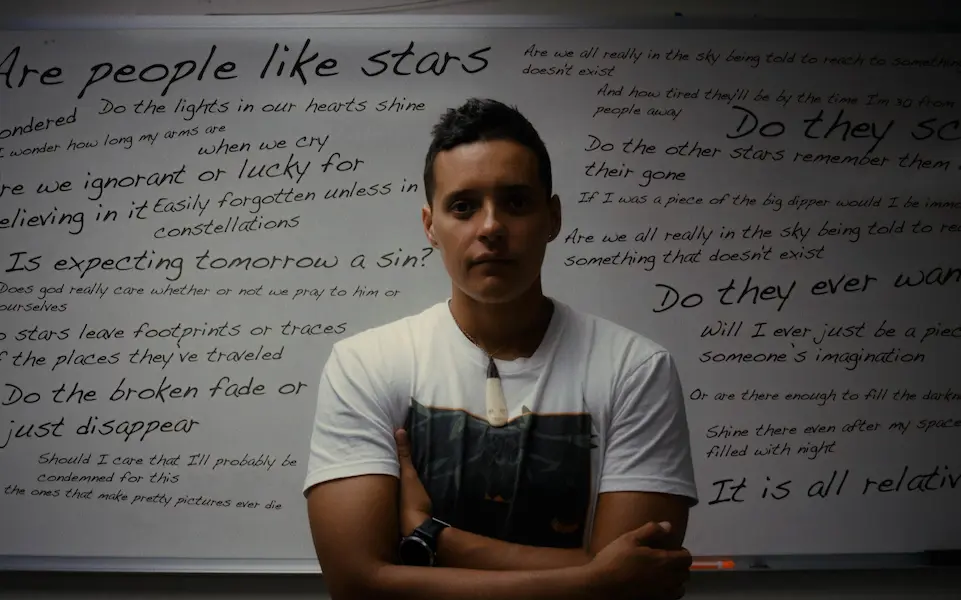

Holly Herndon on merging the worlds of music and AI

Published on October 10, 2019

Music and technology have been bandmates for years. With every invention—from multi-track recording to synthesizers to live-looping—musicians have been able to tap into new tools that stretch the limits of what’s possible in the studio and on stage.

Now, with the advent of artificial intelligence, there are new boundaries to explore—and Holly Herndon is a pioneer at the crossroads of AI and song.

Born and raised in Tennessee, Holly is a composer, musician, sound artist, and Doctor of Musical Arts from Stanford, who moved to Berlin as a teenager and quickly became immersed in the city’s dance and techno scene.

On her first album, Movement, she created custom instruments and vocal processes with the visual programming language Max/MSP. On her album, Platform, she included the song "Lonely at the Top," which was designed to trigger autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR).

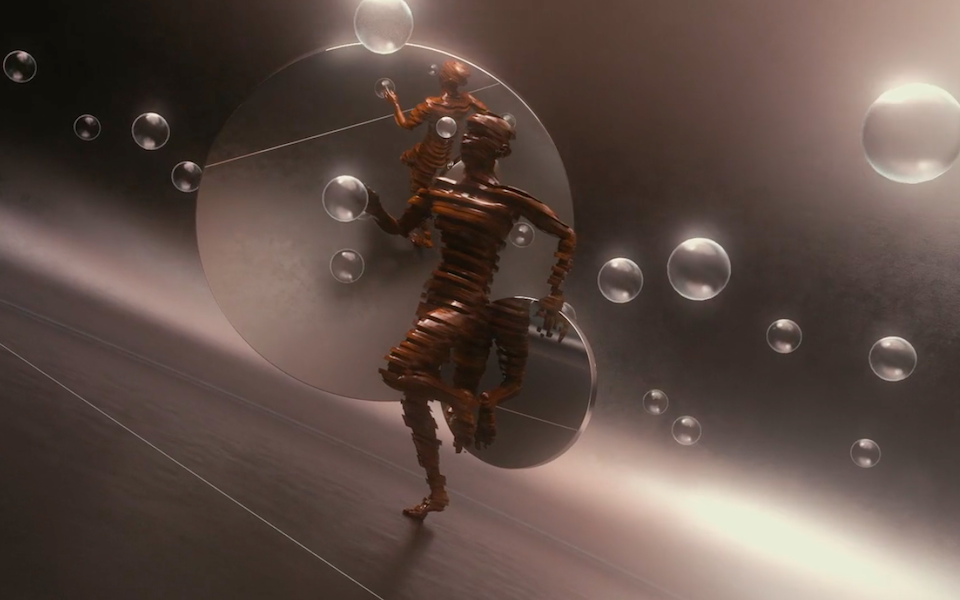

On Holly’s new album, PROTO, she includes two tracks that demonstrate the process of training her AI baby, “Spawn.” We spoke with Holly to learn how she balances her need for time alone in the studio with time interacting with her audience and other artists, and what she sees in the future of AI/human collaboration.

"I don't think I ever fully comprehended how powerful the computer could be expressively, even gesturally."

When did you first discover your love of music?

I started singing in the church. A lot of my musical life was in a religious setting, but I was also very active in school choirs. When I was really young, I used to make cut up tape collages with my girlfriend, and we called it our radio show. It obviously wasn't a radio show because it wasn't broadcast anywhere. But we made all of these fake radio shows from a very young age. It's just something I've always been drawn to.

When did you start composing and writing songs? What first inspired you to go beyond learning the songs that you sang in church and choir?

I was making up my own songs when I was doing this little fake radio show. Because we would do news programs, then that would be interspersed with musical content. So I was ad libbing country songs, which would be really hilarious to listen to now, I actually don't know where those tapes are.

When I was an undergraduate, I took some electronic music classes. I was learning how to use modular synthesizers, digital synthesizers. Then when I moved to Berlin, I started playing in bands, and making music with other people. It started with more hardware, then I eventually moved on to software.

That's when I decided to go to Mills because I wanted to increase my skill level, and learn how to program and use the computer more effectively. I wasn't really using the computer that much until I got to Mills. There was a period of time where I was taking orchestral contra bass lessons. That was just a weird tangent. I was never very good at it. But I felt this desire for a huge tactile instrument. It’s insane because my teacher was [a few] subway lines away from me so I had to change train platforms with this giant, very inconvenient instrument—the opposite of what I became. But maybe that's what did it to me—I was just like, “F this! Give me a computer!”

When I went to Mills, I still had my contra bass with me. I was still taking some lessons, and I don't think I ever fully comprehended how powerful the computer could be expressively, even gesturally. Once I realized that, it became a primary focus for everything.

"So much stuff happens online... But in some ways, people try to replace the physical part with that, and it's not the same as being there and participating."

Do you remember a moment where you thought, “Electronic music is my genre. This is where I want to dive deeply?”

I was first exposed to electronic music the first time I was an exchange student in Berlin. The first time I was an exchange student for two weeks. The second time I went back for senior year of high school.

So you didn't move to Berlin specifically for the music scene? You found the music scene after you moved to Berlin?

Right. When I was a teenager growing up in East Tennessee, I didn't know about a music scene. Growing up in a fairly conservative environment and then going to a city like Berlin where teenagers are given much more autonomy and much more freedom from a young age, that was also an unusual arrangement because I was placed with a Polish family in Berlin. They were so awesome.

We would go to these markets and they were selling these insane euro dance compilations. It sounds like if you went to a Tomorrow Land or something. I was just like, “Whoa, what is this music?” Everything was synthetic. The voices are super processed. I was like, “This is insane alien music.” It's also designed for peak euphoria. So I saw some similarities in the emotional aspect of it with religious ceremony. That was my early exposure to electronic music.

Then when I went back to stay with a family for a year, I started clubbing for the first time and you know, I didn't know anything about about club music. But there was a teenager my age in the family and we were really close. So we would just go exploring on the weekend. There was this one iconic Drum and Bass club in Berlin. We would go there and dance and be nerds in the corner, trying to figure out what was going on. I guess Berlin was my portal to electronic music.

How did you find your first bandmates?

Just by going and being involved. I was going to clubs a lot. You just get to know everyone, then you have ideas and those are your friends. Then you try out those ideas. It's just about showing up.

Maybe that's the difference today with a lot of young people. It especially depends on where you are geographically. So much stuff happens online, which is really cool. It's amazing that people don't feel so alienated. I definitely felt alienated during high school in Tennessee, because I wasn't spending a lot of time online at that time. I think the Internet has provided a really amazing outlet for people in that way. But in some ways, people try to replace the physical part with that, and it's just not the same as being there and participating.

How has technology changed the way you think about collaboration?

I think it depends on the project. For my first album, Movement, that was more me being a reclusive freak. That one was more of a solitary experience. Then with Platform, that was more collaborative, and most of that was online. Then with PROTO, it's been very much in person and that was something I was craving—this real-time music thing with people.

One of the reasons why I wanted to start an ensemble and start singing with people again is because I was lonely in the studio. But the irony of it is, even though I spent tons of hours singing with people, the more files you record, the more hours you have to spend in the studio by yourself editing them. So you never really get away from that. That's also fine. I really like alone time in the studio. I'm not the kind of person who necessarily will just roll up and jam with someone. I like to work things out on my own in a lot of ways, but I also like generating material with people. I like doing both parts of the process.

Do you consider working with AI a collaboration?

I consider Spawn as a performer, as an ensemble member. So I would say that I collaborated with a human and an inhuman ensemble. I certainly consider those collaborations. When you write a score, then somebody reads it, human or inhuman, there's an interpretation happening there. Things always come out slightly different than when you imagined it. That's how I've used Spawn as a performer. It's collaborative in that sense.

Do you have any plans to compose using AI?

There is some improvisation that happens when Spawn interprets something that I write. It's not a binary between composing and performing. There is an entire gray area of interpretation and the improvisation. However, I prefer to stay on the end of maintaining the composition. There are many reasons for that. Anytime you're working with a machine learning system, and you're teaching that machine learning system to compose in the style of the canon that you provide, you have two choices. You can either provide a canon—which is a collection of other people's work—or you can provide a canon of your own work, or a combination of those things.

I have a problem with all of those solutions. If I provide a canon of someone else's work, then I am trying to recreate someone else's style. I don't think it's necessary for me to try to recreate an existing composer’s style. The composer already existed and came up with that style as a response to the material conditions around them. That was their emotional response. It’s totally unnecessary for me to do that. If I use my own personal canon as training data, then I'm freezing myself in time and not allowing myself to compositionally move forward. So it creates a cul-de-sac where, the composition will be limited to what I have done before, but doesn't really break out of that.

I like to maintain that autonomy and that agency of being able to grow and change my aesthetic and change my form as I change as a human being experiencing the world around me on a daily basis.

Could you describe your process for making AI voices sound more human?

When I started working with the laptop at Mills, the conversation at the time was in an academic and very improv-heavy environment. There was this conversation that was happening. questioning whether or not laptop music could be considered a performative instrument, whether it could be a a valid performance. It might seem a little dated now, because everyone is performing with laptops, but at that time, that was a conversation that was happening. So my project there was trying to figure out how to make laptop music feel more embodied for the audience.

My solution to that was to digitally process the human voice—the human voice being something that our ears are incredibly attuned to the frequency range. It's an evolutionary thing. We all are very attuned to the human voice. Most of us have access to our own voice and know what it's like to vocalize. It's a relatable gesture. So by digitally processing that in real time through a laptop, the audience could recognize the performer and what was happening, while still being faced with a maybe alien, or extremely digitally manipulated sound through the speaker system.

So that’s where it all started, this obsession with the human voice and electronics. It's just been a building process from there—navigating and understanding that intimate relationship that I have with my laptop, how that's probably metabolized by the internet that it's connected to and the social media dynamics that are connected to my primary instrument. Working with artificial intelligence is building on that foundational art practice that started years ago.

"My dream is that technology should allow us to be more human together rather than alienating us further. "

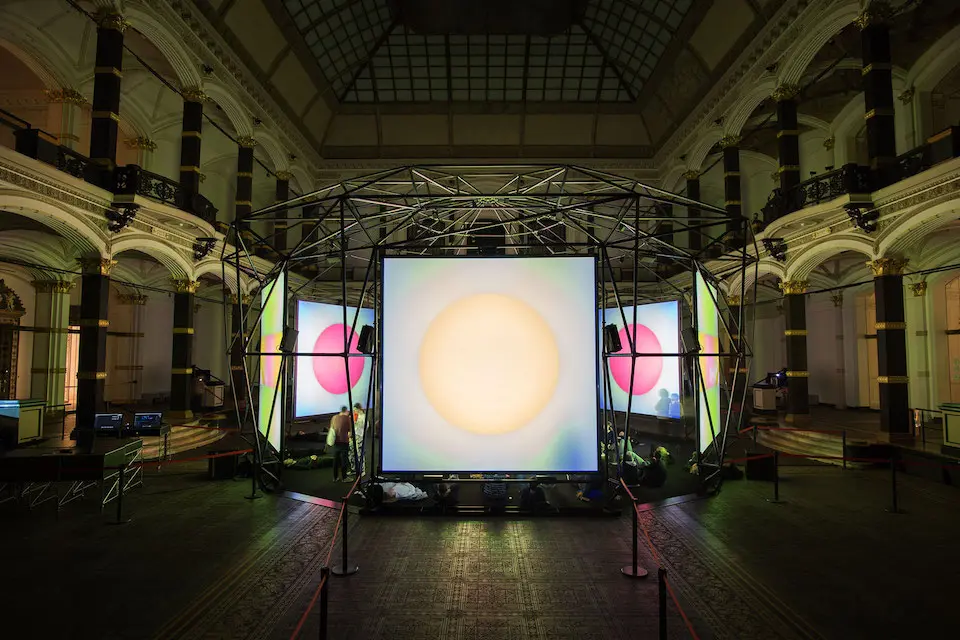

I understand you invite audience members to engage with the material and experience it in a direct way. Can you describe what that looks like?

I should mention some of the collaborators. My partner Mat Dryhurst, he's a huge part of the process. We write and produce together. We also train Spawn together. Jules Lovelace helped us by doing the hard work of reading through all of the papers and helping us figure out which machine learning architectures would work best, and spending hours with us training Spawn.

We started transforming my voice and then Mat's voice and then Jules, and then we open up to the ensemble. There's a group of about 10 people in Berlin who are all amazing musicians in their own right. It requires a lot of trust and an experimentation with material. It was a very collaborative project. An act of collective intelligence.

We decided we try to model an audience voice. So we did a few public training ceremonies in 2018, almost a live theater performance where the ensemble was leading the audience through these training exercises that we would record and then we use this as training canon.

We're doing that as we tour as well. Different ensemble members will lead in a call and response song that we've been recording. The goal is to be able to create an audience voice model for each unique audience. It was a way for people to tap into some of that euphoria I was mentioning before. There's just something really beautiful about singing in public. Singing community is part of our evolutionary history. It taps into that in a really beautiful way.

What sort of improvements in the technology are you anticipating in the years ahead?

I guess processing will get a lot faster. We will probably be able to do more real-time stuff. Right now, there's quite a latency for some of the real-time systems. We still have maybe two seconds delay on some of the stuff that we're doing. So I'm guessing that will shorten some of the rendering times. I still think we're in the early days of how to deal with automation in musical performance.

So many electronic music festivals I go to, the human has been automated off stage. It's more about the video performance. Or the mechanical lights become the dancers or performers. A lot of that sounds like economics—it's just cheaper to do that. But that's one reason why, on this project, we wanted to reinstate the human form onto the stage and put that front and center and figure out, “If something becomes automated, what does that free up for us to do as humans?” My dream is that technology should allow us to be more human together rather than alienating us further.

So many of the products and so many of the habits that we have with our technology pushed us towards alienation. But really, it could free us up to be more human and more emotional together by taking some of the work, essentially.

How do you use Dropbox in your creative process?

You know, Jules doesn't live with us and Spawn lives with us. So we use Dropbox to share files, organize and share favorite outputs. I also use Dropbox quite extensively for admin. That's such a huge part of a creative process as well as just having a shared archive. My management teams in New York, we have to be able to share budgets and invoices and all those things. So we use Dropbox for all of that stuff.

Holly is our second Dropbox Brand Ambassador. We invited her to join our community of Ambassadors because of her pioneering vision and expert ability to use Dropbox to collaborate with her team and create something completely original. To learn more about Holly, and hear her new album, check out hollyherndon.com

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/Karen%20O%20%2B%20Danger%20Mouse%20(photo%20by%20Eliot%20Lee%20Hazel).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/Extremely%20Wicked%20Shockingly%20Evil%20and%20Vile_Sundance19_Director%20Joe%20Berlinger%20(3).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/Bedlam%2014%20(1).webp)