How AI and new tech are transforming the design process at Atelier Brückner

Published on July 25, 2023

In the field of narrative design, a building is never just a space. For ATELIER BRÜCKNER, it’s where a story begins.

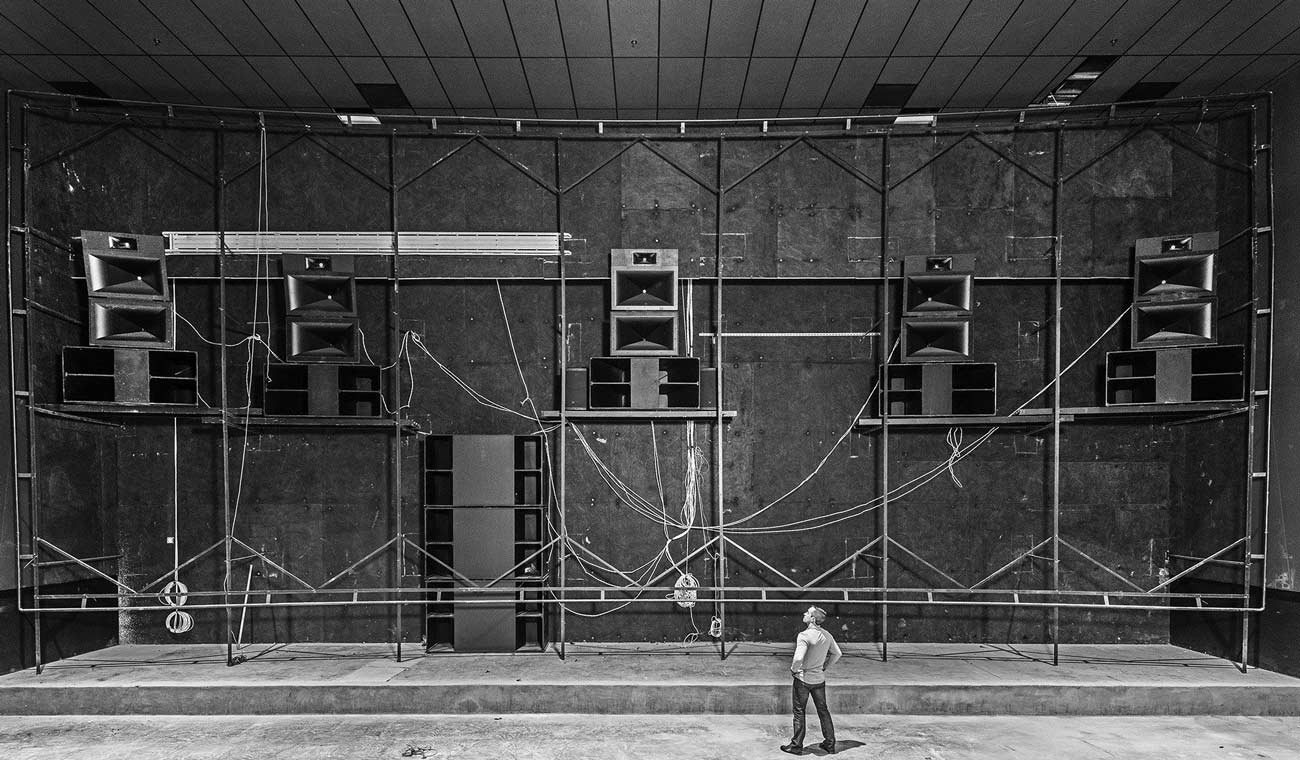

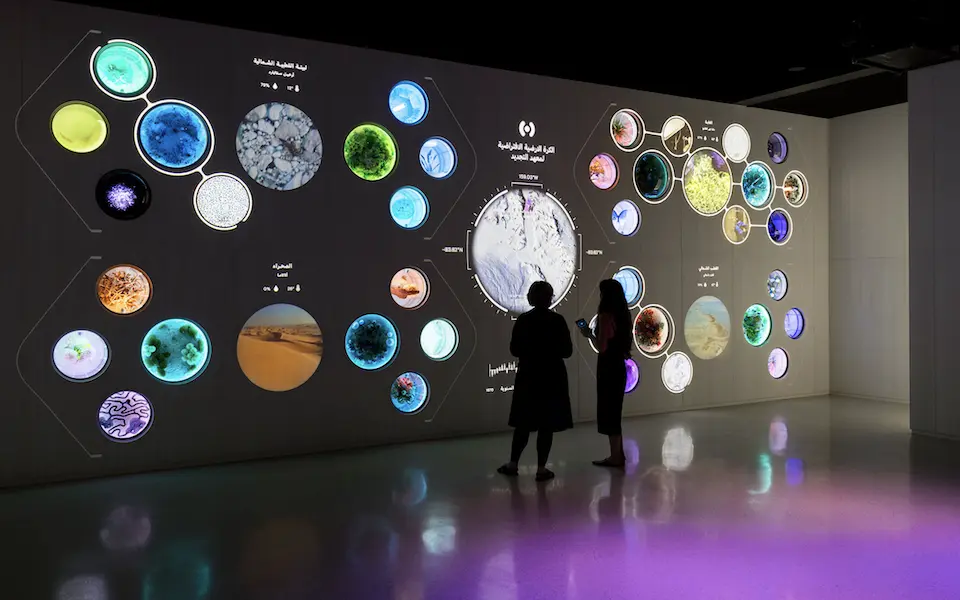

Based in Stuttgart, Germany, the design firm creates massively immersive installations for clients around the globe, including BMW in Munich, The Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, and the Museum of the Future in Dubai, where they conjured a mind-expanding exhibit with the help of consultants from NASA.

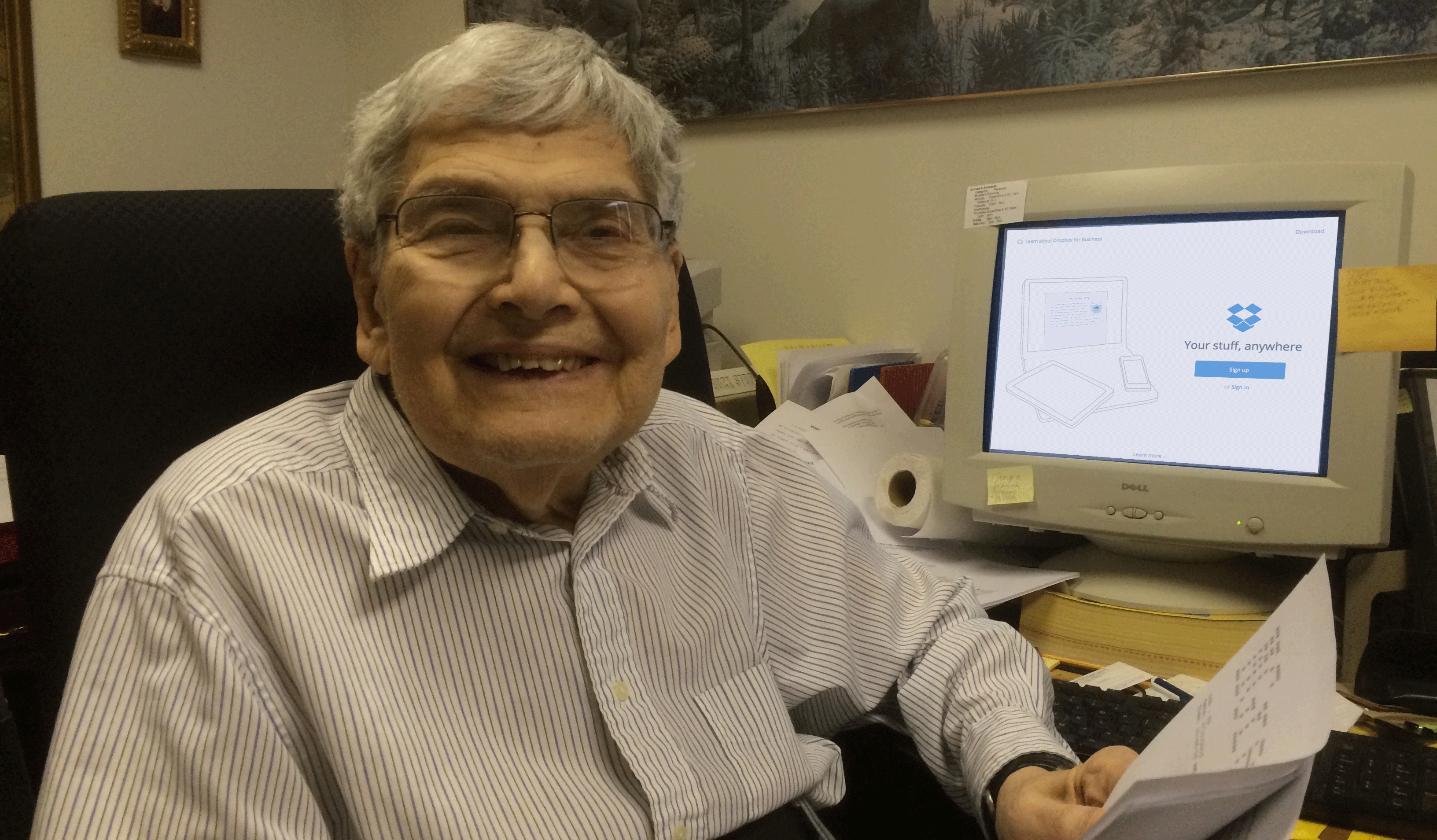

Using AI, VR, and collaborative tools such as Dropbox Replay and Dropbox Paper, they push the boundaries of architecture and design. In fact, associate partner Rana Rmeily says their goal isn’t just to design magnificent spaces. They aim to create narrative portals that feel more like walking into another world than another room.

They’re driven to continually update their techniques to engage a new generation that isn’t necessarily content to look at artifacts in a museum space. To give people a reason to look up from their phones, they know they have to create something undeniably compelling.

We spoke with Rmeily and senior exhibition designer Björn Müller to find out how they use Dropbox and emerging technology to transform spaces into immersive realms.

How has your industry changed in the last few years?

Rmeily: I would say the industry as a whole changed a lot in the sense that there's an increased integration of technology in exhibits and in experiences, from augmented reality to virtual reality, more interactive display, and emerging technologies. But also, we’re talking about virtual spaces, digital twins.

People used to travel to buildings. Now, buildings and architecture and spaces travel to you. So definitely, our field is much more accessible. I would say this is how technology revolutionized and added value to our field. Our field and the cultural sector has always been, in a way, exclusive. Making it accessible to as many people as possible is very important, because this is how growth and cultural exchange happens.

I would also say that museums are now less artifact based, less object based. They're more customized and experience based. So the individual plays a much more important role in it. You are actively asked to contribute. We're always creating expansive experiences that engage you, that put you at the center. You can influence what you're experiencing.

Of course, with technology now, this is becoming even more possible. With the AI-based tools that are being developed, having specialized content linked to your preferences—if you're experiencing a physical space, then you can customize the content for you, be it from an auditory or visual or even light perspective based on the visitor preference. The options are endless.

“With the AI-based tools that are being developed, you can customize the content... based on the visitor preference.”—Rana Rmeily

Have you started incorporating AI and machine learning into your creative process?

Rmeily: Yeah, we have. We work a lot with ChatGPT and Jasper to research topics, create mind maps, organize thoughts, create basic texts for presentations, or share our concepts. We also use it in Miro, more for the brainstorming part of the process.

Then we use imaging systems such as Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, sometimes DALL-E as well. Those we use mostly for starting the creative process, creating a mood board palette, initiating or igniting thought, sharing some elements between us, or if we want to explain our concept.

At the moment, we use it in the first phases of our work. So it hasn't been integrated fully in other phases yet. For us, it would be interesting to see how this can be a helpful tool for prototyping, developing final drawings, budgeting, planning, even using AI to analyze visitor feedback.

There's a lot of opportunity to grow and expand in this. That's why it's interesting for us, but we're still at the start. I think it’s our role now to see how this could apply more to our field and how we can push it further.

Would you consider yourselves early adopters of technology?

Rmeily: ATELIER BRÜCKNER is a big office. Everyone has their way of doing something. For example, our team is excited about technology. Other teams also value the beauty of the craft. So they still produce beautiful models rather than using the VR goggles. Whereas other teams use VR, transport the clients through the space, etc. There is still this balance, which I think brings a lot of added value. Because, of course, the moment you let go of the past, instead of informing yourself from it and keeping it in your process, then it's a bit of a hollow experience overall.

From my end, I think there is great potential. I believe now, with the AI tools that we're using, they’re not at a point where they can exist by themselves and produce by themselves. But at the moment, they are here, I feel, to facilitate our process. I can see it in our daily process how much faster boring tasks are—to research something, to find the moods and share them with colleagues so they understand what you're talking about—and in some cases, giving you some creative sparks, which makes the process much more efficient.

Müller: This directly connects to the last half year with the emergence of ChatGPT and Midjourney. We are looking really closely at how we can make this a tool for us. How can this become an extension of the ATELIER BRÜCKNER process? How can we shape this tool to not just output any kind of images but our images? Because there is still a philosophy behind it all.

“With the Museum of the Future, we worked in collaboration throughout the process... with artists, technologists, and scientists.”

What’s your process for brainstorming, iterating, and getting to consensus on concepts?

Müller: It always starts with research—getting an idea for what we are actually talking about. Sometimes there are already sparks, glimpses of “This could be an element.” So you start connecting some snippets and pieces.

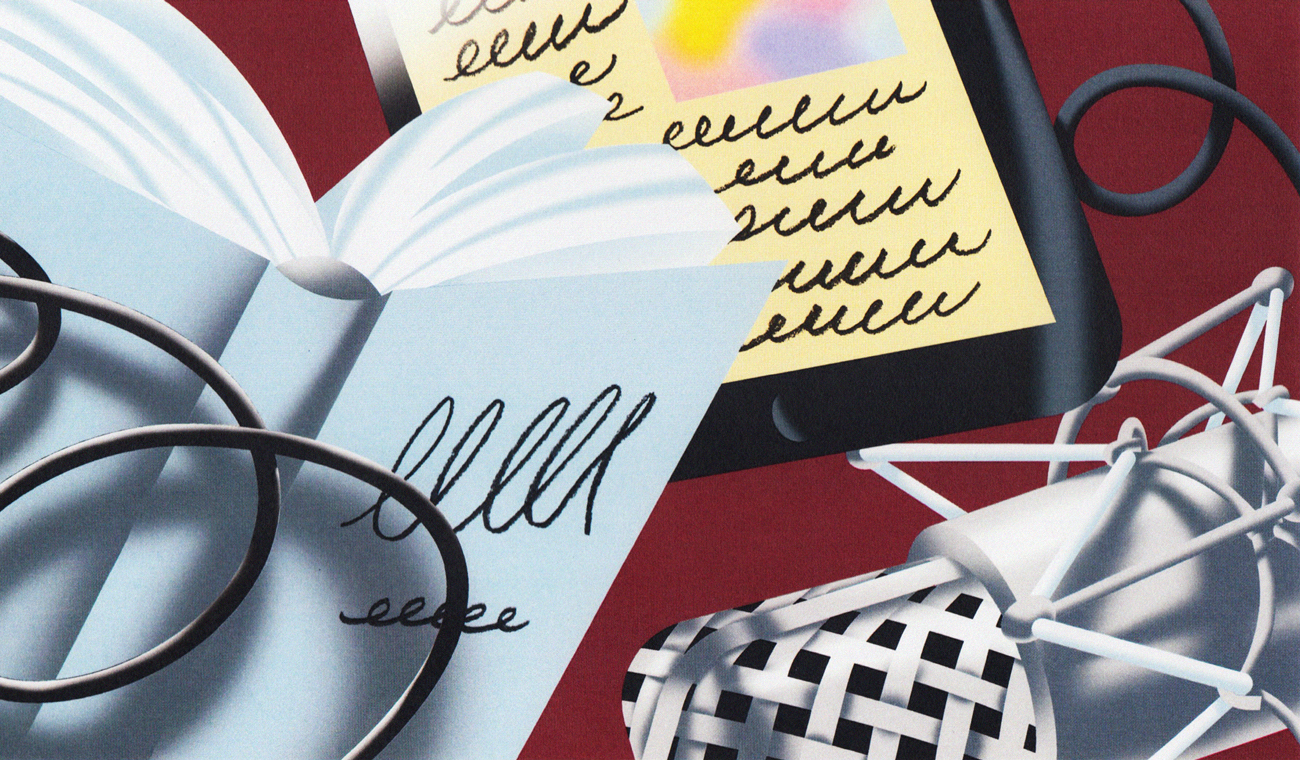

I always have the feeling that Dropbox Paper is pretty helpful for this because you don't have to think about structure. There's no right or wrong. There’s a digestion process, inviting colleagues. Then Rana is putting in, “Okay, maybe this could be related to… “ Then you start cleaning it up, compressing it down, and see what would make sense and what helps the story we would like to tell.

Do you share that initial ideation doc with the client?

Björn: Not at that stage. Because 80% of references would only make sense for me or the person who put it in.

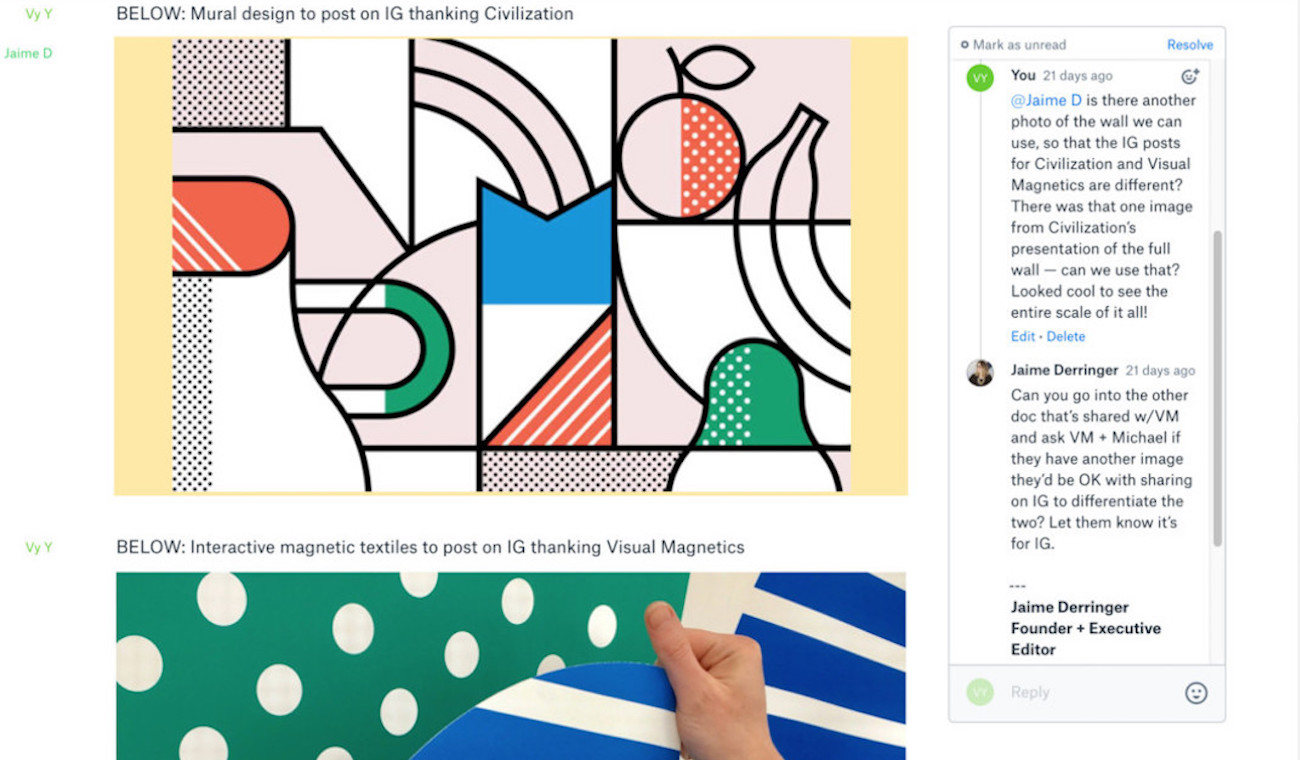

Rmeily: But it also depends on the client. ATELIER BRÜCKNER is very flexible. The teams and the structure, and how we work morphs and adapts to how different teams or clients like to work. And co-working is important. Tools that allow you to co-work—be it Dropbox or other tools that other team members in the office use—where you can share ideas and collaborate together are ones we use a lot.

Another part is the planning, organization, scheduling, and conferencing. For those, there are so many tools at the moment. They're not streamlined in our industry. It would be great if they would be streamlined, because every time we're working with a different entity they use a different planning tool—for example, Notion versus Merlin.

So it would be great—and I think this is what Dropbox now is offering—to have something that could consolidate it all. Because a big part of the process is the coordination in the interdisciplinary field and with stakeholders… especially now that everyone works remote and from different places.

“It always starts with research—getting an idea for what we are actually talking about... Dropbox Paper is helpful for this because you don't have to think about structure.”—Björn Müller

Could you give an example of how you’ve developed a concept for a recent project?

Rmeily: Our process starts by sitting with the client and creating a content workshop where they share their vision, what they're imagining, how they want to interpret the specific thematics or contents that they're tackling. From there, we take this more curatorial or historic content, then we shape it and transform it into narrative, spatial content. Throughout the process, we start involving all the different disciplines that could start imagining how this content can be shaped spatially and enhanced through media, graphic design, light design, sound design.

Of course this is a difficult topic, because how do you define something that has not been experienced or doesn’t exist yet? To do that—for example, with the Museum of the Future in Dubai that opened last year—we worked in collaboration throughout the process, not just from within ATELIER BRÜCKNER cross disciplinary people, but also with artists, technologists, and scientists. We worked with the consultants from NASA, bio engineers, genetic engineers, etc. We tried to imagine with them how the future in the year 2071 would be.

After imagining this possible future, we created these in-worlds that transport the visitors into the future in outer space, the future on earth, and the future in the inner self—your connection back to yourself, your senses and to each other. This exhibition exists in a space, which is the Museum of the Future in Dubai, but within that space, you're transported fully into other expansive spaces.

In a lot of cases, when we say we translate space or the content into spatial narrative, when the client comes, sometimes they think they also need a space, but sometimes it completely changes. So it can shift depending on who we're communicating with and what we're trying to say. We also always develop that with them.

Which part of your job gives you the most joy?

Rmeily: For me, the biggest joy is this concept of transpositioning. Whether I'm exchanging with an artist or media designer or product designer, it's so stimulating. Every time, you have to delve into different topics and meet people who are so familiar with the field that they are working, whether it be history, anthropology, brand, etc. Then you have to collaborate and sometimes switch roles. That's why I say transpositioning: to switch roles between different disciplines, learn from them, engage with them. Then each time, you create something new. This really collaborative work for me is always very stimulating, and you learn a lot from it.

Müller: This is definitely also something I enjoy throughout this process—getting completely different inputs in your own design process. But at the same time, really being able to get into the zone—digesting a specific topic, getting the idea of “Okay, I think I understand.” Then being able to shape this. At the end of the day, you have something where you look at it and think, this is absolutely the correct and perfect outcome for this specific task or topic. If you're lucky, the client thinks the same.

Rmeily: Another thing that’s interesting with emerging technologies is that each time you’re thinking: What kind of sensory tool am I going to use to translate the content? Because now, there's a big menu of options. It's tricky for us each time to decide, because you can easily fall into the trick where the media is guiding your approach. We usually try to use media just to facilitate rather than letting it guide the full spatial process, that narration in a space. So each time, figuring out the tool that’s gonna evoke specific emotion and create emotional engagement for the visitor and also give them empathy to an object or each other or to their surroundings.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed.