How Penn architecture students are using robots to remotely design and build a pavilion

Published on May 18, 2020

The cultural portrayal of robots tends to elicit a range of emotional reactions. We’re in awe of them, at least up until the point of their betrayal. We think it’s hilarious as they struggle to learn basic motor skills, but if they progress too quickly become worried about our own security. When it all feels like too much, we turn to satire.

So when I asked Mathieu Victor, Founder of Via Domani, about his practical, near-future view on robotics and its applications, he was very clear: to do helpful things that humans either can’t or probably shouldn’t be doing.

“Construct a skyscraper 1,000 feet in the air, so someone doesn’t have to risk their life,” Victor says. “Build things on the ocean floor. Set up camp on the moon or Mars before trying to send a person. These are some of the valuable uses of robotics, and ultimately one of the main objectives of this project is to explore and contribute to these insights.”

Victor’s company, Via Domani, is a creative consultancy that brings together experts to collaborate on innovative projects. Its latest initiative connects the University of Pennsylvania and LeMond Composites, a manufacturing company focused on scaling the usage of carbon fiber.

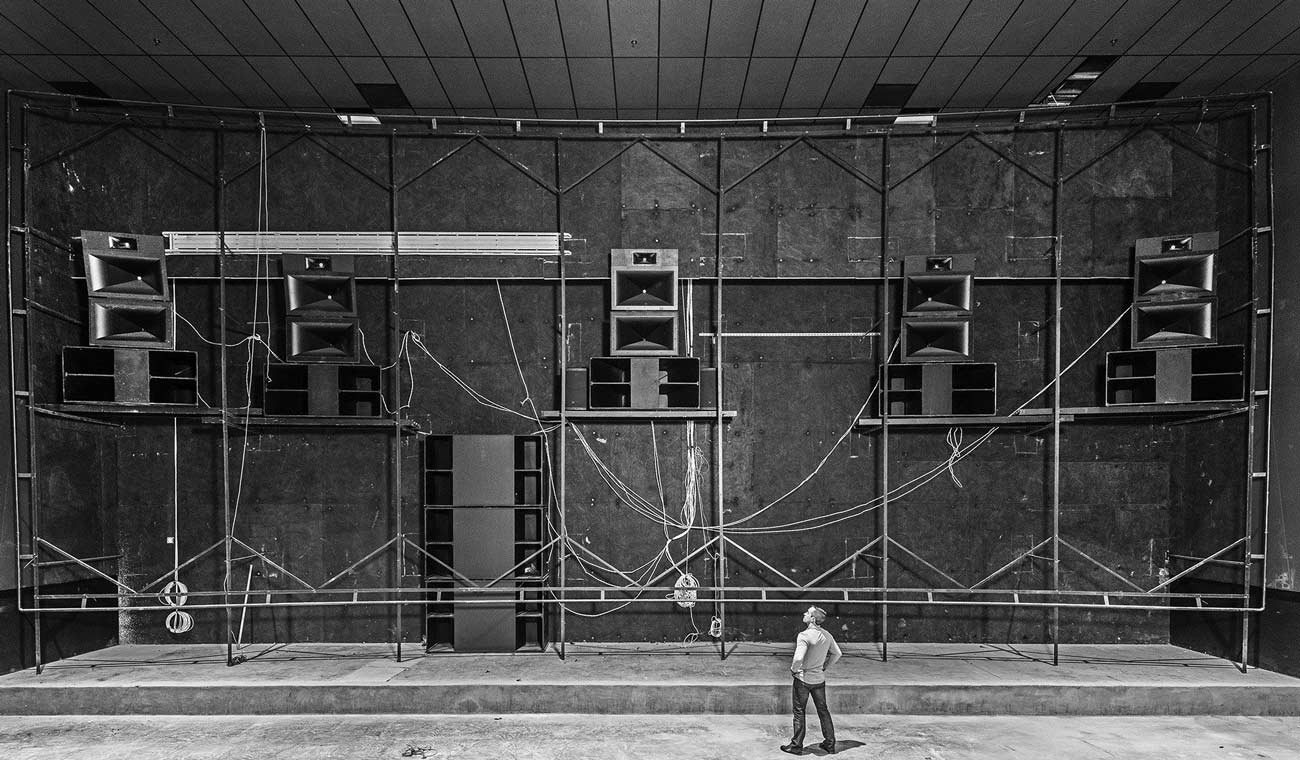

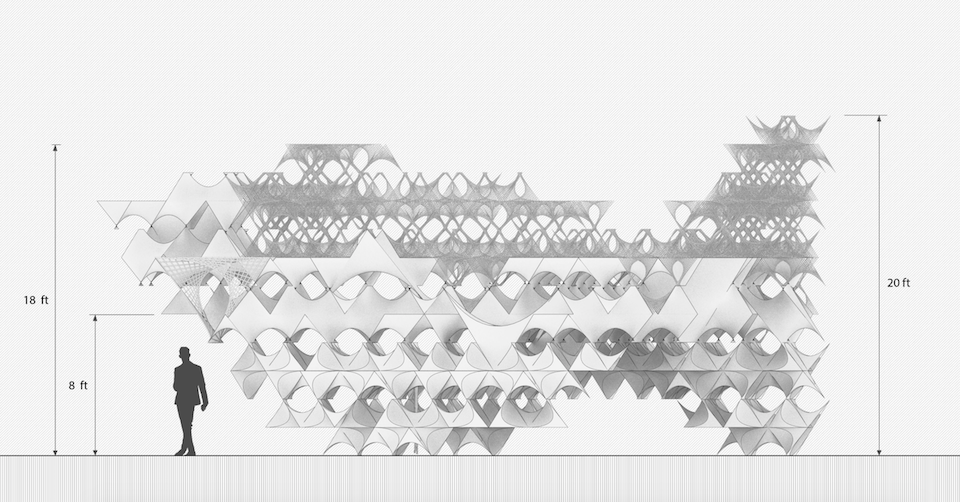

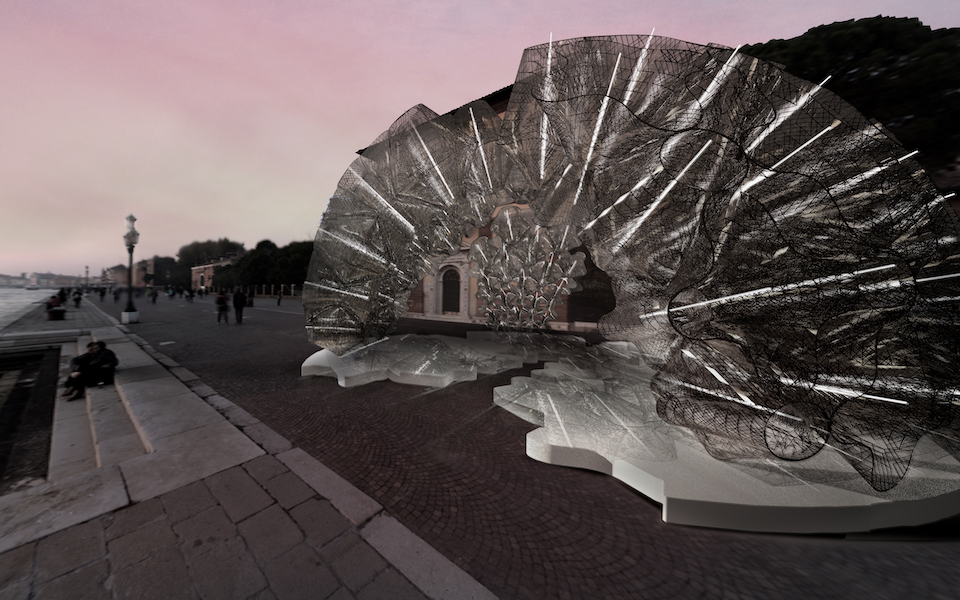

Together, this unexpected team is using robotics to build an exhibition for the Venice Biennale, one of the highest-profile architecture events in the world. It’s aiming to showcase not only the power of robotics, but how to harness carbon fiber—a strong and light material typically reserved for exotic aerospace purposes—for more common use in construction.

“The challenge has always been about supply, price, and, as a result, number of people who know how to use it,” says Greg LeMond, founder of LeMond Composites, who first developed the carbon fiber bicycle frame for use in his multiple Tour de France-winning career. “Our goal is to open up the market beyond specialty purposes to architecture more broadly—for example, to make a bridge more earthquake-resistant. Instead of keeping things secret, we want to democratize its usage, and this exhibition is part of that effort.”

Got all that? Robots using game-changing materials.

As if that’s not ambitious and complex enough, then COVID-19 happened.

From in-person to virtual

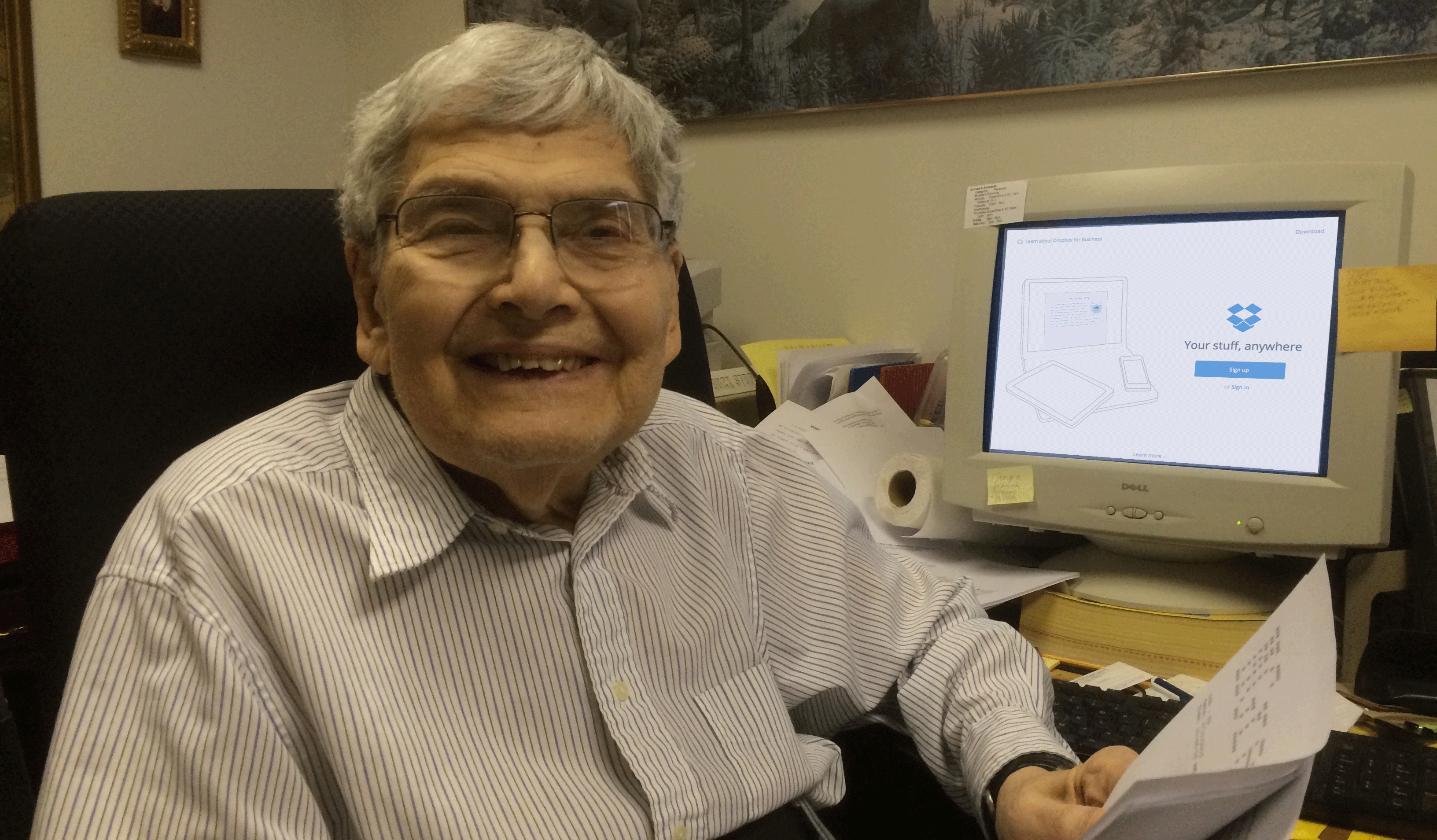

“Architects are very hands-on,” says Ezio Blasetti, professor in the Graduate architecture program at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design. “Many aspects of this class were designed to be in person.”

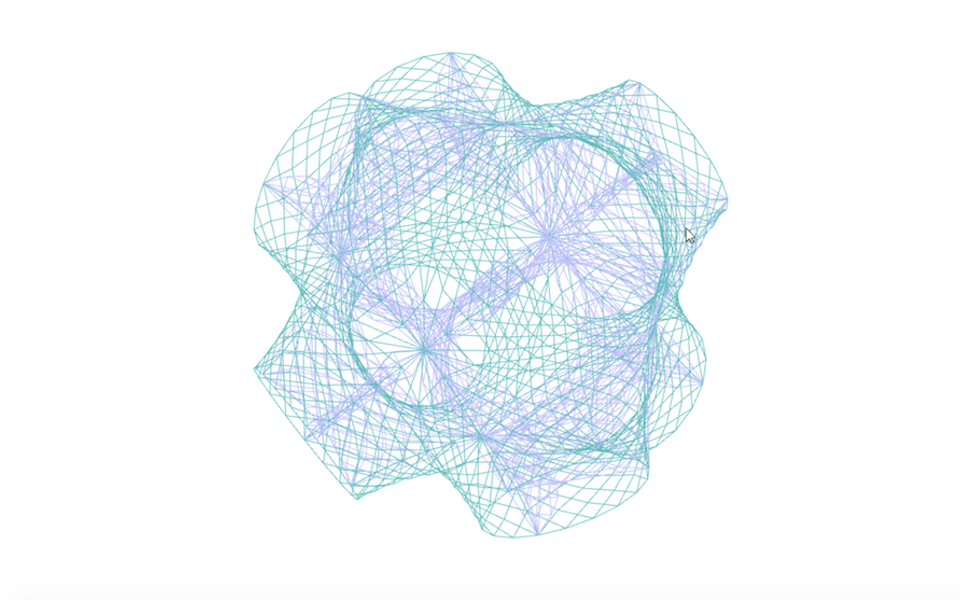

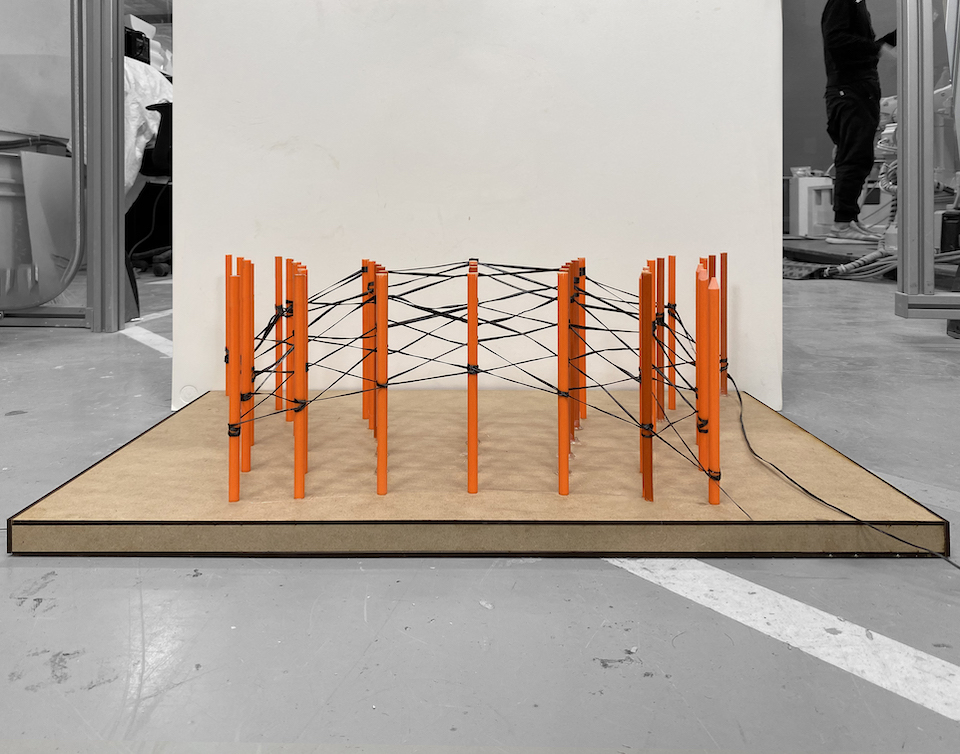

Blasetti and his students in the seminar, Computational Composite Form, are the brains behind the robots. They team up in groups to program various parts of the robots, and, before the pandemic, would trial their fabrications in Penn’s robotics lab.

“One of the biggest challenges is transitioning from software analysis to actual applications with the hardware—in this case, carbon fiber,” says Penn student Kevin He. “It requires a great deal of coding and testing, while being able to observe how the material reacts. We’re learning how to create patterns of carbon fiber by coding the robot arm to weave in specific ways onto a mold. All of this requires a lot of discussion and teamwork.”

Still image: Weaving Diagram, Discrete Flux, by students Gordon Cheng and Jean Yuan. Video: Compilation of animations from the seminar featuring work for the Venice Biennale

But on March 11, like so many schools around the world, Penn closed its campus to slow the spread of COVID-19. This included the robotics lab. “Our whole schedule got turned upside down,” Blasetti says. “We were supposed to be delivering pieces to Venice in March for the May event, and installing them in the exhibition. Instead, we were just in the chaos of transitioning off campus.”

Thankfully, Blasetti and his students did settle into working from their homes. While the status of 2020’s Venice Biennale is now up in the air, the class is pressing forward from remote locations. It’s all been an adjustment.

“Dropbox Spaces has been really helpful in keeping everything in the same place and organized. We're using it as an operating system for our collaboration."—Ezio Blasetti

“Your routine is totally different,” says Penn student Rebeca Sanchez. “You're trying to work in a space that doesn’t feel like school, and you're removed from the support system of being on campus. But it is really great that we already have the technology in place and can actually continue a lot of our work.”

Setting up a new space

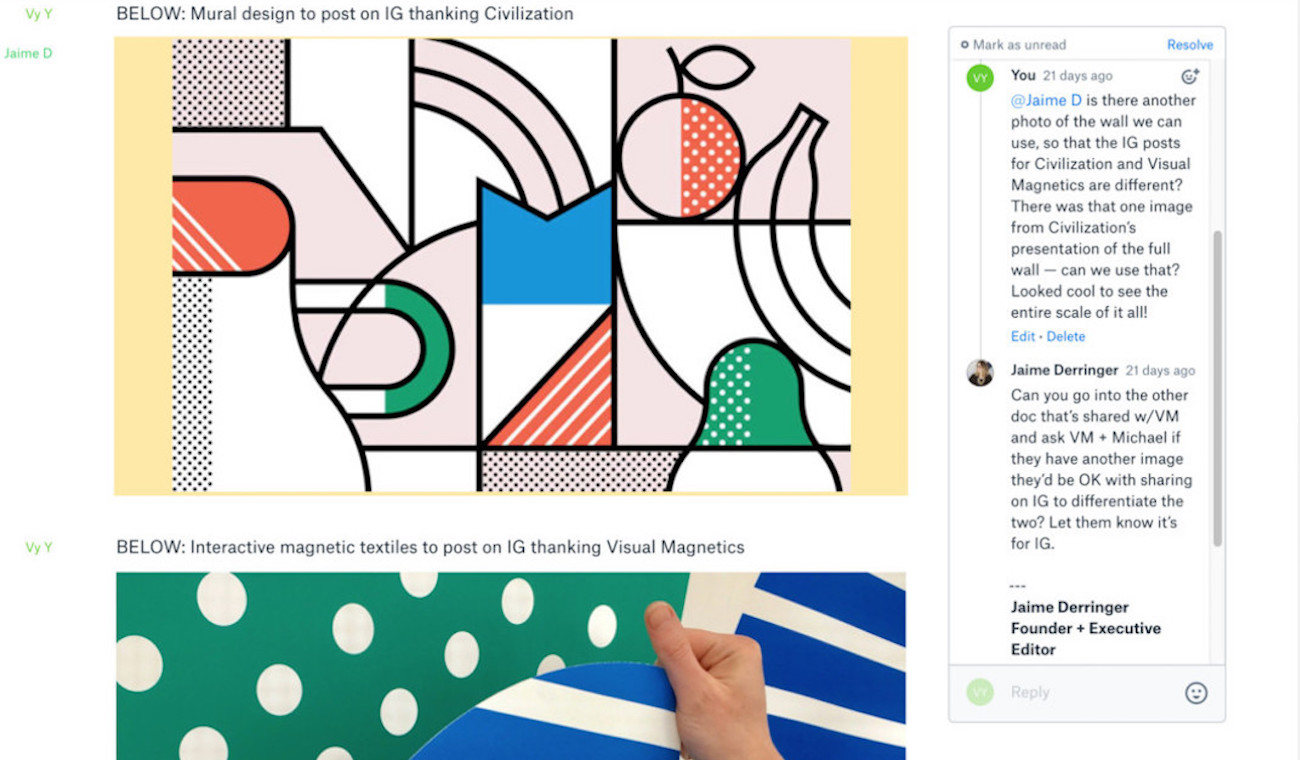

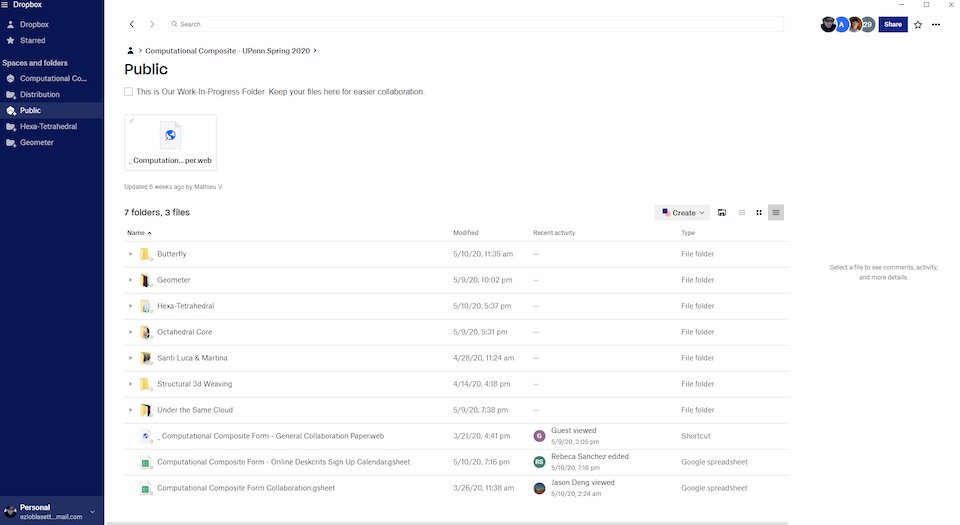

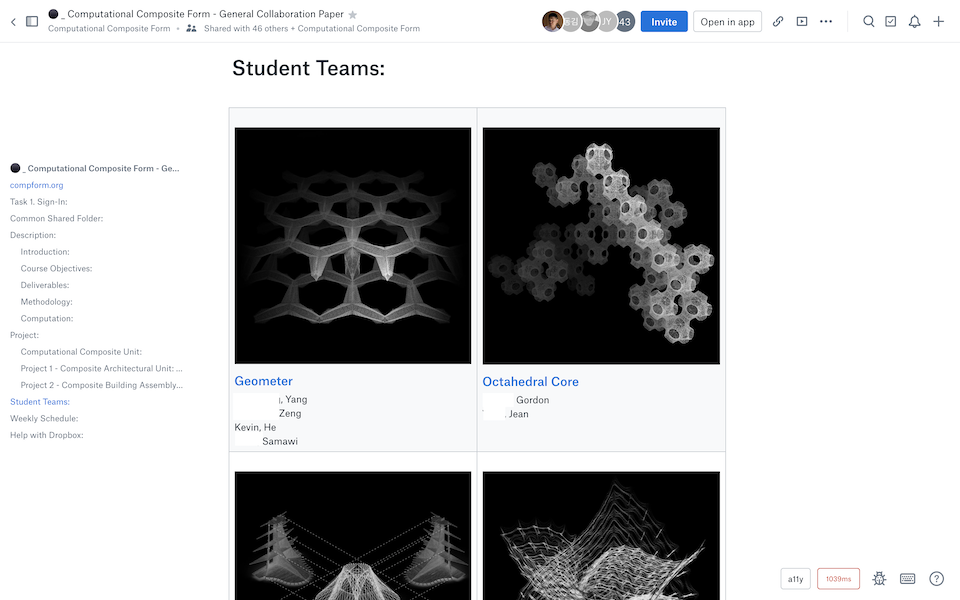

Blasetti has set his class up virtually, relying especially on Dropbox and Zoom. They have a dedicated Dropbox Space, serving as the hub for code, digital renderings, images, and other project files. Lectures and presentations run through Zoom and Dropbox Paper, where students present their findings and provide feedback to one another.

“Dropbox Spaces has been really helpful in keeping everything in the same place and organized,” Blasetti says. “I personally really enjoy the immediacy and transparency of the tool: the way you get notified anytime a student or a collaborator updates something in our shared project space. We're using it as an operating system for our collaboration.“

Then on April 24, Blasetti was granted permission to the retrieve one of the robots from the lab. He then set it up in his home studio with a camera, so his class could program and observe their work remotely. By uploading video files to their Dropbox Space, the class now has a proxy for in-lab working and real-time feedback on their fabrications.

“It’s funny, for our usual class we pin up a lot of drawings and post-it notes to start a discussion and get feedback,” says He. “Now we do a similar thing, but digitally. We can leave files in Dropbox Paper and it all previews so well, and then post comments.”

Keeping that collaborative, back-and-forth spirit alive has been a priority for Blasetti. “It's critical that people will learn by example and from each other,” he says. “If an experiment succeeds with one team, it quickly propagates throughout the class. We’re trying to cultivate an environment where that level of experimentation and sharing is encouraged, because this kind of research doesn’t work because of a single genius. It happens by putting different people with different ideas together, and I’m just glad that we’ve still been able to do that while not being in the same place.”

It was Victor’s intention all along to assemble this unconventional pairing of graduate students and a material innovation company. “Our creative technology transfer process aims to put cutting edge tools in the hands of fresh creative minds,” he says. “Young architects and students and artists are so open to experimentation, which can produce spectacular insights.”

A new model for working

This level of experimentation applies not only to the work itself, but the way of working. The Biennale is scheduled to open August 29, but isn’t a sure thing. No one knows when campuses will re-open. What we do know is that this distributed work and education model is the new normal for the foreseeable future.

“What started as a very practical, hands-on class has turned into a study about digital collaboration,” Victor says. “Schools and also companies are going to have this experience that when you're forced to work remotely, you realize the advantages of working remotely. It can be hard to get everyone together in person, even in normal times. But if you just have an open Dropbox Paper document, those people can get to that work on their timeline anywhere they happen to be. You actually end up building huge amounts of efficiency: instead of struggling to get people to sit down in meetings and pay attention, then go back to their desk, write up the action items, only for someone to send out a now-outdated Word document in an email—I think we’re all learning better ways because we’re being forced to.”

As Blasetti’s students are finalizing and selecting their designs this month, LeMond Composites (and the robots!) will be ready, whenever they get the green light on construction. Whether it’s in Venice or elsewhere, the team will eventually find a stage for their work. For now, all they can do is remain connected and adaptable. “It’s just a really bizarre period in our life,” says LeMond. “It's going to change the way people work and operate, re-thinking how productive they can be without having everybody in one place. We originally sought out to teach and learn about robotics and carbon fiber and the like—and that’ll come. But as it turns out, right now we’re learning the most about ourselves.”

For the latest on remote collaboration for higher education, check out Victor's next initiative, Digital Studio Project.