How Alex Prager combines new and old tech to create films that blend past and present

Published on October 24, 2019

Great films may begin with the vision of a single person, but it takes a team of skilled craftspeople to bring that vision to life.

And the bigger the team, the more complicated it can be to navigate all the decisions, iterations, and obstacles along the way.

So how do artists communicate ambitious concepts, abstract ideas, and autobiographical stories to the people who build sets, run cameras, score music, and become the characters? We asked award-winning visual artist Alex Prager to tell us how she and her team worked together to develop her new exhibition, Play the Wind.

So much of your work mixes elements of the past and the present. I’m curious if that ethos influences your technical approach as well.

It’s always been important to me to shoot as much as possible in-camera when it comes to my work, and utilize practical techniques by working with craftsmen to ensure that the worlds I’m sculpting feel tangible and real. I am always open to new technology but not if it compromises the work in any way. New technology can feel more efficient, but I’ve found that the easier or faster route is not always the best one for a project. It’s great to have both options, old and new, available to me and I do stay abreast of advances being made in both film and photography.

Do those choices ever happen at the beginning stages when the idea is still forming?

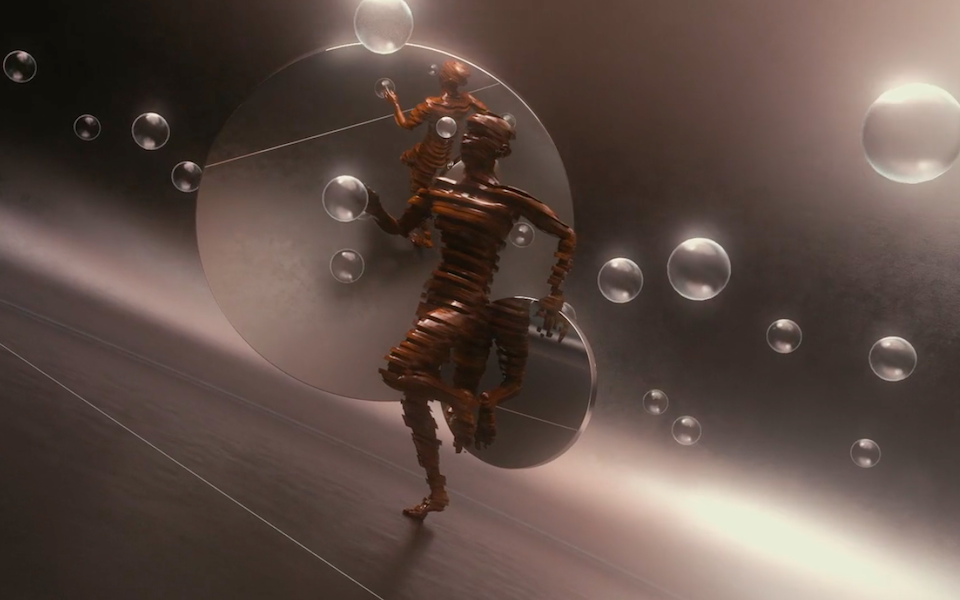

There are definitely times when I know I’m going to need the help of VFX [visual effects] to execute certain ideas. It’s really important that I have a great team working with me at the very start of a project to ensure they have everything needed to bring the footage together seamlessly with special effects and digital effects. I've been working with most of my team for years now, and value how well they can understand my vision and how to execute it.

How does that affect the process and shape the work?

Pre-production is a huge part of my work and practice. As my ideas get more complex, the production crews become more and more valuable as we put our heads together to solve that problems we encounter in that shots I’ve imagined - this all happens in pre-production. We try to anticipate everything that could go wrong on set, so by the time we get to shooting it all matches the boards we sketched out on day one. It never works out exactly like this, but that is the goal! It definitely helps to have as much as possible figured out beforehand so that we’re only dealing with limited unforeseen issues by the time we are shooting and in post. I shoot a great deal of practical effects and these things you need time for on set. The first take is rarely the one you’re going to use when it comes to a stunt or a large choreographed crowd.

You’ve said that you begin any work with one emotion (such as “Despair”). What was the emotion that was the catalyst for Play the Wind?

Despair was my foray into motion, so finding just one emotion to base the entire piece on made a lot of sense then. That was 10 years ago now. Once I began to understand the structure of narrative more, I no longer had to depend on just one emotion, so it’s a lot more multifaceted now. I made Play the Wind in response to some pivotal life moments I was going through, and this nostalgia I was feeling, but didn't trust.

I recently had my first child at the same time I was preparing for my first museum retrospective and my first monograph Silver Lake Drive. It was a big year! Nostalgia is a complicated and deceptive feeling because I wanted to move forward into all that lay ahead while simultaneously feeling myself being pulled into the past. My memories and imagination began to weave together with my feeling of longing and fight to move forward. This became the catalyst for Play the Wind.

We’ve read that collaboration played an important part in producing the set designs and props for Play the Wind. How did you work with collaborators to bring the film to life?

Play the Wind is my most autobiographical work to date. Once I knew conceptually what the work would be about, the pre-production began at an alarming rate. I had very clear ideas about what the project would be, but and I knew that it would take a large and visionary production crew to execute my ideas.

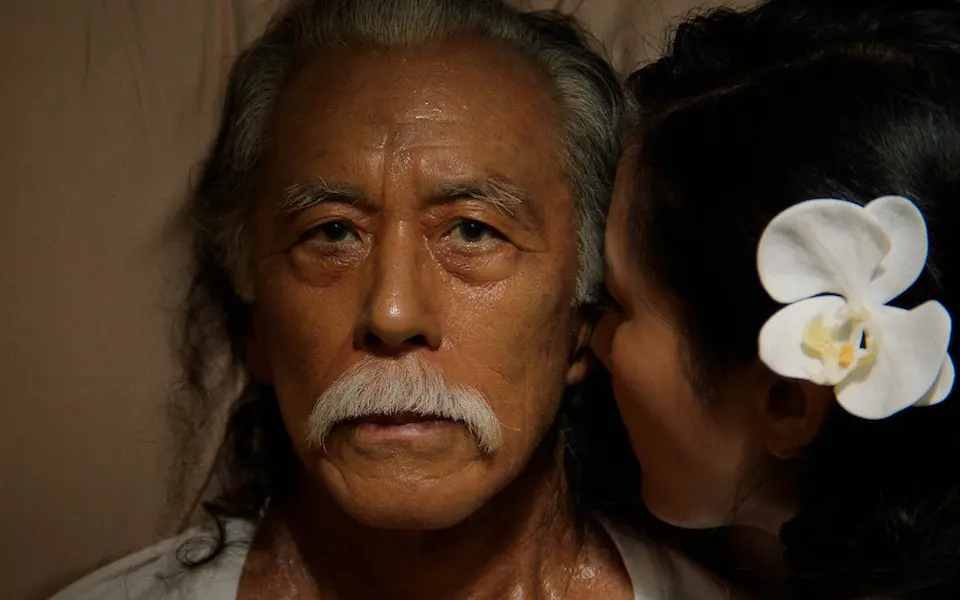

I also knew that the entire success of the film rested on the abilities of Riley Keough and Dimitri Chamblas, the two leads. I had many active conversations with them leading us to give shape to the story. They each brought their own point of view to the screen through the subtle ways in which they portray their characters' emotions. Riley is from Los Angeles and understood my sentiments about letting go of the city we both grew up in and confronting the change ahead. Dimitri comes from Paris and has only lived here for two years, so he understood his character’s journey through the city in a very unique way. They were both exceptional to work with and from the beginning and I couldn’t imagine anyone else for those roles.

I worked with my longtime cinematographer, Matty Libatique, who I knew could capture the city the way I wanted it captured—part artifice, part reality. He is such a force on set that no matter how tough things got he only ever saw opportunities in all the struggle. It was my first time shooting on location in almost eight years, so sometimes we were figuring out what Dimitir’s drive through Los Angeles in real time, which lead us to some incredible moments. Allowing ourselves that freedom is something I could only do because I had such a deep trust in my crew and actors.

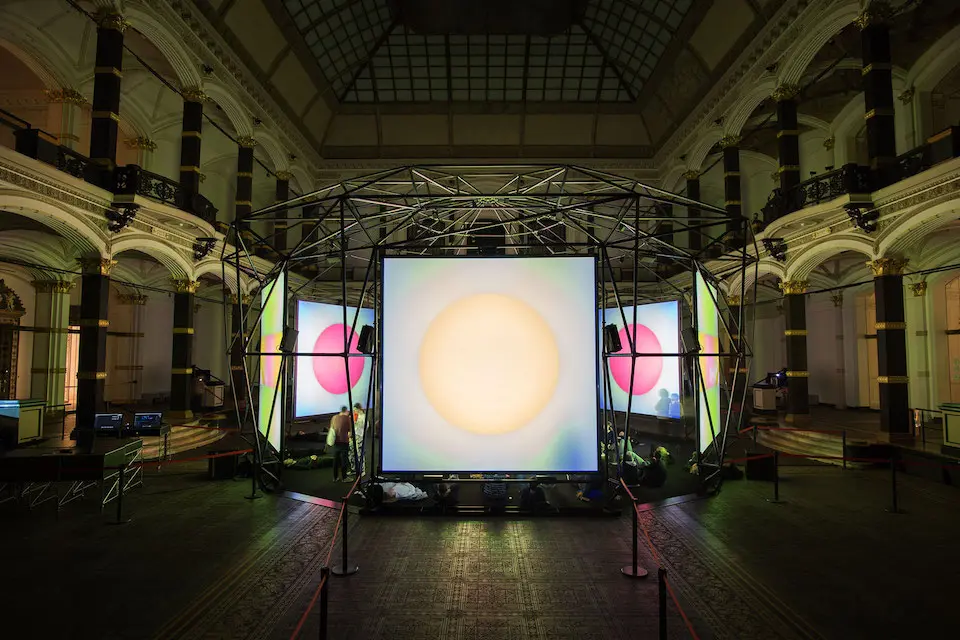

We had large surreal sets designed by Jahmin Assa and hundreds of insane, timeless costumes by Rebecca Blazak. The score by Ali Helnwein, another longtime collaborator, and sound design by Chris Scarbosio at Skywalker, were especially important to this project. Chris and I did the entire score in Atmos so you’re completely immersed in the city and the atmosphere as you watch the film in the gallery. Every little detail was shaped and manipulated in the editing room together with another one of my special longtime collaborators/magician Matt Chessé.

The VFX were done by Michael Ralla at Framestore, who went above and beyond on set and all through post. There were so many important people who had a special hand in Play the Wind. It was a very ambitious project and I didn’t quite know what I was getting into until I was already in too deep. It was because of the energy, enthusiasm and heart of my collaborators that I was able to see it through to completion.

Did any of the contributions from your collaborators shift the idea in a new direction?

One of the many things I love about film as a medium is its collaborative nature and the need to problem solve with people I trust and respect. I’ve surrounded myself with people who are exceptional in their given fields, so I’m always in conversation with them when we are bringing a story to life. Ideas put into motion can be quite a bit more complicated than if I were shooting them as photographs, so I welcomed the times where I had envisioned executing things one way but then in conversation with my crew I was convinced of another way to do it.

There is never just one way to do something so it’s always a practical choice as well as a gut decision. One example (SPOILER!!) was when we were all trying to figure out how Riley was going to walk out of the movie screen. I had imagined it as a wide match cut, which is a very simple way of achieving this idea, but unless we measured the camera’s angle precisely in the two locations— "Eden," where she is coming from, and the theater she is stepping into—than it wouldn’t cut well.

Michael at Framestore had the idea to add the projector as a close-up on Riley in the Eden location and Matty decided to basically build the theater that she could step in to from the Eden environment. That’s how we ended up with the cut we have now, which is much more interesting and complex than I’d originally conceived it.

You’ve said that your hometown, Los Angeles, is the perfect place to explore where artifice and reality meet. Could you talk about how you’ve explored that theme in Play the Wind?

Los Angeles is a city full of irony and juxtapositions, it’s incredibly photogenic but also particularly ugly. The underbelly of Los Angeles has a Wild West quality of a no rules, and you can mold the city into whatever you want to feel. I sat down at my neighborhood cafe one time, only be tapped on the shoulder by a PA telling me they’re using it as a set for a movie that day. I think of my images of Los Angeles as allegorical. The characters become part of the city’s fabric and the city becomes the main character. It’s difficult to point to where the reality ends and artifice begins.

Is that theme particular to Los Angeles or do you notice it in other places as well?

There is nowhere in the world like Los Angeles. There’s no place like home.

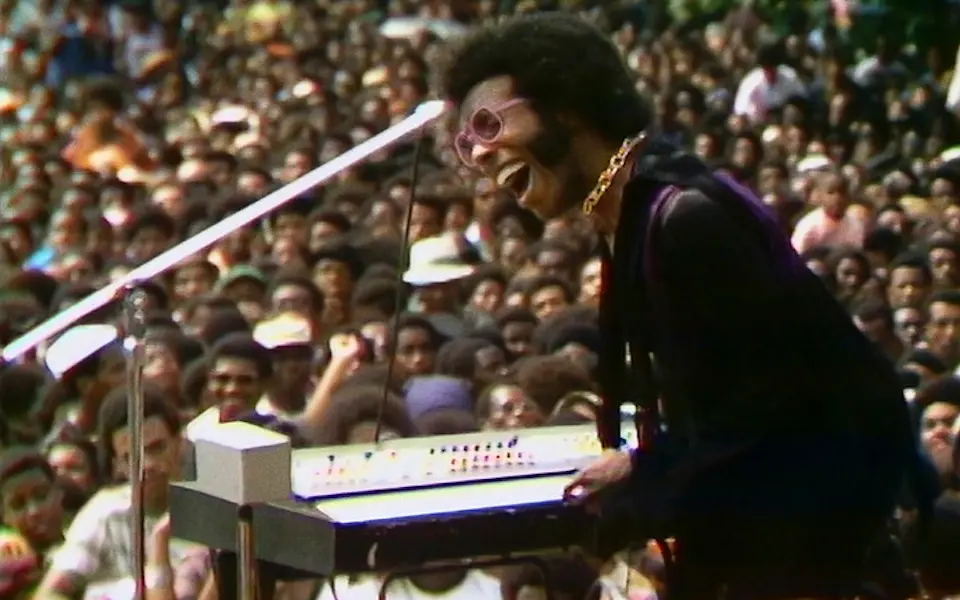

You’ve worked with Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich who scored your film La Grande Sortie and the composer Ali Helwein on many of your projects. How does music influence your creative process?

Music and sound are incredible tools to help build a narrative and express emotion. One of the things about film that always amazes me is that any single component can entirely change the direction of the story. I used to think it was just the picture that could do that. But when I began to understand editing, sound design, music…they are all equally important. Each element individually creates the story and when they are all in sync there is no more powerful way to communicate. It’s no wonder movies are so effective at connecting with the masses because they are the only genre that utilizes all mediums at once.

How did you use Dropbox to collaborate with your team in the making of Play the Wind?

Dropbox is a huge part of my studio process. It was a critical tool for me starting with pre-production to share ideas, locations, props, wardrobe, music ideas and rough cuts. My team uses it daily to collaborate with my gallery and to send photographs after we’ve scanned the negatives to my printer.

Play the Wind can be viewed at the Lehmann Maupin gallery in New York through October 26.

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/Karen%20O%20%2B%20Danger%20Mouse%20(photo%20by%20Eliot%20Lee%20Hazel).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/Extremely%20Wicked%20Shockingly%20Evil%20and%20Vile_Sundance19_Director%20Joe%20Berlinger%20(3).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/Bedlam%2014%20(1).webp)