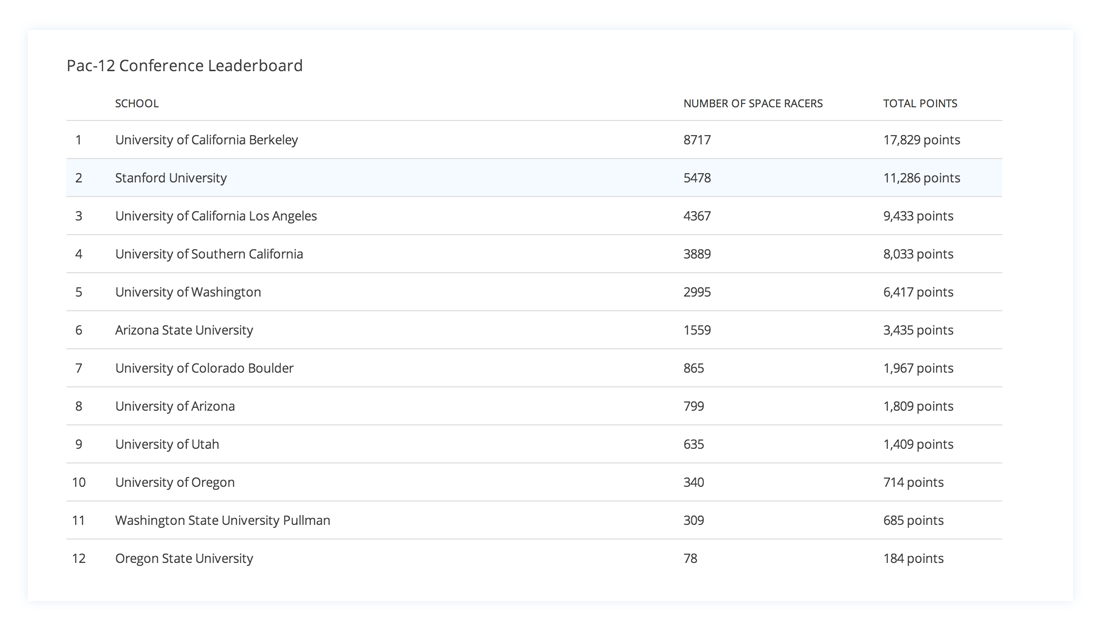

Literally every single person in that category for me is someone that I've looked up to for a number of years. [Editor’s note: The cinematography nominees last year were Laxton himself, Bradford Young for Arrival, Linus Sandgren for La La Land (won); Greg Fraser for Lion, and Rodrigo Prieto for Silence.] To be in that group of people—and associated with those names and that amount of talent—it was an honor.

It meant a great deal to me just because I wanted to be a cinematographer for a very long time. My mom's in the business, so I've known about that position since I was a child. I've been obsessed with those guys for as long as they've had careers. And so to spend time with them, get to know them, and to be honored to be nominated with them was definitely something that I'll never forget.

On how James got started with Moonlight writer and director Barry Jenkins

How do you think your craft has evolved since you first worked with Barry Jenkins on the 2003 short film, My Josephine?

It's funny. My Josephine was technically the first time we actually collaborated tangibly on a project. Our friendship came before that collaboration, because we were actually roommates. So [we’d already] watched films together, had conversations about the visual language of the medium itself. I think we fell into a bit of a collaboration that I would say it hasn't changed very much, to be totally honest.

Paramount to any process of collaboration is trust. And you gain that from experiences.

I don't know that we speak differently or communicate differently today than we did then, oddly enough. I think that has to do with this immense amount of trust that the two of us share. We’re excited about ideas we both come up with and trust one another to extend that within those parameters. That's how we made My Josephine, and it's how we made Moonlight, and that's probably how we'll continue to share ideas as time goes on as well.

On how building trust leads to creative freedom

What’s the secret sauce for a great collaboration?

There's all kinds of technical processes that one goes through to find collaboration. And a lot of that has to do with the tools and techniques that you use to communicate ideas between parties. But I think prior to that, obviously paramount to any process of collaboration is trust.

And you gain that, I think, from experiences. A family, for example, has trust because you grew up with a family, and then you have these experiences within that dynamic that then you grow out of. And then you look back and share those moments with your brother or sister, mother or father and say, "We went through this together, and now, I can trust you with anything because we journeyed and grew together as partners."

I think the same could be said for any kind of collaboration in business, or in my case, in filmmaking. So, I think experiences are a big part of it and a journey that you share with people along the way. Growing throughout that experience as artists is what made the partnership with Barry and the [entire] Moonlight team work. We opened up and took a journey in Miami for a couple of months.

One of the things that Barry does very, very well is he allows his collaborators to feel a part of that journey, and I think trust comes inherently in that process. Then you start to share ideas. If you have this backbone of trust, you can admit that you don't quite know what someone's getting at right away, but you trust in that person that they are onto something. For example, I don't know how often Barry really says no to an idea I come up with right off the bat. [chuckle] and I think I reciprocate that as well. If he has an idea, my initial instinct is always to say, "Alright, let's explore this,” even if I don’t quite understand it. Whether it's a lens choice or a lighting choice, or whatever it might be, to go along with it.

And what oftentimes happens is five or 10 minutes later it clicks—then we keep going down the path for a little while. And all that is based on this level of trust. When I come up with a wacky idea that I think is interesting, if that trust wasn't already there, I don't know that he would be open to trying it.

You might not even be on the set yet, you might just be in a conversation, you might be meeting in a cafe, you might be having dinner with someone, but the idea that you're at least with a human being who is open enough to say, "Let's go through this journey for a little while with some open-mindedness, and see where it goes." I think that's a big part of, for me anyway, what the collaborative process is all based upon.

On the challenges of working with new collaborators

So what happens when you don’t have being roommates to build upon, how do you forge a creative partnership?

It's tough, yeah. It's so hard. I think on some level it's almost like speed dating. [chuckle] You have to have a way about yourself that you can ideally, as quickly as possible, get to know someone.

The idea of how to use a tool properly, what uses it has for you—that’s always been something I've engaged with.

Aside from working with Barry, I've had projects where you're hired on to do a film, and you might have, say, four weeks of pre-production. So the idea is, within that four weeks, you have to get to know someone really, really deeply.

And that's actually the biggest challenge, more than it is technically getting the equipment out there and ordering the stuff and hiring the camera department and the lighting departments.

What's the hardest part about that four weeks, I've always found, is finding a way to understand the director's personality and vision and engagement and how they like to work. It's hard. I actually don't have any secrets about that. [chuckle]

On the importance of creative tools

What's your relationship like with technology? Obviously you're fluent in all things cameras and lenses, but are you someone who embraces technology?

Learning about tools is something I've always been interested in. My dad is a carpenter in San Francisco and so I grew up also working with him. Having this hands-on craftsman perspective of my process—I think it stems from that. The idea of how to use a tool properly, what uses it has for you—that’s always been something I've engaged with. And couple that with hanging out with my mom on set when I was a 12-year-old kid—she'd oftentimes drop me off at the camera truck and ask the guys to take care of me for the day, [chuckle] I was always excited about that because, to me, the camera department always had the cool toys.

Big crews and lots of support can sometimes be cumbersome. So we took a small crew, a short shooting schedule, and embraced that conceptually.

So I love the idea of learning about new tools, new technology, how to implement them creatively and use them to a function that supports a narrative or supports a tone that you're looking for now. That’s always been my process creatively—to have the idea first and then see how to functionally break it down to maybe make sure it's achievable on the set.

Where have you been able to create an idea by having to discover new technology or bring something new on set?

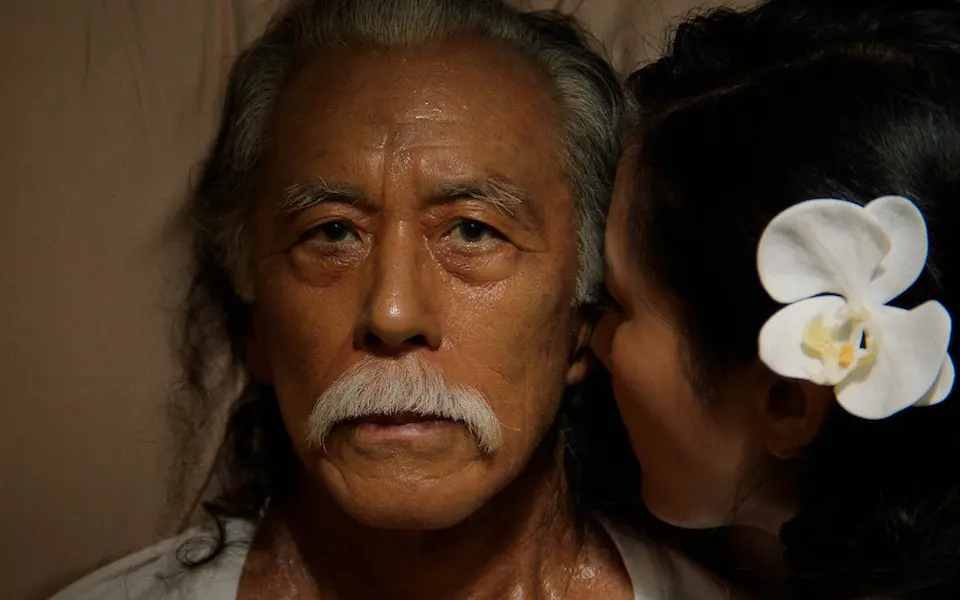

In Moonlight, the whole visual concept was all about immersiveness, placing the audience directly into the character's perspective as he goes through his journey. So for us, that meant having the lens as close as possible all the time.

And what we learned was we had to use diopters to be successful. Diopters are these things that go in front of the lens that almost look like filters, but then what they do is they allow the focus to shift to a much closer distance. And there's a lot of technical drawbacks to them. You can't, for example, go from super close to infinity on the lens, but they do allow you to place the camera much closer to the subject than you would without one.

So the idea to use diopters came after the fact. It was all about, "Let's make it so they come really close and let's see what we can do to help us achieve that idea.”

On the benefits of working with a smaller team and a lower budget

You were a one-man camera band on a 25-day shoot! How did you pull that off?

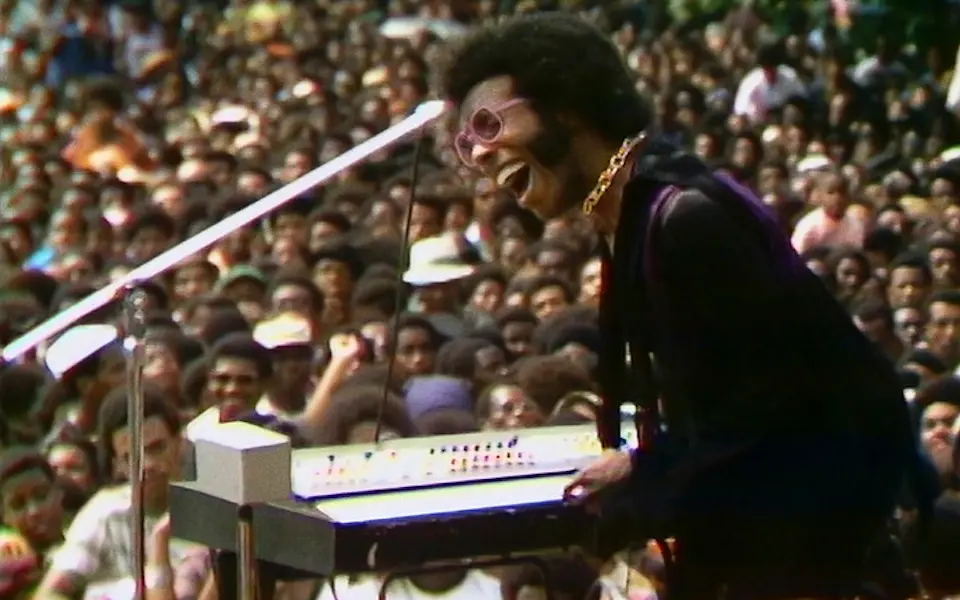

Something Barry and I like is “tempo effect,” when there's a bit of a pace to things. You can use quickness and speed with agility when you don’t have a massive machine behind you. Big crews and lots of support can sometimes be cumbersome, as well as not supportive. So we took a small crew, a short shooting schedule, and embraced that conceptually.

For example, if Moonlight was made for $50 million, it probably wouldn't have been as good of a movie, to be honest with you. [ Editor’s note: Moonlight only cost about $1.5 million to make.] We might be driving nicer cars but the movie probably wouldn't be as good.

And I think that's a lot to do with just the material matching the creative. Clearly, we pushed hard and we definitely did as much as we could with the money, so we really stretched the dollar very far. But the roughness, the way the camera moves sometimes in a non-technically precise fashion, I think that only adds to the experience—you feel the artifice of the camera in that.

I love watching for intimacy between characters through the lens. I get a lot out of having an experience in a moment, and then being able to be express it and share it with an audience.

I think that can be a good thing at times. It can be disarming. It can maybe be reminiscent of home movies on some level. Because your stepfather's operating or your cousin's operating the camera and it's crazy.

But I think all these things subconsciously lend themselves to some kind of honesty and truth that I think we all associate with as audience members. So, [chuckle] this is a weird answer, but on some level, I think, that the pace and the tempo and the small crew only adds to the film and the end result.

So the limitations that you had in terms of time and budget were things you embraced? Because it matched what the story was trying to achieve?

Yeah. For example, take the swimming scene. We shot that scene in an hour and a half. [chuckle] Because, a lot of it had to do with a storm approaching and things like that, but there’s energy that comes from just getting the camera out there quickly, doing a quick lesson, almost live on camera with those two fantastic performers.

I think that energy was present in that moment physically, in Miami in the oceans on that day. It’s very palpable in those images when you see them. As an audience member, you react to them accordingly and you feel very present in that moment too. If we, for example, shot that scene in a big tank in Los Angeles in Hollywood—with blue screen all around it to make it perfectly exposed—we would complement it later with the effects. But I think all that tangibility and emotional truth that you feel [in the final scene] comes when you see those mistakes, when you see the sky sort of over-exposed at times. All of those things are inherent in the speed and process that we're going through on that day. I think that's a great example of where our process, while being challenging, actually was a massive aid to the end result.

On finding your source of creative energy

You mentioned energy there. Where do you draw your creative energy? Where does that come from?

I have an obsessive trait of being very quiet and watchful of people's interactions. Then what I get to do on set is be peaceful and watchful with characters' interactions. I love watching for intimacy between characters.

That’s something I love and have a great deal of affection for when I see it through the lens. I see characters captured and presented in a way that might allow someone watching the film to have the same experience that I did. Something I get a lot out of is having an experience in a moment, and then being able to be express it and share it with an audience.

A large part [of staying focused] can be attributed to a great crew that is able to do their job and be sensitive to what we all need as creative collaborators on the set.

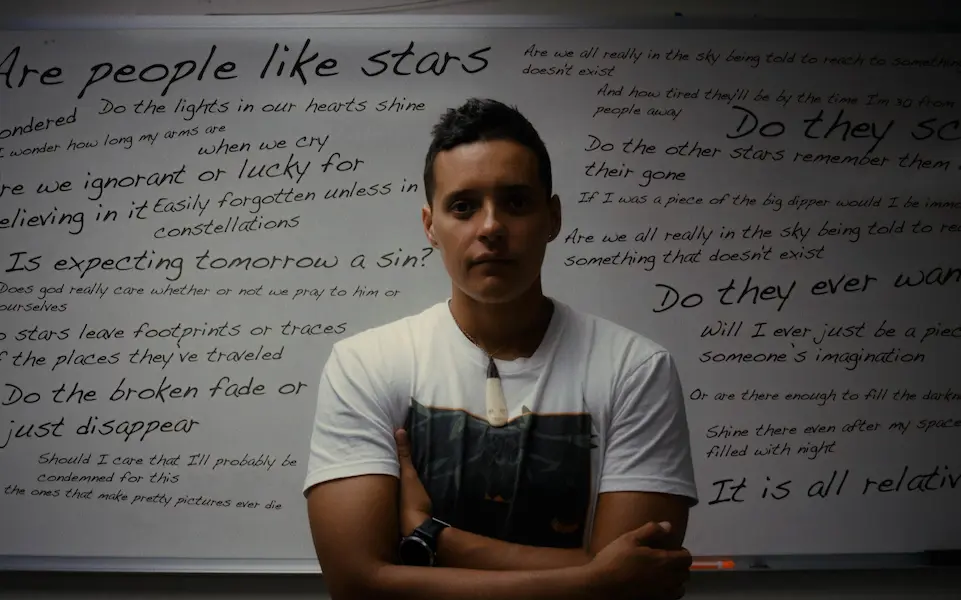

As a child, I was very watchful and quiet, and I loved new experiences with different kind of people. I lived in San Francisco in a pretty multi-cultural environment. When I went to go play soccer with people after school, this idea of cultures interacting with each other was something I was always very engaged with and really loved. And I think that continues through my adult life, and has transitioned into wanting to share those ideas with people. So, to be able to capture moments within people and characters and cultures and things like that and then present them to people is something I really love. I feel energized when those things happen.

On relying on your team to stay focused

How do you think about focus and being able to realize a vision, even with distractions?

I think a large part of that I will have to attribute to the crew. These are people that didn't get to stand up on that stage at the Oscars with us, but it should be told there's no wayI would be able to focus on the creative process if we didn't have those people making sure we were protected in that bubble, so to speak.

A large part [of staying focused] can be attributed to a great crew that is able to do their job and be sensitive to what we all need as creative collaborators on the set. The obvious stuff is just making sure you are present in that moment as an artist and you're listening and you're watching in a way that is sensitive to everyone else's creative process. But that wouldn't be able to happen without those people behind the scenes doing their work, moving the lights, making sure they're working properly, making sure the props are in place properly and the continuity of all those things.

As a cinematographer, you have to, at some point, let go of those things and allow those people to do their jobs. Some people are obsessive and they wanna meddle in everything, but I find myself trying to let those people do their jobs the way they do, in a way that allows me to focus on what I want out of the process.

But it was hard. It was challenging in many ways. We were shooting in real places with real life happening outside those doors and down the street. I think we all knew we needed to stay in that moment, and that was enabled by the crew that was around us.

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/Karen%20O%20%2B%20Danger%20Mouse%20(photo%20by%20Eliot%20Lee%20Hazel).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/Extremely%20Wicked%20Shockingly%20Evil%20and%20Vile_Sundance19_Director%20Joe%20Berlinger%20(3).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/Bedlam%2014%20(1).webp)