How farmers in Tanzania are using solar energy to invigorate their economy

Published on January 18, 2019

Despite its nickname of “Rock City,” Mwanza was built on water. Nestled on the shores of Lake Victoria, Tanzania’s second largest city is a bustling hub for trade, shipping, and transportation to otherwise inaccessible islands and villages across the country.

Within these villages lies the true rock of Mwanza and its surrounding area: farming. 85% of Tanzanians work in agriculture, with the lushness of their crops serving as the leading indicator for the wider economy.

According to a study by the Irish government, Tanzania experiences severe droughts with devastating effects to its agriculture, water and energy sectors. The Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) Index ranks Tanzania as the 34th most vulnerable and 54th least ready to adapt to climate change, of the countries it covered.

Simusolar is working to address these problems. The Mwanza-based organization produces solar-powered equipment for farmers to fundamentally change how they make a living.

“We told you the percentage of Tanzanians who are farmers, right?” says Arnold Mlokozi, a Mwanzan-born agronomist at Simusolar. “But of that population, only 2% have access to proper irrigation tools.”

We visited Mlokozi and his team to see firsthand the impact they’re making.

Mlokozi is our guide as we set out to see these farms in action. We’d be blind without him—Google Maps stopped working a long time ago. He leads us to a port to board a commuter ferry departing Mwanza.

Lake Victoria is massive. The rocks on Mwanza’s shoreline are soon specks in an endless horizon. When we disembark, we’re officially into the rural parts of Tanzania. There are no roads, few vehicles besides our clumsy van, but no shortage of energy. Virtually every adult woman carries goods in baskets expertly balanced on her head—even if her hands are reserved merely for waving to friends. Fishermen showcase their fresh bounty, igniting a marketplace that’d put a stock exchange to shame.

“It may seem chaotic to you, but there is a system in place here,” Mlokozi says.

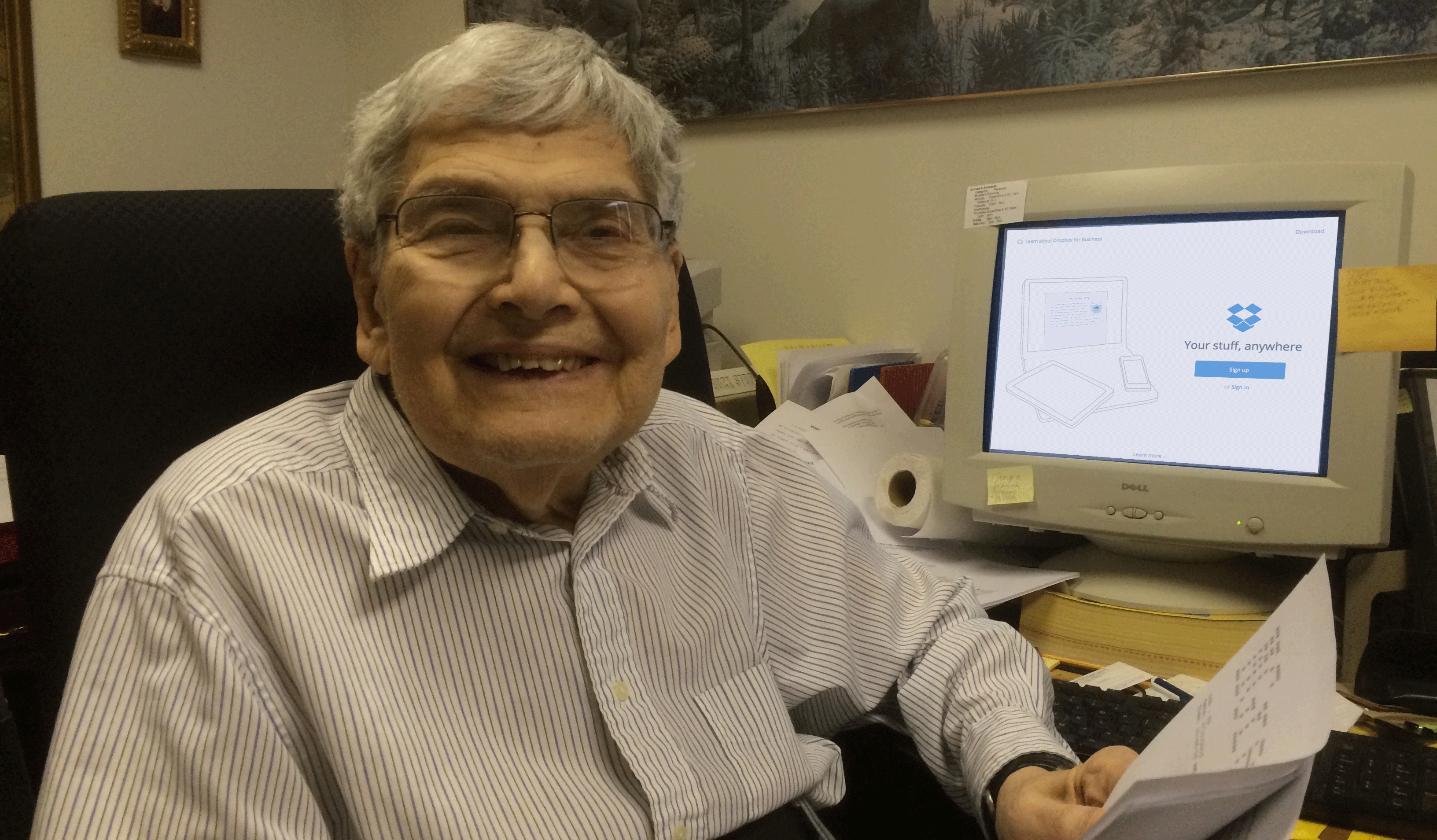

Hours of dirt-path driving later, we arrive at a quiet farming village. Mlokozi greets the farm owner and Simusolar customer, Venance Daudi. After catching up, Daudi looks through the latest market data and equipment updates through Dropbox on Mlokozi’s iPad. The seemingly jarring juxtaposition of modern technology and age-old craft is surprisingly natural. We observe as Daudi and his team power up the solar panels. The pumps generate a soft hum, with water effortlessly flowing over each row of produce. They’re done before we know it.

Things didn’t always run this smoothly, Daudi tells us.

“Before [Simusolar], it would take five hours to finish the job. It was tough, too much walking,” Daudi says through our translator, pointing to an old bucket he previously used. “Now after I get this pump, my life is easy. It now takes one and a half hours to do the job that took you five hours before.”

The impact goes far beyond just hours saved. Simusolar’s ultimate goal is to help change the economic model from subsistence farming—or providing food solely for one’s immediate consumption—to agribusiness farming. “We want our customers to produce at scale, with the intention to sell and make a profit,” Mlokozi says. The organization is also servicing fishers by providing energy-efficient lanterns, as the most productive runs come after dark. “Those fisherman you saw earlier were up all night, using our lights on the lake.”

He goes on to explain the domino effect. “With the agribusiness model, you’re a true business owner, increasing income for yourself and those around you. The bigger the farm, the more jobs created, the healthier our food. We hope that can stimulate the economy beyond this village.”

“It now takes one and a half hours to do the job that took you five hours before.”—Venance Daudi, Farmer in Tanzania

Simusolar is also not a nonprofit. They sell their innovative equipment, with creative financing plans for wider accessibility. “It’s important, culturally, that our customers pay for these tools,” says Mlokozi. “It’s part of being a business owner.”

And while the economic impact is immediately visible, the environmental benefit of using solar energy has long-term, permanent implications. Replacing existing kerosene-based equipment, at this scale, is a first step to a greener future for Tanzania. It’s also much safer for operators, as equipment-related fires were an all-too-common occurrence, Mlokozi tells us.

Mwanza and the surrounding area is home for Mlokozi. But when we ask him about what it means to be helping his community, on an emotional level, he remains pragmatic. He’s an academic at heart.

“We’re here to teach our customers about agribusiness farming,” he reiterates. “We want them to be able to produce no matter the season, without relying solely on rain. It’s better when they can diversify their crops, beyond just corn, to bananas, papayas, collards, cassava. When we can see the changes, we know what we’re doing matters.”

The change is right in front of us. We’re standing in the middle of three-acre farm—with sunflowers up to our chests—that was a quarter-acre plot of land just three months ago.

“My family and I are very happy for these changes,” Daudi says. “And we can keep growing.”

Since launching, Simusolar has helped almost 20,000 farmers and fishers increase their income and quality of life, when two-thirds of them were previously living below the poverty line. And the team has hopes of expanding their customer base throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

“We wanted to build something sustainable, something we can grow in Tanzania and grow elsewhere,” says Simusolar COO Michael Kuntz.

Our team needs to hustle back to Mwanza—the sun sets quickly near the equator. For the fishing community, the day is just starting. For Daudi and other farmers, they’re grateful the sun will be back up soon enough and that they’re able to harness its power—for “Rock City” and beyond.

To learn more about Simusolar, visit their website here.