This innovative company is addressing the future of clean water access

Published on November 03, 2023

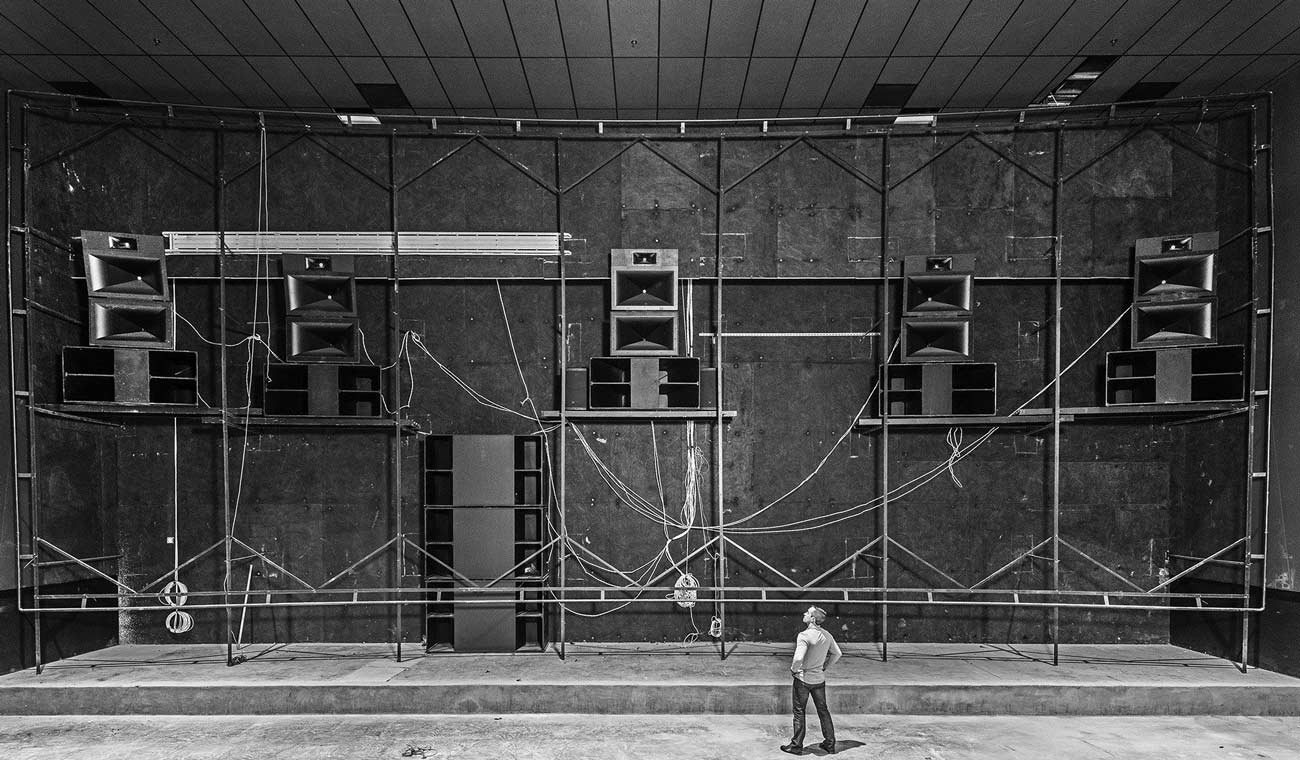

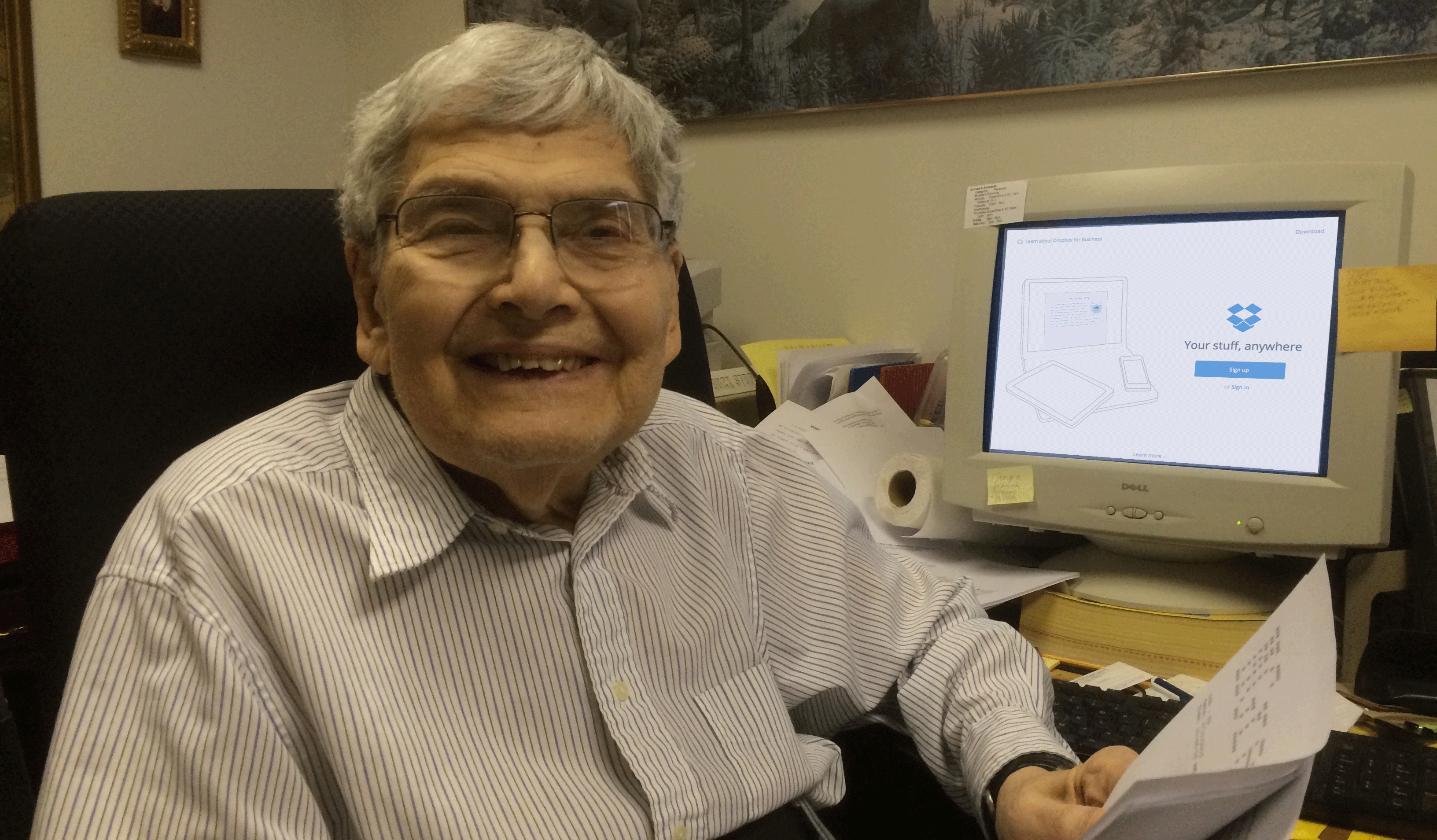

“This is where I do all the crazy, mad scientist stuff.”

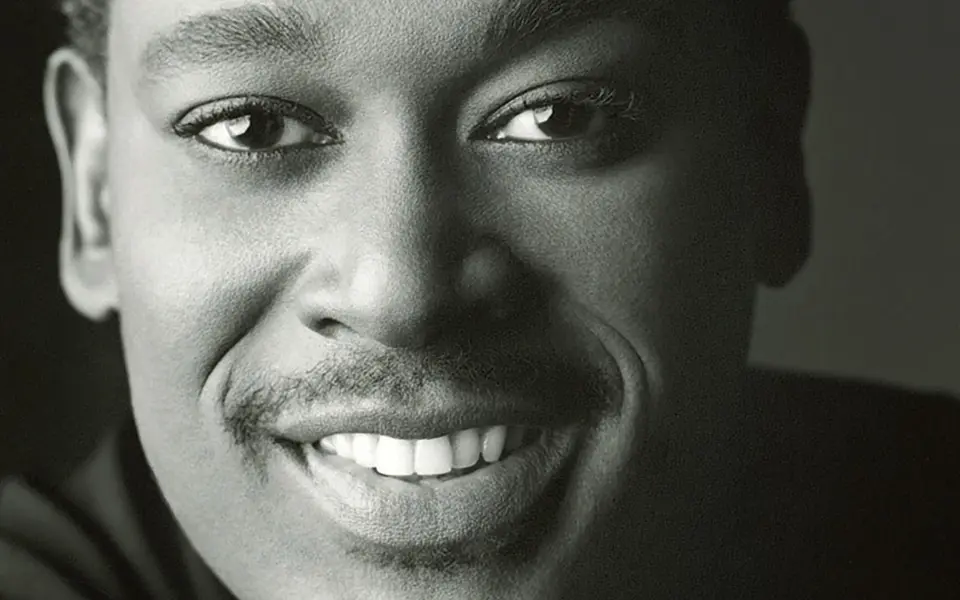

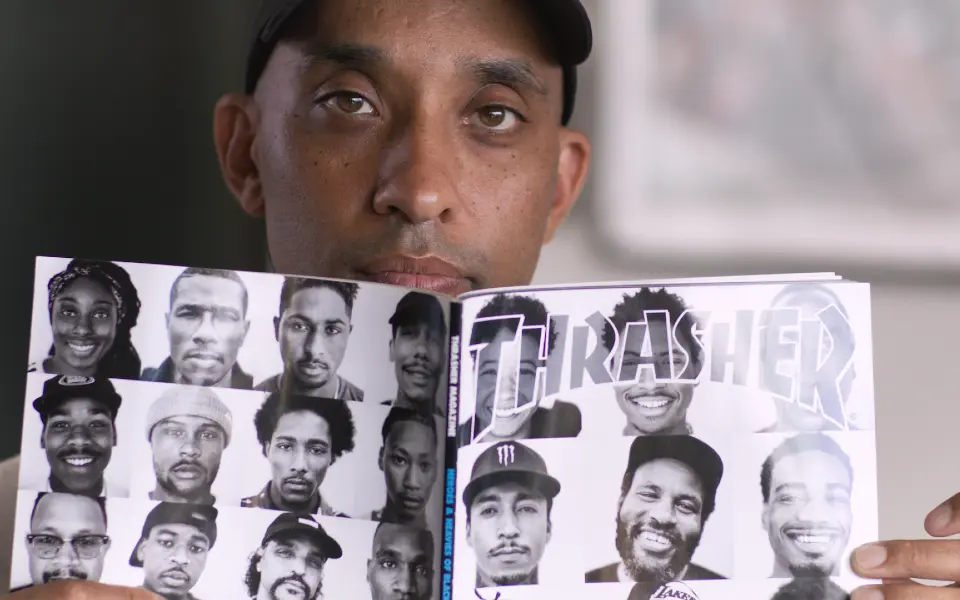

Reuben Vollmer moves out of his camera’s path to show me what’s directly behind him. His Venice Beach, California home office is not the stuff of Dr. Frankenstein’s or Dexter’s laboratories, nor did the haunting notes of a theremin suddenly appear, but I see what he means. Any available space is covered with parts, papers, and prototypes. He then directs my attention to the reason why I called: Spout, the machine he’s invented in the hopes it will “become the third source of water for humanity.”

Spout is a slim, 3D-printed pitcher that can make 2.5 gallons of filtered, alkaline water from thin air. It is currently the smallest, quietest, and most affordable atmospheric water generator around. (While $599 isn’t cheap, it’s closest competitors are four to six times more expensive.)

The technology behind it has been around since time immemorial, but is much more accessible than using nets and cisterns to collect water from dew and fog. With Spout, you just plug the pitcher in and let nature do what it’s already and always doing.

“I just got super excited by this ability,” he says. “People don’t like plastic bottles, and 40% of Americans don’t trust tap water. We don’t have to rely on petroleum for plastic bottles that you use for 60 seconds and then the bottle lasts for 500 years."

It’s been an easy sell: Five months after Spout officially launched in May this year, the company has had almost $1 million in preorders. A water pitcher that makes its own water? The need for such a product is obvious. UNESCO released a report in March declaring that humanity is at “imminent risk” of a global water crisis. Once you read the report’s findings—that in 2020, 26% of the global population didn’t have safe drinking water, that “between 2-3 billion people experience water shortages for at least one month per year”—it’s hard not to feel like we’re already knee-deep in one. From Jakarta, Indonesia to Jackson, Mississippi, people are drinking unsafe water due to poor infrastructure, municipal malfeasance, climate change, or all of the above.

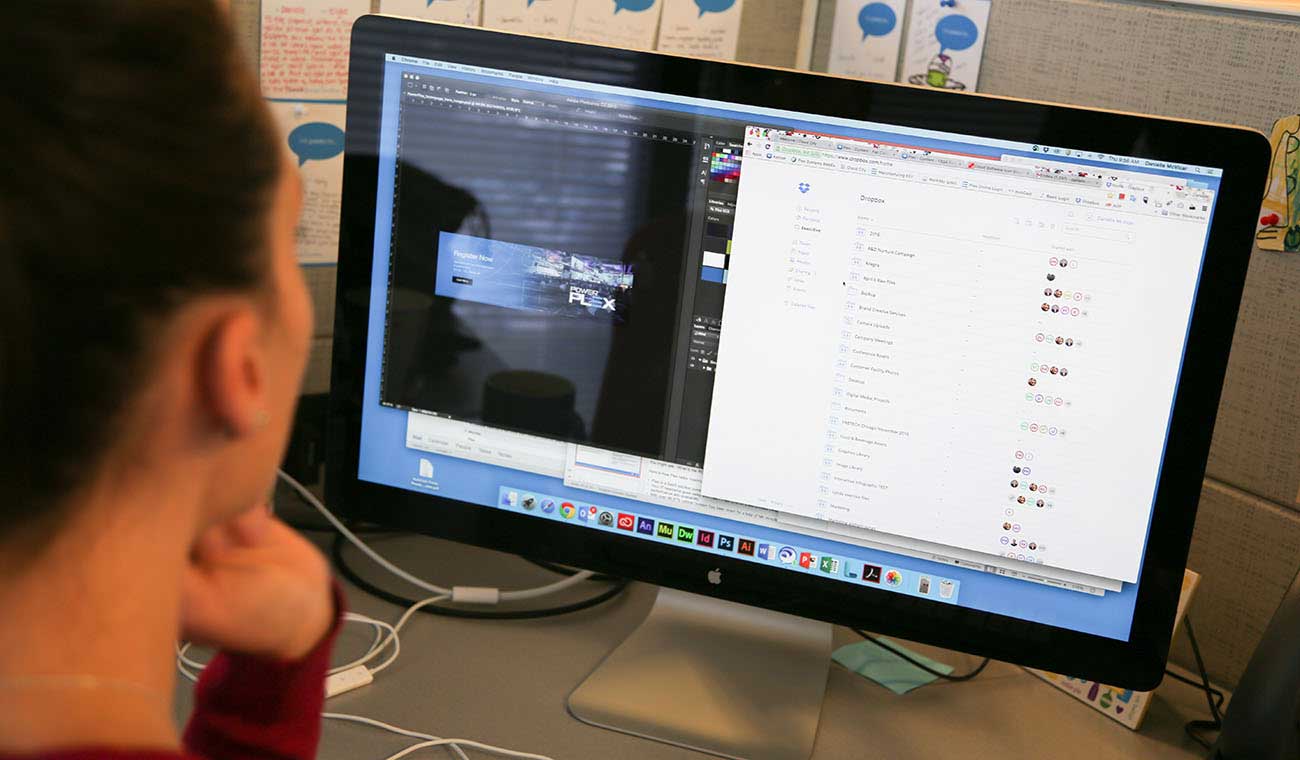

With stakes so high, Vollmer, his business partner Tyler Breton, and their team are determined to make Spout as ubiquitous as faucets and wells. Spread throughout the greater Los Angeles area, Seattle, and San Francisco, the team chose to congregate in Dropbox-powered products to not only stay organized but also pitch investors through Docsend and coordinate contracts through Dropbox Sign.

“We have a spreadsheet that has every part name and then a Dropbox link to download that part, 3D print it, and make the machines,” Vollmer adds. “[Dropbox is] critical to keeping our company organized.”

And that organization helps Spout stay focused on what Vollmer calls their “North Star”: “We’re just trying to make this thing available to as many people as possible,” he explains.

But it has taken Vollmer years of iterating, collaborating, failing, and starting over again, to get to where he is today.

Jumping into the deep end

Vollmer has spent the last decade seeing the human cost of the water crisis. Back in 2014, he was a creative technologist solving problems for Fortune 500 companies and a son worried about his family’s farm. California was experiencing its worst drought in 1,200 years when his parents got a letter from the state effectively saying, “’Hey, don’t count on having water,’” Vollmer says now.

His folks had 14 acres of olive trees and they were supposed to be getting ready for their first harvest. Where would they get water if the government decided to turn off the hose?

The lack of answers got to Vollmer, so he put himself to work. After all, he was a self-taught engineer. He did rapid prototyping for a living. Maybe he could rig up a solution.

Inspiration struck during an early morning walk with his dog.

“I noticed the dew on a grassy field and thought, There’s water coming from the air? Just naturally? Why can’t we, like, tap into that?”

With that direction, Vollmer created the first prototype using tin foil and panes of glass to collect condensation. After years of research and tinkering, he had built a machine that could produce 10 gallons of fresh water using humidity and electricity. As the water flowed, Vollmer realized he could help more than just his parents and other drought-stricken farmers in California.

“I noticed the dew on a grassy field and thought, There’s water coming from the air? Just naturally? Why can’t we, like, tap into that ?”

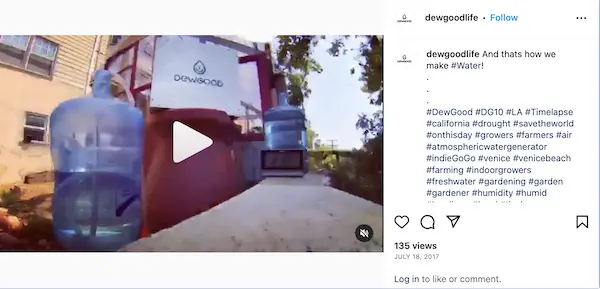

With that “eureka!” in hand, Vollmer founded a company called DewGood. The machine—now named DG-10—would be its first product, the first of many to “mine water from air.” In 2017, he launched an Indiegogo campaign for the $50,000 needed to finalize production and scale.

“It seems really simple to me,” he says now. “I’m very delusional sometimes, but I’m like, I just think everybody would want this.”

Sink or swim

But reader, everybody did not, in fact, want it. For all of DG-10’s perks, there was a lot working against it. For starters, the 20-inch cube weighed about 100 pounds, and the water came out of a long, clear hose. Even if you could get past those aesthetic concerns, the price—$1,499—was ultimately a dealbreaker for most people.

DewGood didn’t meet their goal, and the experience left Vollmer feeling defeated for a year. But the negative response on Indiegogo and Reddit didn’t reflect reality: People experiencing water scarcity wanted this technology.

Vollmer saw that firsthand when he attended the Flint Water Festival. The people of Flint, Michigan intimately understood the need for DewGood—their tap water has been contaminated with lead and the bacteria that causes Legionnaire’s disease since 2014. (And no, as of publishing, Flint still doesn’t have clean water.) Vollmer spoke to a mother with a devastating story: She lost her two children to lead poisoning caused by drinking the city’s water.

“When you give somebody a glass of water, there’s an intention there of wanting that person to be healthy and to grow strong, especially if you’re a mother,” he says. “To think that people aren’t doing that but poisoning each other instead of giving them life is such a profound tragedy.

“That was the moment for me where I was like, I’m never giving up on this.”

DewGood took Vollmer around the world and every encounter helped him think of a new approach to the product. Its latest evolution fell into place when he met his business partner Tyler Breton in 2018. Vollmer was supposed to be vetting Breton as a potential CEO for a friend’s company, but Breton wanted to know more about DewGood. After borrowing a machine, he was sold.

“As soon as I tried the prototype for the first time, its untapped possibilities struck me,” Breton explained via email. “To transition from an interesting concept to a market-ready item, it was clear to me that we needed to miniaturize the device, mitigate its noise level, and make it more economically accessible.”

Water, water everywhere

The pair took DewGood’s core mission—getting fresh water to the masses—and made it easier to understand by addressing those stumbling blocks Breton had noticed.

This time, instead of crowdfunding, Vollmer and Breton went the VC route. The pair sold investors on a new story (and a more aesthetically pleasing prototype sans hose). Now called Spout, they were a home-tech company producing pure, self-generating water. They had Spout’s water tested, and found that it was purer than tap, bottled water, and water delivery. Given the current climate and water crises, who wouldn’t want that?

This time, dear reader, people did, in fact, want that. Vollmer and Breton sent pitch decks to investors using Dropbox DocSend. Thanks to DocSend’s document-tracking analytics, it became a vital tool for vetting investors.

“I can actually see who’s spending time on the pages and going through our deck thoroughly,” Vollmer says. “It really means a lot to me when I can see that an investor keeps coming back to our deck, and they keep asking better and better questions.

“Right now our main goal is to validate our product,” he continues. “So all the feedback that we get from giving people documents, and actually seeing how they’re interacting with it, is incredibly valuable.”

The new marketing-and-design focus worked, and Spout was able to secure funding from several investors. Vollmer and Breton then tapped Bould Design (the industrial designers behind the Nest thermostat) to take their prototype from Brita Filter meets dorm laundry basket to the sleek countertop appliance it is today.

With a successful launch behind them, Vollmer is now focused on finding ways to make Spout more affordable without compromising on the water’s quality. Ensuring both is essential for Spout to become humanity’s third water source, he says.

“That's an insane thing to want to do,” he allows, “but it's our North Star. And every decision we make in the company, we check, Is this leading toward that North Star or away from it?”

It’s probably not a coincidence that Vollmer chose the North Star as Spout’s guiding principle. (It even appears in the company’s logo.) After all, when you look up at the night sky, you can use the stars that make up the Big Dipper to find it.

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(2).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/1200x628%20(5).webp)