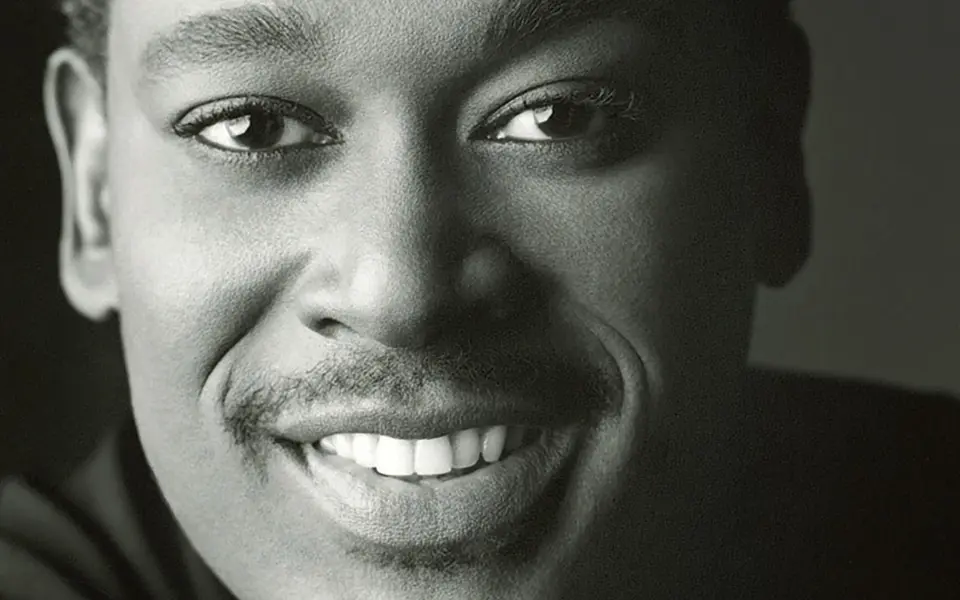

This founder is following her curiosity—and helping others do the same

Published on May 19, 2023

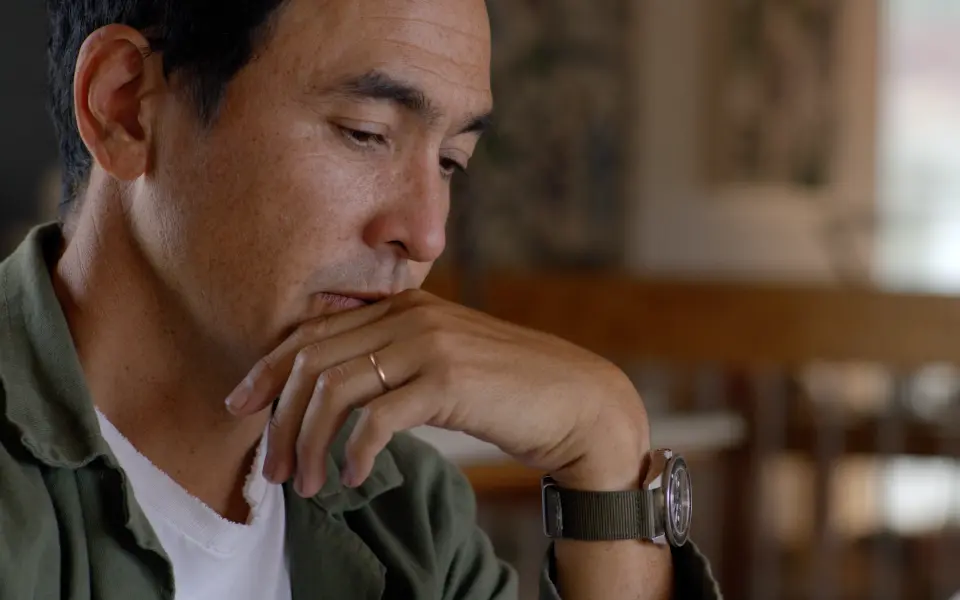

By never being afraid to ask questions, JinJa Birkenbeuel is helping creatives and business owners find their truth.

Two things to know about JinJa Birkenbeuel. One, she does a lot of things and two, she asks a lot of questions.

It’s something she used to get scolded about as a child, but she’s embraced it as just part of who she is. She’s even made a career out of it as the founder of creative marketing agency Birk Creative, a Google Digital Coach for entrepreneurs, and the host of The Honest Field Guide podcast.

Sometimes her questions are rhetorical. Sometimes they’re asked to help her clients course correct and shift their mindsets around technology and marketing. But no matter the type of question she’s asking, she’s ultimately asking for the same reason—to help people (especially those who don’t have easy access to experts) get the answers they need to thrive.

“If I’m not finding ways to tap my own expertise to bring someone else up, then I’m being greedy,” Birkenbeuel explains. “And that’s just not the kind of way I want to live.”

Although her mother—who taught English in the Chicago Public School district—dissuaded her from entering her profession, Birkenbeuel is a natural teacher. At Birk Creative, she helps companies wondering “How do we reach Black and brown audiences?” launch relevant and dynamic campaigns that do just that. And as one of the architects of Google’s Digital Coaches offering, she helps underrepresented small business owners answer the question, “What digital tools do you need to legitimize your business?” That knowledge came from Birkenbeuel’s experience with using tools like Dropbox Capture to get screengrabs for her presentations and Dropbox Sign to sign and store contracts while she’s on the go. (“The very first time I had a digital contract,” she says, “I thought, I am never going to have a paper contract again for as long as I live.”)

In 2018, she was inspired to launch her podcast The Honest Field Guide, thanks to the encouragement of a student she was teaching the ins and outs of creative strategy to at the time.

Her guests and the topics discussed are as varied as Birkenbeuel’s interests. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen talked to her about how he alchemized his family’s collective trauma as refugees to become an entrepreneurially minded creative. Then there was her chat with Sprinkles Cupcakes founder Candace Nelson who shared the cognitive dissonance she experienced going leaving the “man’s world” of investment banking to reconnect with her love of baking.

“I just interviewed Doreen Lorenzo and she’s the assistant dean of the University of Texas, Austin’s School of Design and Creative Technologies,” she says. “That’s a really interesting interview.”

The very first time I had a digital contract,” she says, “I thought, I am never going to have a paper contract again for as long as I live."

Much more than a token creative

Having confidence in her voice and where her curiosity takes her is what led Birkenbeuel to strike out on her own in the first place.

After college, she worked for a global consulting agency with offices in her hometown. Birkenbeuel had grown up in Hyde Park, a then largely white, academic, and hippie neighborhood in the South Side of Chicago. She was the first Black student to graduate from the school of fine arts at her college. But nothing prepared her for the distinct flavor of being “the only one” that she experienced in the corporate world.

In school, Birkenbeuel would stride into rooms and hear, “You’re gonna be a CEO one day.” But at work, people would either ignore her or crane their necks to look past her, searching for “the boss” on projects she was heading. Save for the janitor and a mailroom clerk, she was often the only Black person in the office.

“That was the first time I really was faced with what we now know as microaggression,” she says. “I couldn’t move! I couldn’t breathe! I couldn’t create.”

She left to work for a smaller company, but still found herself placed in the same role: “the trophy Black creative,” she says, someone who checked a box, but wasn’t afforded any agency.

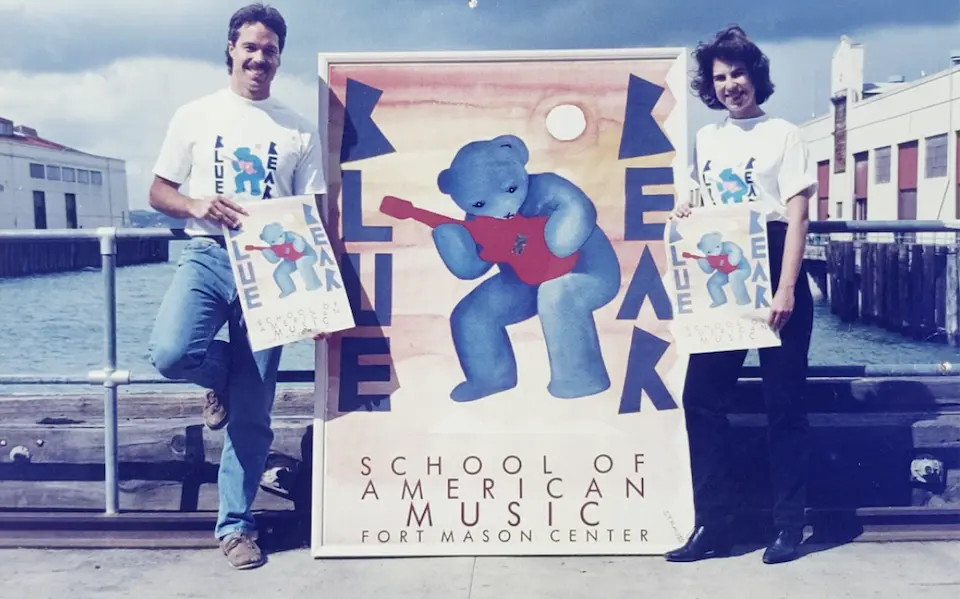

Birkenbeuel felt the most in touch with her gifts when she performed as one half of Utah Carol, an Americana dream-pop soft-country band she started with her husband Grant Birkenbeuel. When she was writing songs and recording music, she didn’t have to find a way to circumnavigate the minefield of managers’ egos and co-workers’ agendas; she could just do what she knew how to do well—and ask questions to shore up the things she didn’t know yet.

Take, for example, when Utah Carol got their first record deal offer. Birkenbeuel asked a lawyer to take a look at the contract. “How can I protect our work?” she wondered.

The lawyer guided them through the ins and outs of publishing and digital rights, most notably how eliminating the record label’s access to them would allow Utah Carol to keep making money from their work in perpetuity.

Treating her band like a business helped Birkenbeuel see that in order to work the way she wanted to, she needed to start her own company. With that—and, she says, the security that comes with having a partner with insurance and no additional mouths to feed yet—Birkenbeuel started Birk Creative. Her first client was the first firm she had worked for as an underappreciated account executive and senior designer.

Protecting what’s hers—and helping others protect what’s theirs

Since that transformative contract discussion, Birkenbeuel makes sure she owns all of her intellectual property free and clear. Utah Carol owns their masters and digital rights; all their music is stored on Dropbox and has been licensed for major motion pictures and a 30 for 30 ESPN documentary. That contract is still reaping benefits for the Birkenbeuels now—“We just got a $300 check from a song that we wrote 25 years ago!” she says. (And if some future pop star samples one of their tunes, they’ll get paid for that too.)

“If I want to give something away or not, it’s my choice,” she says. “No ones going to take my choice away from me.”

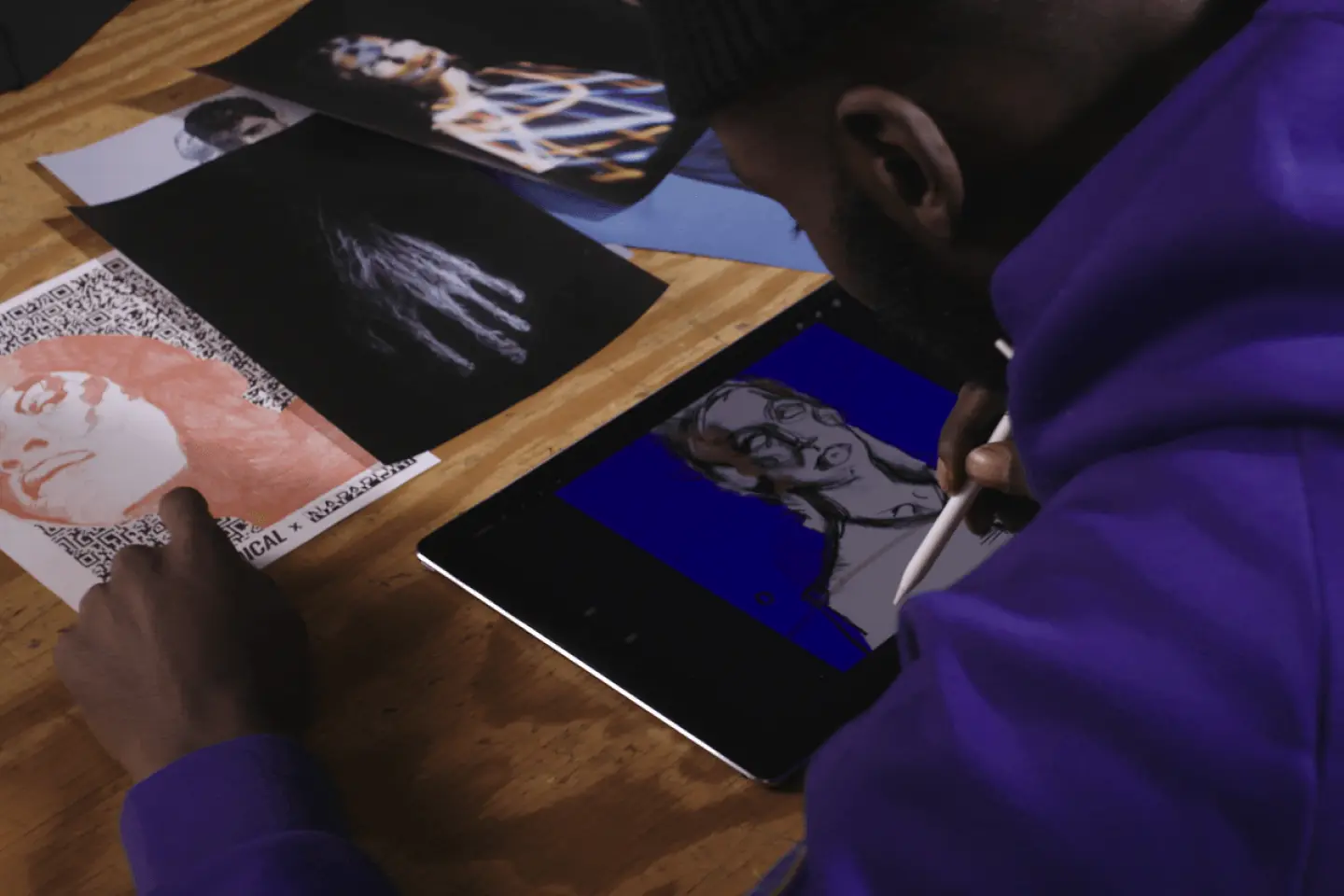

It’s a belief so strong, it’s become a part of how she parents her three artistically inclined sons.

“I’m like, ‘Look,’” she says, her voice taking on the tone that any Black person who has disappointed their mom knows immediately. “’If you end up putting some beats down on something and you don’t protect your work, you will never hear the end of it from me.’”

While she’s made sure her sons were in the know, Birkenbeuel recognized that other business owners weren’t as knowledgable (or inclined to ask questions) as she was. And that’s by design, she states.

“In the United States,” she says, “We’re raised to be consumers. We’re not raised to be creators. The conversation is never about ‘How do I become an independent financial person?’”

The businesses and nonprofit she’s founded all serve to make that question easier for folks to answer: Birk Digital, is an e-book publisher that “trains independent authors on how to build online platforms around their intellectual property” so they can maintain ownership of their work; Stomping Ground, a music production, licensing, and songwriting studio that produces Utah Carol’s work; and Journey to Gratitude, which provides personalized digital curriculums for business owners and “curious people with ideas.”

“I’ve always believed the sign that you are a great entrepreneur is when you wake up in the morning everyday and ask: ‘What can I create today?’ and not ‘What can I buy today?’” she says.

“I’ve always believed the sign that you are a great entrepreneur is when you wake up in the morning everyday and ask: ‘What can I create today?’"

Sharing the wealth

So yes, JinJa Birkenbeuel does a lot of different things. But they all feed into each other, creating a circular Birk Creative economy of sorts. Take her podcast for instance. Some of her guests are clients that she’s worked with or come across through Birk Creative. The music you hear in between segments is Utah Carol, which is produced, of course, by her studio Stomping Ground.

In doing so, she’s practicing what she preaches as a Google Digital Coach—that “’there’s nothing stopping you from doing exactly what large brands are doing on a smaller scale,’” she says. “Maybe we don’t have that kind of budget, but the tools are available for all of us to use.”

For Birkenbeuel and her team, that means producing the entire show from start to finish on Dropbox.

“Music and film require a lot of space, speed, and efficiency—and they require the ability for multiple people to access multiple things at the same time. It’s not like Excel files,” she says.

Each episode has corresponding folders for the large raw and edited audio files. Birkenbeuel listens to episodes within Dropbox and shares her notes for edits with her editor.

“I can listen to audio drafts right in the app and playback is super fast. I haven’t found this feature to be available on other cloud storage platform,” she says.

She’s recently started doing video podcasts for the show, which she posts on her YouTube channel. Those videos feature animations from artists around the world, including Brazilian illustrator Drawingzila.

With other tools she tried, finding files was like looking for “a needle in a haystack,” she says.

“You’ll be making a bunch of stuff and you will not remember what they’re called,” Birkenbeuel adds. “Even if they tell you that there’s a keyword that you can put in and it will find it, good luck. But with Dropbox, sometimes it feels like the interface is designed for things to be organized for me intuitively.”

And that kind of effortlessness is critical when you’re managing so many different projects. Not having to think about which files are where allows Birkenbeuel to be who she’s always been: a multihyphenate who follows where her interests lead her—no matter what anyone else thinks or says.

“If I let people make me feel bad for being enthusiastic, if I let that sink and integrate into my DNA, I would never ever have made it as far and done the work I’ve done and helped as many as I’ve helped.”

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/SH-06003_R%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(2).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/1200x628%20(5).webp)