How a Grammy-winning one-man band began collaborating with orchestras

Published on January 17, 2019

Some people seem blessed with the ability to do it all. But just because you can do a job all by yourself doesn’t mean you should. Ask Jacob Collier.

Jacob first became famous for viral videos in which he creates a self-made symphony with layered tracks. Then he won two Grammy awards for an album where he played all the instruments. But as he began thinking about his next project, Jacob decided to take an entirely different approach.

We recently chatted with Jacob and his collaborator, Ben Bloomberg, a PhD candidate in the MIT Media Lab, to find out what he learned in his evolution from one-man band to worldwide coordinator of a massively complex creative endeavor.

How did you two meet and begin working together?

Ben: I saw one of Jacob’s videos on YouTube and I thought he was totally amazing and sent him a Facebook message asking him if he needs anything and saying that I liked to build stuff. It happened to be really good timing. Jacob had just gotten this really big show and we had to figure out what to do for it, basically. Jacob had all these amazing ideas and we got to put our heads together and try to build some of that.

Is this the first time that you had reached out to a musician to collaborate?

Ben: Actually, no. I do a lot of music here at MIT. It’s the first time I reached out to a musician like Jacob.

Jacob: It was an extremely 21st century meeting… I’d spent some time putting together this video or a few videos from home in London. And Ben found a video. It was almost like a meeting of worlds. Ben had this history of working with crazy artists and figuring out how to find solutions to their crazy problems.

We actually spoke over Skype at first. It was a matter of Ben saying “What would you do if you brought this room where you made these videos and turned it into a stage?” We spoke about four hours without stopping. It was a matter of thinking “Well, I’d have these instruments, maybe just some loopers, and we’d have just vocal harmonizer machine where you can sing a note and play chords and so it sings chords and all these kinds of crazy things.”

In my experience thus far, everyone who I mentioned this to said, “Whoa, that’s crazy.” And Ben was like: “Okay: This is exactly how we’re going to achieve it. This is our criteria and we’re going to go ahead and do it like now.” So I flew to Boston. It soon became apparent that we needed a sort of international workspace. Over the last three years—from that moment of meeting for the one-man show prep to building the show for TED and making this record—everything that we’ve been using as sort of a basis of data has existed in Dropbox, which is really cool.

It’s serendipitous that we exist at this time where it’s possible to do it. These Logic sessions are no joke. It’s like 700 tracks in a session. That’s full orchestra. That’s all this midi data. That’s a bunch of plug ins.

Ben: Terabytes and terabytes.

Jacob: Yeah, literally terabytes of data. If I send a session, within 30 seconds, Ben can get it up in his machine and tweak something in the mix. Which is just absolutely stupendous. I can’t thank you enough.

"If one of us is on the road or in a plane, we can just listen within the app and then work on the scene... It’s this all-encompassing magic of Dropbox."

Could you describe the process of creating one of the more complex, layered tracks on your new record?

Jacob: Yeah, absolutely. There’s a song called “With The Love In My Heart.” It was the first single from this new album. This is my most ambitious project to date. It’s almost like five songs put together into one almighty song. This featured how many layered orchestras? Two or three orchestras playing?

Ben: Multiple passes, a complete symphony orchestra.

Jacob: Yeah. So one pass is I think 60 tracks, right?

Ben: Yeah, 60 tracks.

Jacob: Which is like 50 close mics, and then 10 room mics, all in stereo. Then obviously, we took those into Logic. I think we recorded them in Pro Tools. We imported them into Logic, which is the program I use all the time.

We stack those on top of each other. I snap them, snip them, move them around, cross faded things. Then I began to employ skullduggery on them.

Ben: And adding other instruments, too.

Jacob: Yeah. This is all before the other instruments. Just the orchestra alone is very plug-in heavy, kind of dense, rich, very much layered, very much compressed. Then we’ll take all of that spatializing that sound and getting it to feel right in the frequency. Ben engineered those sessions. Once that was done, I did record about 400 or 500 tracks on my own with the drums, guitar… over 100 tracks of just vocals. We recorded gang vocals here in Los Angeles, just a bunch of mates yelling some stuff.

Then there’s also some other sounds that are embedded. I collect sounds all over the world. Usually on my phone… whether it’s slapping a tin or stamping on a good floor or clapping in different rooms. All sorts of different things. I keep a library in Dropbox. In that library is 200 or 300 sounds and counting, just for this one album of things I’d like to use. Sometimes it’s a bird singing. Sometimes, it’s a very specific clap sound.

So, Ben obviously has access to that folder. I’ve shared that. It’s just a matter of compiling this sort of collage of all these different sections and sounds and layers in one big Logic session. Then there are multiple iterations of mixes. Ben will go do a pass and send it to me. I’ll do a pass and then Ben will go back and do more. So I’ll be dealing with sort of the dynamics and Ben is doing all the spatial stuff. After a while, we get closer and closer to a thing.

Obviously, we can access on mobile as well. So if one of us is on the road or in a plane or something, we can just listen within the app and then basically work on the scene and vice versa until we get around. So it’s this kind of all-encompassing majesty of Dropbox.

Ben: There’s a bunch of specific features in this Dropbox that we use. But one thing that we do a lot is, we’ll start a bounce. The bounces might take a while. So I can go home and I can then share it from my phone on the way home because it pops up immediately. Or we’ll be recording a big session in New York and LA. And everything we record is immediately synced to Jacob’s machine.

Jacob: At home.

Ben: So he comes home and it’s ready for him to go. And it could be hundreds of gigabytes of files. The other thing we’re getting into now is Showcase, which we use to share mixes and files, with people, make watermarked files and then share them via Showcase. We can download and see who is looking at it. It’s really handy.

"We record most of those shows and keep them in Dropbox. It’s amazing to be able to take those tracks and mix them remotely and send it to people across continents."

Are you a musician, too? Do you have experience arranging your own music?

Ben: I mostly work with other people. I studied music when I was little and so I try to approach the sounds from a musical perspective. It’s hard to say that you’re a musician when you get to work with people like Jacob. I get to have fun, but he’s the guy playing the instruments and it’s really incredible.

Jacob: Often, it’s me saying to Ben, “This is exactly what the strings are going to sound like” and I’ll play it in context or something. Then Ben will say, “Ok, so here are five examples of string sounds that you might like. Which one do you think is closest to what would work best? Something with really sparkling high and something with mellow low, some really kind of fat sounds or thin sounds, transparency, spatialized?” It’s like all these different choices. But to be honest, I’m too busy often thinking about what notes are being played and how to produce the geography of the track that I don’t think about the architecture of how that sound is going to be created. That’s where Ben really steps in and does all of his magic.

How do you choose your collaborators? You’ve worked with a lot of talented people, like Take 6 and Quincy Jones, right?

Jacob: Yeah. Quincy is kind of in charge of many things on planet Earth… So, I’ve been lucky enough to be one of their clients for about three years now, which is stupendous. Quincy is almost like a godfather to me in the sense that we hang out a lot and we talk about music a lot. He’s very open minded. I think it’s nice for me that he’s given creative license in whatever I want to do. So I’ve sort of always driven my own creative vision quite strongly and have kept charge of my ideas. Quincy has opened so many doors. It’s innumerable.

The first show that we ever did together was this show at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland, opening for these two jazz giants, Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea, two of my heroes. We opened for them in front of 4,000 people with this a crazy one-man show with this Kinect camera which captured my skeleton so I made it loop into two Jacobs, three Jacobs, four Jacobs on the stage… sometimes loopers all playing at once and harmonizing everything. It was a wild event.

And since, we’ve done 180 shows all around the world. We record most of those shows and keep them archived in Dropbox so at any moment, anyone on the team can walk right in and be like “Okay, what did that gig in Potsdam sound like? Or what did that gig in Indonesia sound like?" It’s amazing to be able to take those tracks and mix them remotely and send it to people across continents.

For this particular album, the recording of it, what Ben did is he actually, he kind of built a duplicate machine to mine at home in my studio. I would be traveling with Ben whenever he was around. We’d be traveling all around with this machine in the Dropbox. I’d walk into the studio and record the session, press save, shut my computer at home, open up and it’s completely waiting for me. That is just so sick. It’s absolutely back of the net.

When you’re choosing collaborators, are you looking for someone you communicate well with, or someone with complementary skills?

Jacob: It’s a really good question. This [new] album is one of four volumes. I’ve made four albums this year and the first one has just come out. It’s all been contained. It’s over 40 tracks over the course of this album. In total, I think it comes out to about 26 or 27 different collaborators. That includes gospel choirs and orchestras and a capella groups and legendary world musicians and pop stars and rappers, rock legends, all sorts of crazy, crazy people. I haven’t so much written a criteria about who I’m going to accept into my fold. It’s more people whose music I’ve grown up with or has absolutely hit me to the core, and just asking if they’re interested in being involved. It’s been incredible how many of them have said yes.

What I’ve found is that the long-lasting collaborators—Ben is a prime example of this—are the people who you get on with really well and who you love to spend time with.

Me and Ben have gone through a ton of really stressful situations together and also a ton of like extremely glorious, cathartic, joyous situations. So, it’s a matter of just working through those moments and having those shared experiences that also tie you together.

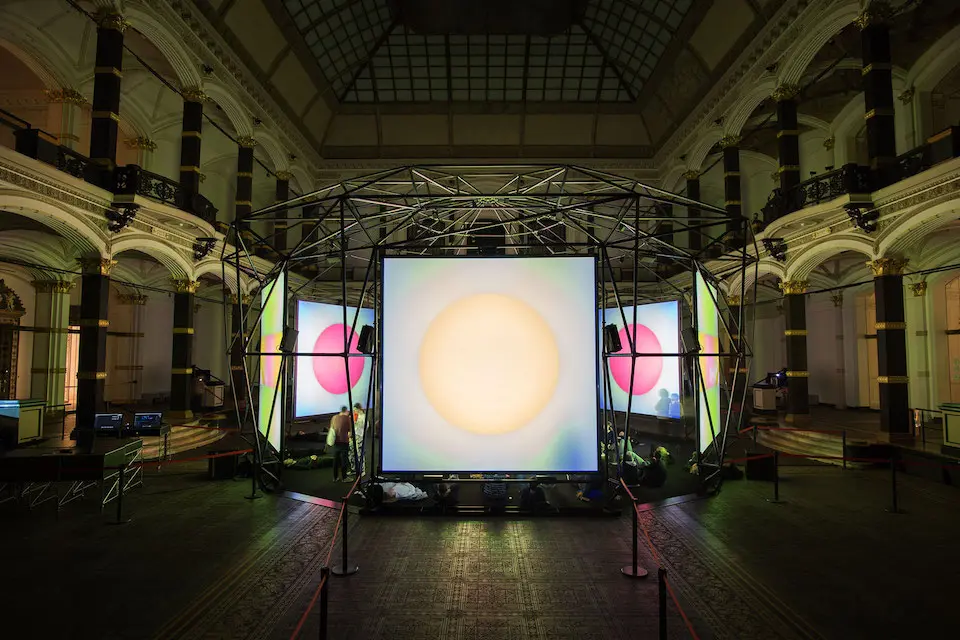

But you can never really plan those things when you go and reach out to a collaborator. When you sent me that message, I would have never imagined that it would have got to this point. Here we are in this crazy room with these six crazy pillars and 200 musicians on stage. It’s insane. But that’s the majesty of the Bloomberg.

It’s amazing to grow my imagination alongside someone whose imagination has similar aesthetics but different skills. I bring a lot of the storytelling and creative elements. Then Ben brings solutions to those things from a technical perspective. But each of us also has a very clear understanding of the other person’s world. I’ve sort of dabbled in technology throughout my life and obviously being a producer and video editor. I’ve got my hands fairly filthy in things like clicking and dragging things. Ben obviously is all-time master of those things, but also has an extremely emotional understanding of art and music and storytelling. So we’re lucky to have each other.

“I’m learning so much from the process of working with other people. I’m learning about myself. I’m learning about the language of music but also what it means to be a human being and what it means to be under pressure and what it means to rely on yourself and trust yourself and what it means to trust others.”

You’re famous for being able to do densely layered arrangements all by yourself. So when you’re working with other people, what is it about collaboration that adds to your experience?

Jacob: Well, I made this album called In My Room completely on my own and it was almost like an experiment. It was like, “What if I give myself three months to write songs, arrange songs, play every instrument, mix every element and do it all alone?” I did that and I toured the world as one man. It’s that inevitable step forward towards bringing the feeling of that music into other people’s hands.

I mean, it’s the difference between one life and four lives on stage, or in this case, one and 200. You can’t do this as one person.

I’ve played stages that are as big as this and crowds a lot bigger than this as one person.But it’s difficult to fill the room in the way that this is going to fill the room tomorrow night just because it’s 200 people bringing their entire universe to play your music.

Each of us brings our own language and sensibility and aesthetic and energy and passion. For me… it’s like an experiment. It’s like, “What happens if I reach out to every one of my musical heroes and make four albums in a year?” I’m learning so much from the process of working with other people. I’m learning about myself.

I’m definitely learning about other people and learning about the language of music but also what it means to be a human being and what it means to be under pressure and what it means to rely on yourself and trust yourself and what it means to trust others. I think there’s that amazing feeling that I’m having this year that I haven’t really ever had before in this way which is: “You do your thing because I know it will be better than what I can do. I know it will add to the process in a way that I’m unable to.”

I have as much awareness as I have. My world is always as big as my world is in my own eyes. It’s amazing to bring completely new energy and to welcome that as a force. It feels like the right time in my life to open that up. And I’m opening it up in a very extreme way I suppose. “Let’s get dirty together. Let’s tell some stories.” The vision of the project is my own and the arrangements are my own.

The conception of the ideas has come from me. But I think what’s amazingly exciting is that the idea and the album, the sound of the album is so much bigger than I could ever have imagined it alone just because all of the different human beings being a part of it have added their own glory.

Did any tracks take a turn because of someone else’s input? Does having so many options make the decision-making process challenging?

Jacob: Yeah. I mean it’s absolutely infinite. You have to just trust your gut feeling. And there are sometimes where your gut feeling has to collaborate or communicate with somebody else’s and one example of that was when I went to Casablanca in Morocco to record a song called Everlasting Motion with my good friend Hamid El Kasri… one of the greatest living musicians. Working with him was a trip because he doesn’t really listen to any western music, doesn’t speak English, has no particular idea of traditional harmony but he has this massive working experience.

For me it was a matter of bringing my creative affinity… and realizing that in order for this to work the best it possibly can, I have to meet you in the middle. So, he’d say this works or this doesn’t work or he’d imply this works or this doesn’t work. That would make the song take this kind of diversion. Then obviously afterwards, together we’d sit and we’d find ways to get his sounds to fit and sit perfectly within my sound world and the thing to work as a whole. That’s where it gets really exciting.

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/Karen%20O%20%2B%20Danger%20Mouse%20(photo%20by%20Eliot%20Lee%20Hazel).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/Extremely%20Wicked%20Shockingly%20Evil%20and%20Vile_Sundance19_Director%20Joe%20Berlinger%20(3).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/Bedlam%2014%20(1).webp)