How BBoy City shares 25 years of breakdancing history—and keeps it secure

Published on June 26, 2025

Any hip-hop head worth their Air Force 1s knows breakdancing began in The Bronx, New York City.

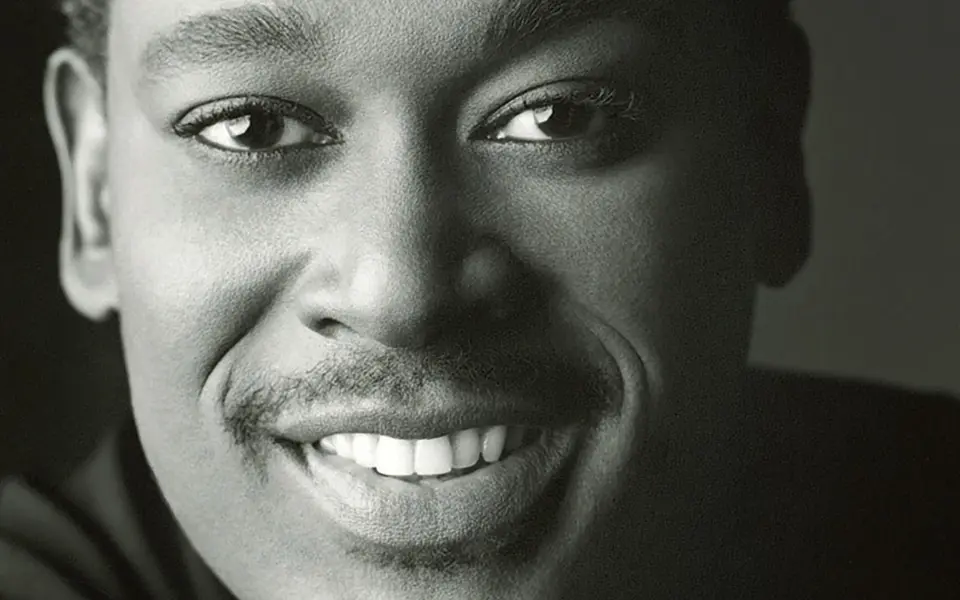

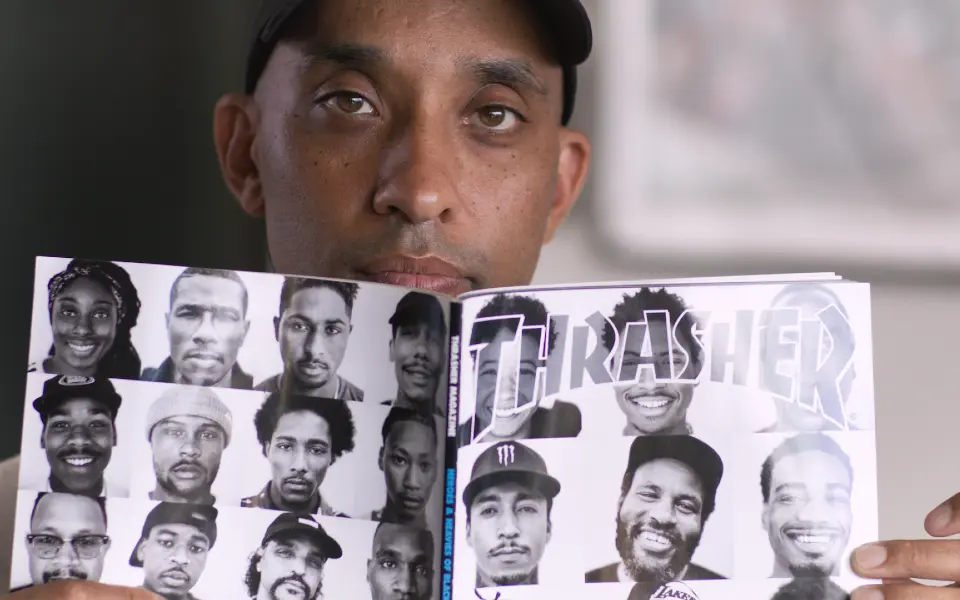

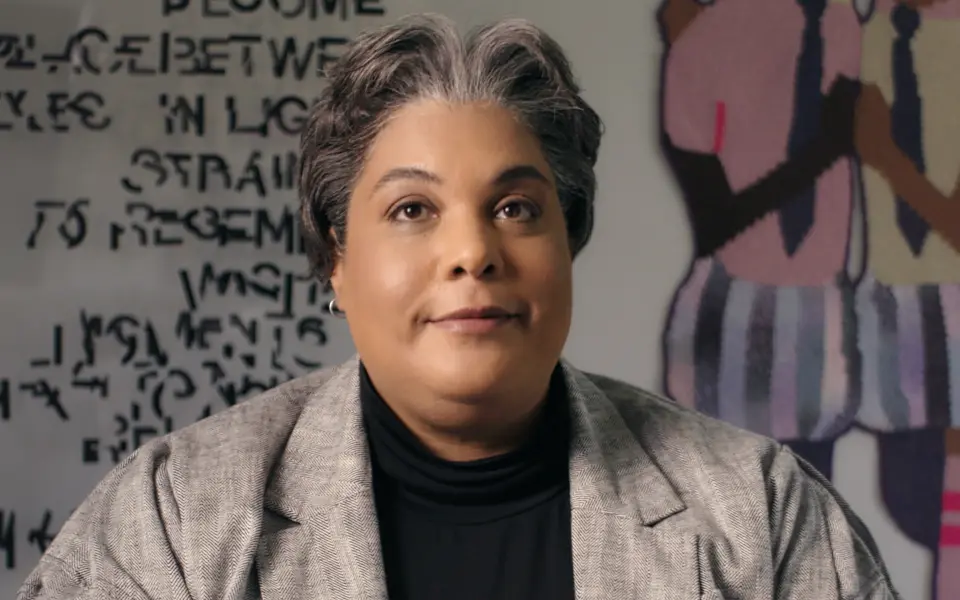

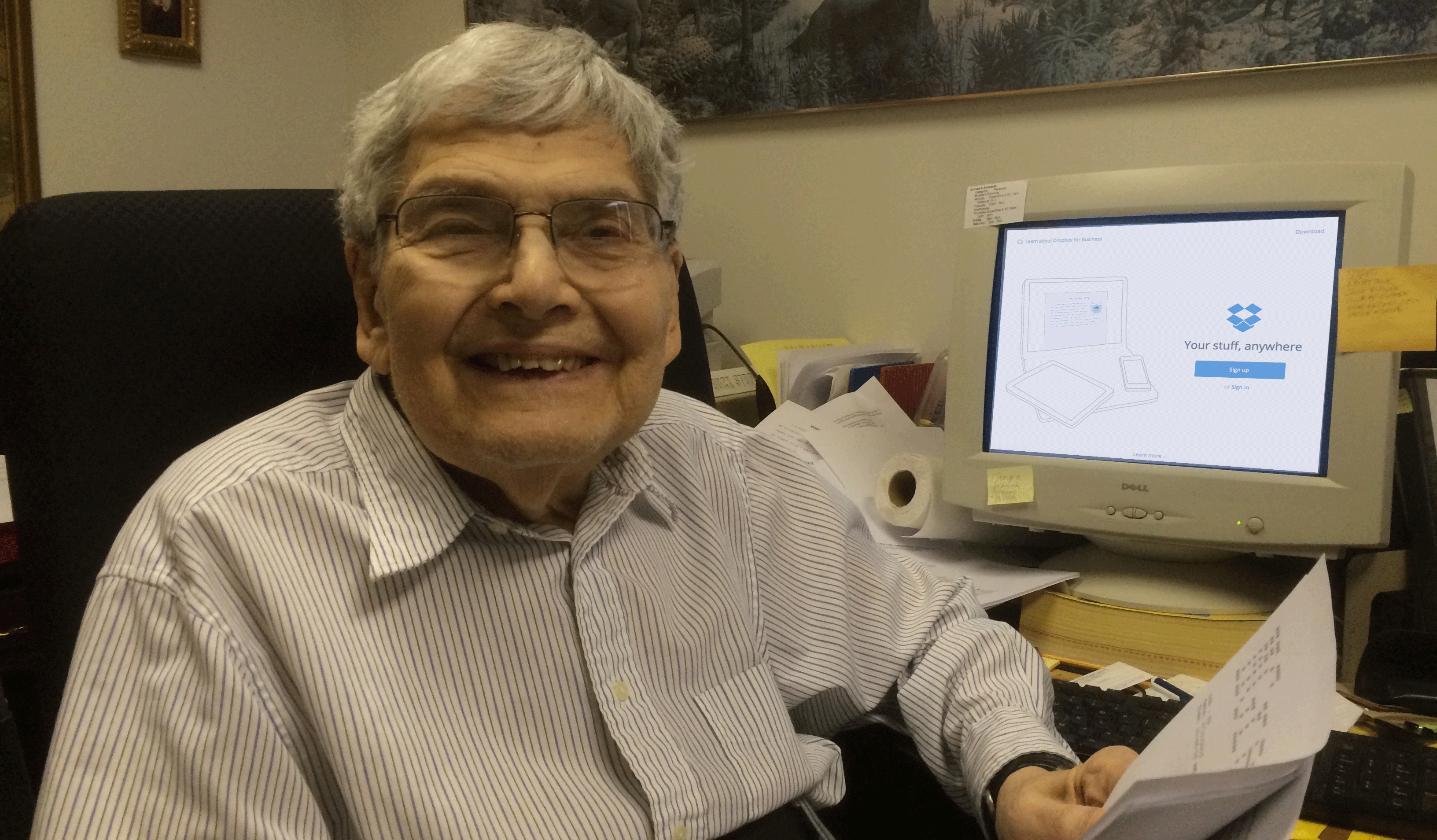

But breaking (the community’s preferred term) has found its footing on streets and stages beyond New York's five boroughs, thanks to videos of b-boys and b-girls battles. Sharing the culture is key to its growth and survival, says firefighter and b-boy Romeo Navarro. And for more than 25 years, his Austin-based BBoy City has helped take the art from New York to Texas to Paris, France for the 2024 Games.

Founded in 1998, BBoy City produces events, media, and films to showcase up-and-coming dancers and the culture around the art. A team of photographers, videographers, and editors (some of whom are breakers themselves) create and share content across social media, YouTube, and streaming, and through licensing agreements.

In many ways, broadcasting this content pays homage to breaking’s roots, according to Navarro.

“Our culture is about showing proof. You can talk about it, but did you do it?” he explains. “If you got footage and content, you can show and prove.”

By 2019, BBoy City had tons of evidence. Every event produced hours of footage. Navarro started thinking about breaking’s legacy when his kid became a breaker. He had decades of personal and BBoy City footage stored on external hard drives and VHS tapes. Those videos were all part of breaking culture and history. That need to document, share, and elevate led Navarro and his team to rethink how they managed BBoy City’s growing archive.

“Dropbox has helped us organize all of our footage and share a bunch of it real fast,” he says. “I don’t have to put it on a cassette tape or download it, wait, and then send it.”

Being able to share their content quickly has helped BBoy City grow while staying rooted in Austin. Navarro and his team host an annual competition that’s the largest breaking event in the South. BBoy City has branches in Africa, Asia, and Central and South America. In 2023, the International Olympic Committee announced breakdancing would be a sport in the Paris Games. Navarro co-hosted the National Finals, a key qualifier for America’s team, produced by Breaking for Gold USA. All four American breakers made it to the Games through that event.

But just because breakdancing made it to the podium doesn’t mean BBoy City’s work is done. Like hip-hop, Navarro and his team can’t stop and won’t stop. Using Dropbox products like Dropbox Sign and Dropbox Replay, help them do just that.

Putting Austin on the B-boy map

When Navarro first discovered breaking, he had no idea how far it’d take him. He was just a smitten 12-year-old boy.

“I was a kid, already in the streets, no father figure,” he explains, “but I was in love with the meaning of the original b-boys. The origin of hip-hop was peace, love, and unity—and having a good time.”

Few may realize it, but when breaking started, it was more than a dance—it saved lives. After a prominent neighborhood peacekeeper was murdered, a coalition of rival gangs proposed a truce and, with it, a promise: To honor his memory, they would handle beefs differently. Throwing down would mean proving you were the best on the dance floor, not in the streets.

“I wanted that,” Navarro says now. “I didn’t want to go to jail. I didn’t want to die. A couple of my friends died. A lot of them went to jail.”

Navarro found care, community, and catharsis in breaking. That instinct to protect and uplift has guided him ever since—whether he’s on the floor or in the firehouse. Eventually, he became the OG looking out for younger breakdancers when he started BBoy City. Many left gangs to practice and compete against each other in local recreation centers and garages. The more time the youths spent “breaking on the floor [instead of] breaking faces,” as Navarro puts it, the better they got.

"Instead of having to write an email that describes what I want, I can just show the editor a specific frame in Dropbox."

But breaking competitively wasn’t easy. Austin wasn’t plugged in to the event circuits that garnered media attention and sponsorship. So Navarro decided to follow the advice he often gave the kids: “‘If they ain’t going to put you on, put yourself on.” BBoy City would host their own events. Being underestimated all his life only fueled Navarro’s drive.

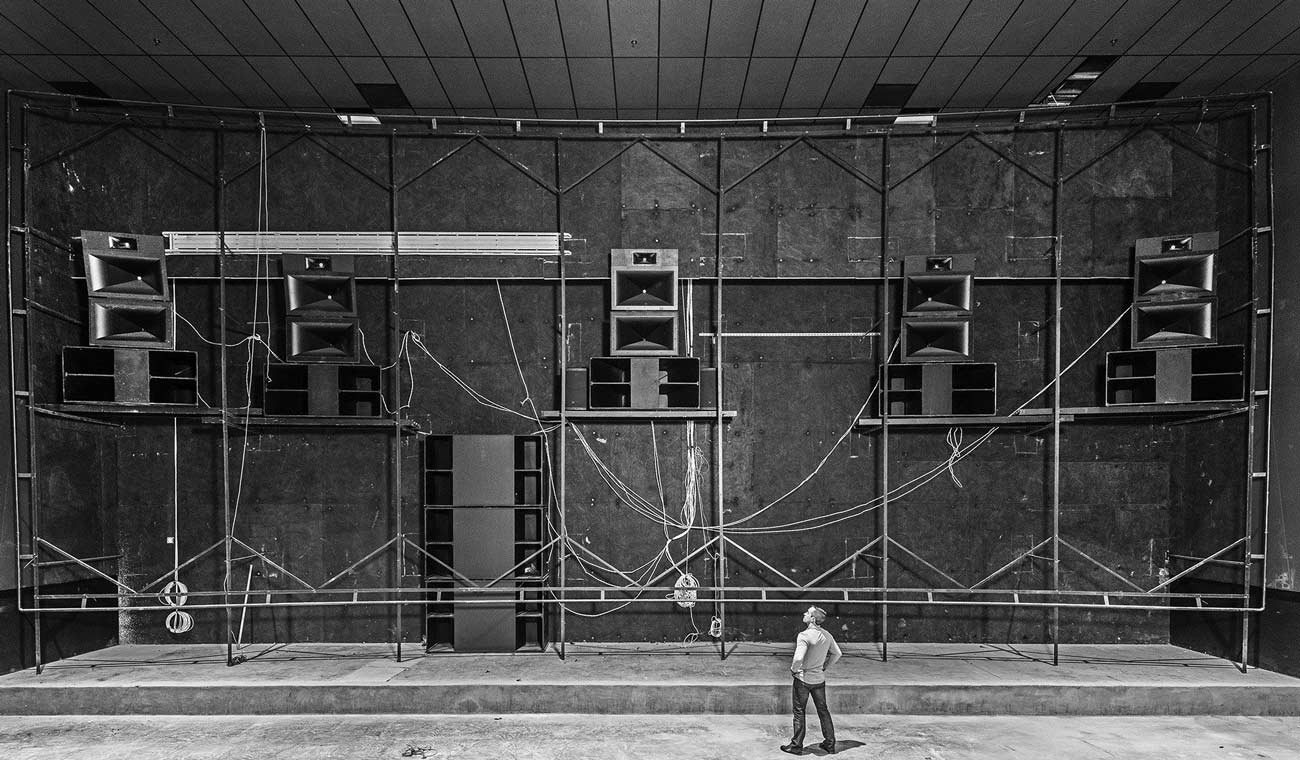

“‘You know what?’” he recalls thinking. “’I don’t know anything about sound systems or any of that stuff, but we’re going to learn.’”

Getting BBoy City on screens

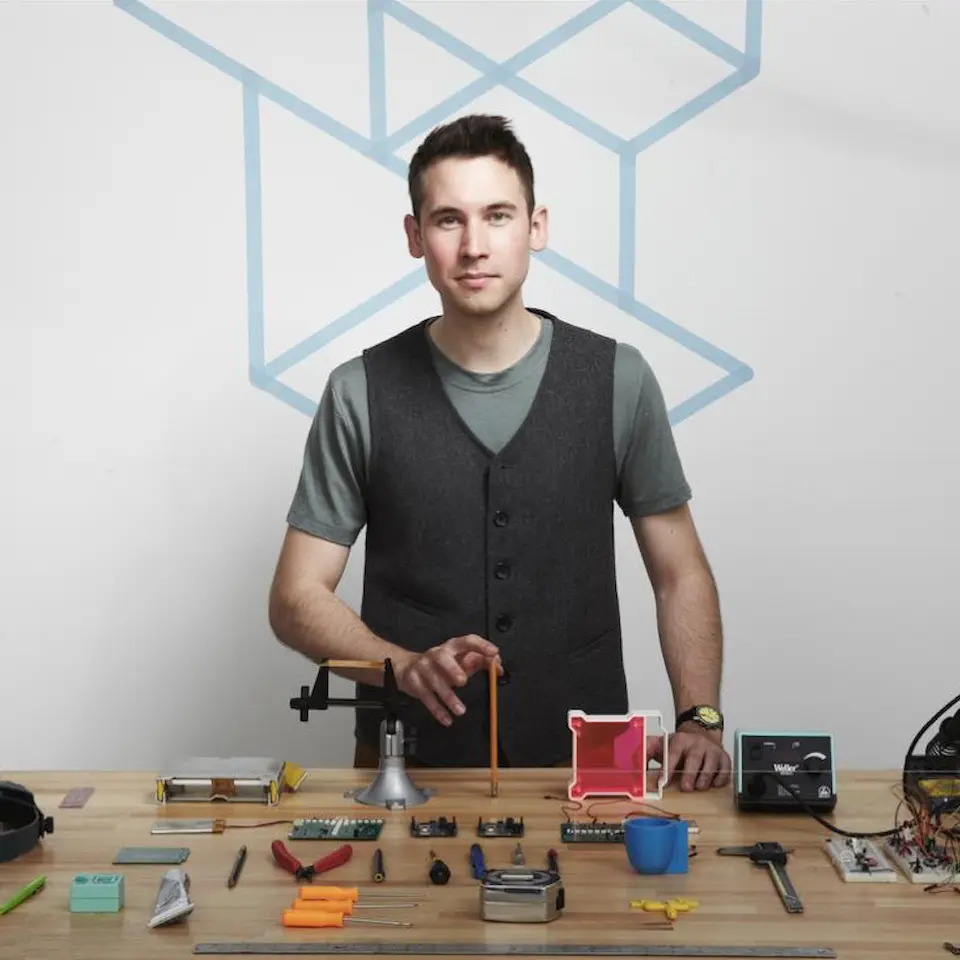

Video production was on that “to-learn” list, too. Thankfully, Navarro knew a guy: longtime friend and documentarian Michael Plaster. (The two originally met as dancers more than 20 years ago.) Plaster is now BBoy City’s production partner.

“A big part of my job is to just document and get out of the way,” Plaster says.

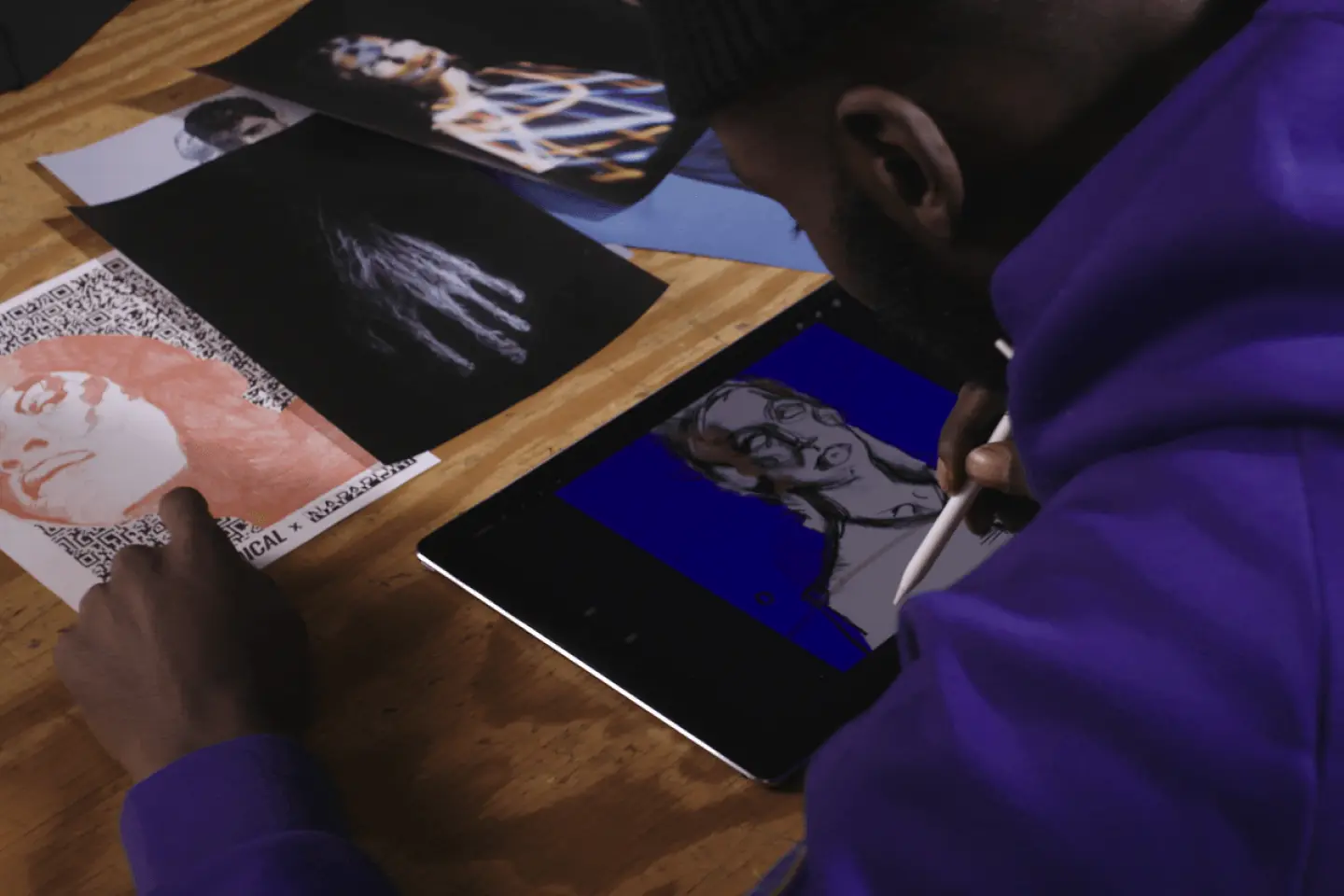

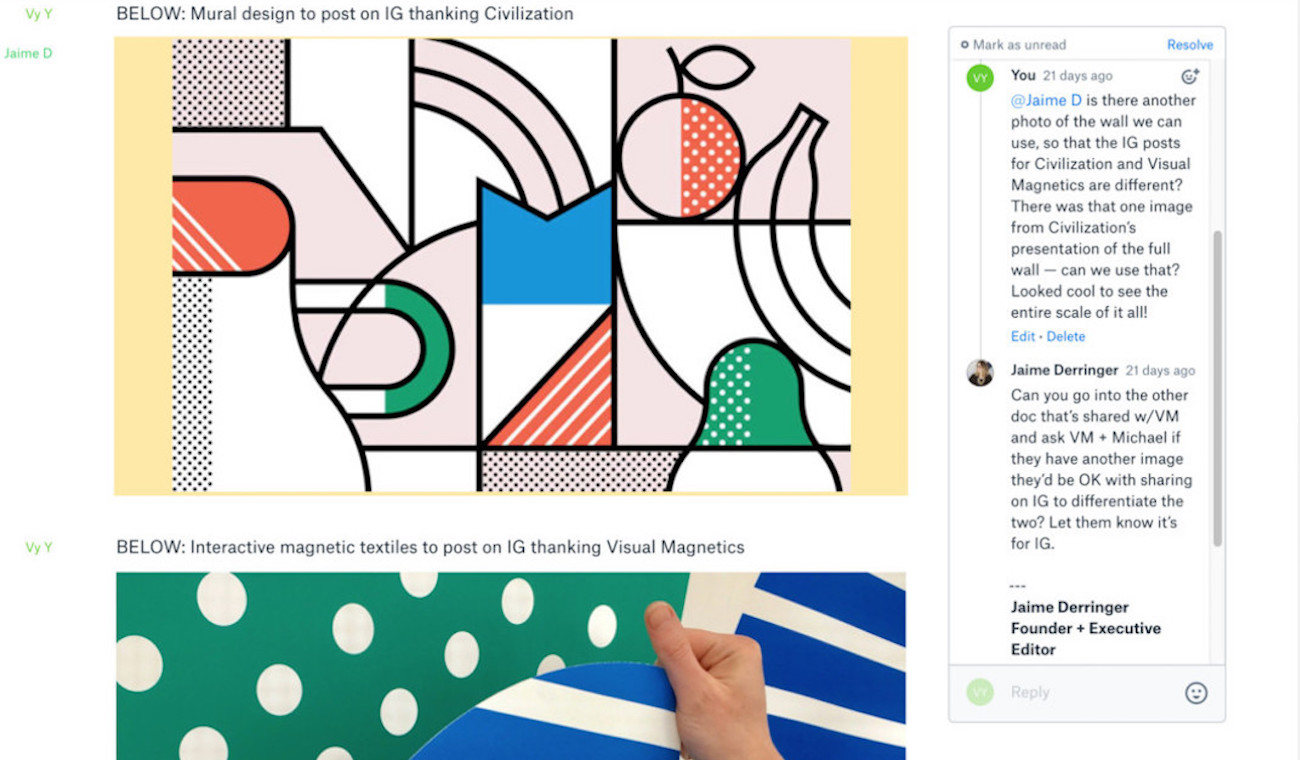

And there’s plenty to document: BBoy City’s annual competitions, emerging dancer stories, multi-city tour performances… To stay organized, the video team developed an easy-to-replicate workflow with Dropbox serving as the single source of truth. Plaster shares an outline of the event, including important characters and shots, with his team ahead of time via Dropbox.

“The whole production day is [then] spent focusing on getting the stories. But as soon as the event’s done,” Plaster says, “we’re uploading terabytes of information in Dropbox for remote editors to go and grab and start laying down the videos.”

With that much content to go through, anything that speeds up the process is appreciated. Instead of watching hours of footage, Plaster uses the transcript feature in Dropbox to find the moments he’s looking for.

“Another thing I use the transcriptions for is to create an outline with citations on what’s being said and when [through] an AI service,” he says.

And Dropbox Replay allows Plaster to annotate video and give editors further direction with down-to-the-time-code notes.

“The most important thing for me as a creative is to collaborate—that means sharing my thoughts and ideas as well as getting other people’s thoughts and ideas,” he explains. “And the best way to do that is by visually representing that on the screen. Instead of having to write an email that describes what I want, I can just show the editor a specific frame in Dropbox.

“I’ve been looking desperately for years to put all these aspects together,” Plaster continues. “Now, with the features Dropbox is providing, as well as the rise of AI, it’s all coming together.”

“We’re celebrating life…”

BBoy City works hard to celebrate the culture that’s given many of them so much. In 2023, hip-hop celebrated its 50th anniversary. The following year, BBoy City celebrated its 30th competition with a block party, film festival, and two-day dance battle.

“All the old heads showed up,” Plaster recalls. “We had lots of new blood, [too], and everyone was super sentimental about bringing it back to its roots in a club.”

The timing was kismet. It was shortly after breakdancing’s debut—and a hometown hero’s medal-winning performance—at the 2024 Games. Victor Montalvo, who won gold at the 2023 qualifiers, brought home a Bronze medal for America.

“I still couldn’t believe it,” Navarro says now. “I was like, ‘I don’t know how we got here, but we’re here.’ It was the biggest commercial for our art… Now people think breaking is back.”

But for Navarro and BBoy City, it never left.

“We’re celebrating life every time we get together,” he says. “Some people only dance during weddings. We dance all the time.”

Melissa Kimble contributed reporting.

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(2).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/1200x628%20(5).webp)