This studio is cataloging ingenious contemporary African design

Published on September 01, 2023

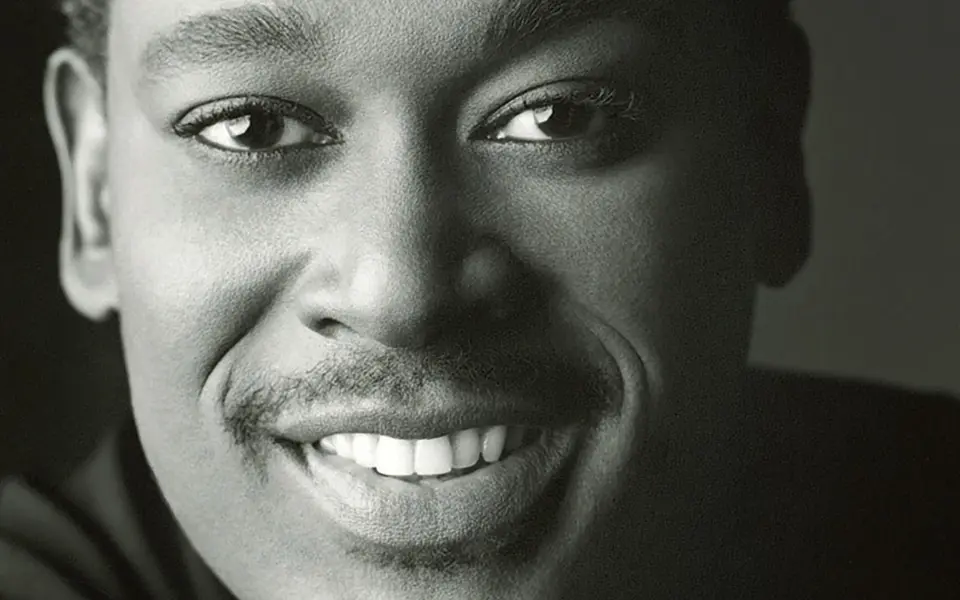

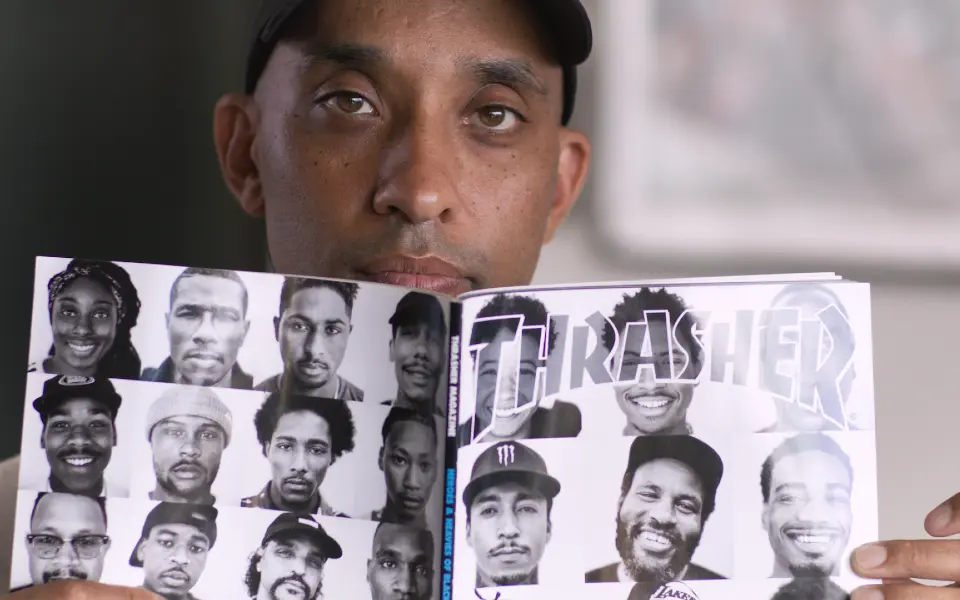

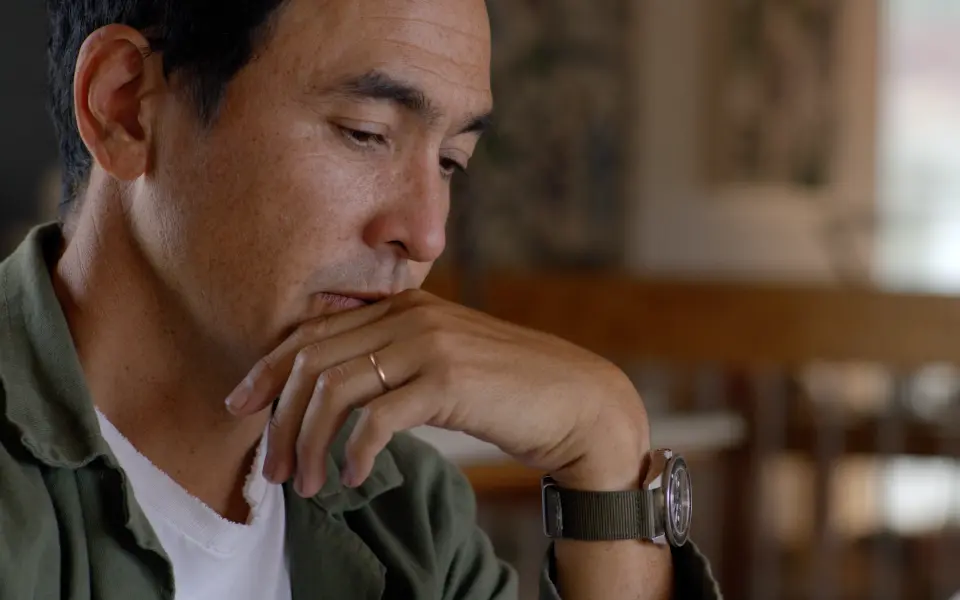

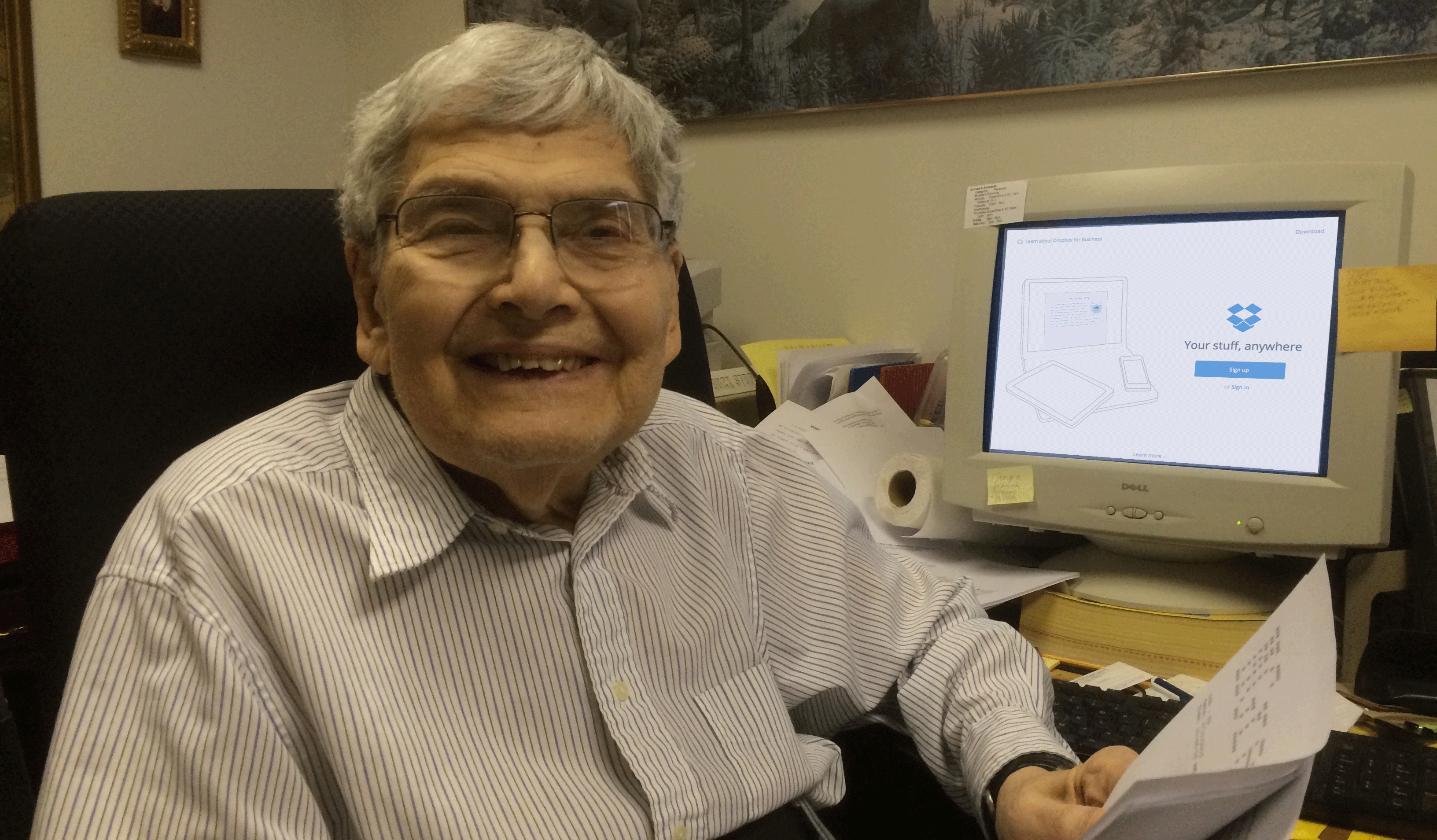

Designer Nifemi Marcus-Bello is creating an open-source archive of modern African design with support from collaborators across the continent and Dropbox.

When you hear the phrase “African design,” what comes to mind? Is it a large tribal mask hewn from mahogany and adorned with cowrie shells? A polished warrior figure with intricate patterns etched into its skin? Or maybe you’re seeing squat, one-story homes made from thick layers of mud and clay with thatched roofs.

Those examples are foundational, but design on the continent isn’t as frozen in time as our imaginations would have us believe, says designer Nifemi Marcus-Bello. You can see it in the modern skyscrapers and flats that make up its cities and in Marcus-Bello’s own work, like the LM Stool—a quietly modern piece he created by working with generator fabricators in his hometown of Lagos, Nigeria.

In fact, he argues, the world’s concept of African design should expand beyond what you’d see in a natural history museum to include the continent’s most quotidian objects—ones that are so indispensable, they’ve become invisible.

“A lot of the times, when design…is open source and can’t be traced to a certain individual or organization, it’s seen as something that just exists,” Marcus-Bello explains.

“But somebody had to design it,” he continues. “A community had to design it. Because of that lack of documentation, it’s always hard to trace who the real authors of certain designs or ideas or even technologies are.”

Marcus-Bello and his team at nmbello Studio have spent the last few years creating that paper trail with their research project, “Africa: A Designer’s Utopia.” The three-person crew is developing an open-source archive of contemporary African design on Dropbox—starting with Lagos, but with plans to expand across the continent through collaborations with photographers, videographers, and the artisans and laypeople who make these products.

"...if we didn't start documenting our history, someone else would and then dictate to us what it is that we should see as African design."

“Every major city on the African continent is unique, [from] way of life to material availability, so the objects differ,” he explains. “It is important to not only document objects that differ but ones that have similarities in functionality and character, with the idea to spark a cross-continental discussion of what design on the continent is.”

One such design is the kwali, a portable vending machine of sorts for vendors selling candies and snacks to people stuck in Lagos’ notorious bumper-to-bumper traffic. Made of styrofoam, tape, and cardboard, the kwali isn’t typically what you’d see heralded as great design worth documenting, but it is—and the context behind its creation is what makes it distinctly African.

Identifying and archiving contemporary African design is a massive undertaking, one that made it clear the team would need a tech solution that prioritized collaboration, organization, communication, access, and security—something their usual WhatsApp threads couldn’t offer.

“Before the idea of using Dropbox came along, I was actually a bit scared and skeptical,” he says now. “Without it, the research couldn't exist.”

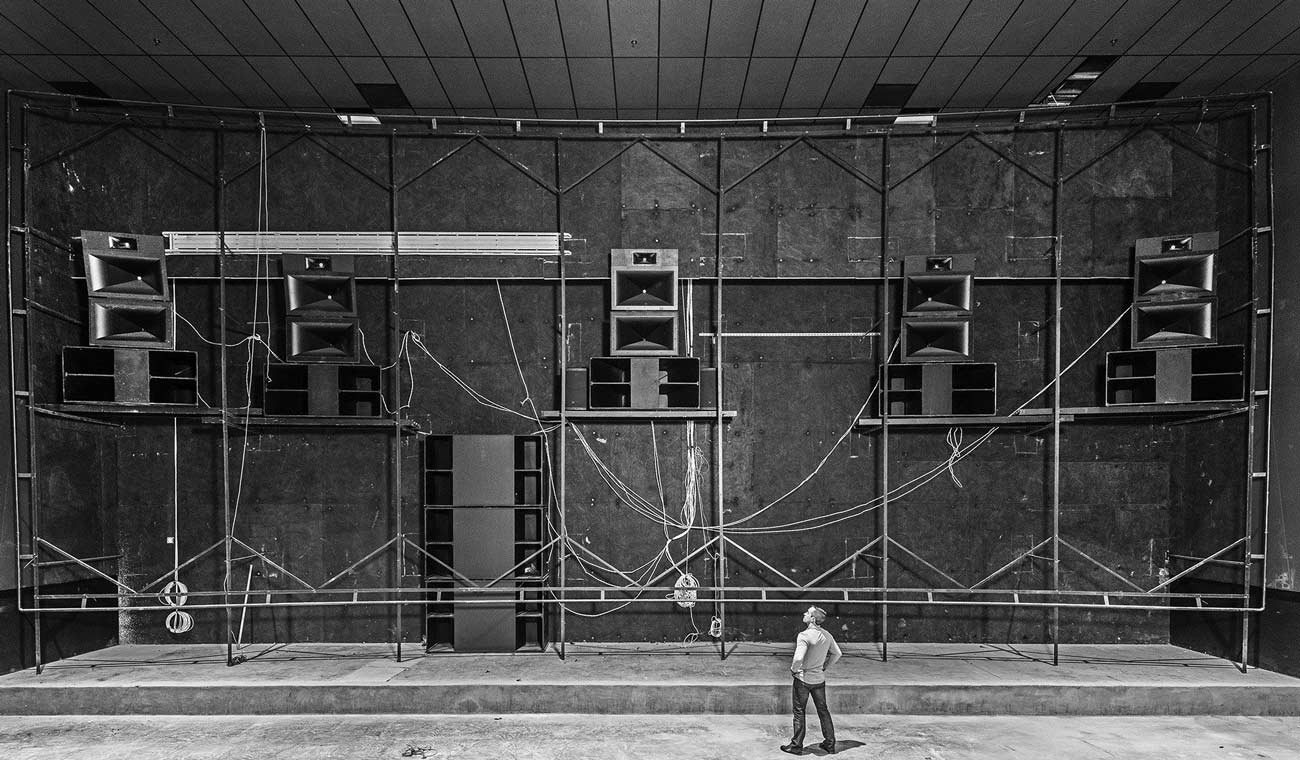

So far, the project has cataloged three objects. Marcus-Bello is preparing to share them at the Sharjah Architecture Triennial, an event that fosters discussions around design in the “Global South” through exhibitions, research, and panels, this Novembe in the United Arab Emirates. The award-winning designer spoke to Dropbox about how collaboration has created the archive and his cross-continental design language and approach.

You’ve said you wanted “to figure out what it meant to design in Africa in a contemporary way.” What did you mean by that?

The idea [for “Africa: A Designer’s Utopia”] was actually birthed from having conversations with friends abroad who were saying, "It's a shame that contemporary design doesn't exist on the continent. So how are you going to practice?”

I was a bit bummed. But then I realized, you know what? Maybe I need to open a third eye and figure out what it means to design here. I think the Western world has separated the practice of Art and Design, but the beauty of African creativity and African design is that it’s always been one.

I went to University in Leeds, up north in England, and the anthem there was the 10 Design Principles of [German industrial designer] Dieter Rams. So what I did was take those principles and put it against an object. Once I looked at both the principle and the object side by side, I was like, “Yo, this falls under every single category theory of what good design should be, even though this doesn't have a designer tag to it.”

Rams [also believed] design should always be in the background, extremely quiet. But for us on the continent, design has always been in your face and extremely obtrusive. It’s everywhere. Like a stool can be very functional, but then have ornaments at the bottom that speaks to an artistic approach. Same thing when it comes to architecture. So for me the beauty of African design is the context in which it’s being practiced. Design in Lagos is different from design in Accra—leaning on availability and resourcefulness.

I realized that if we didn't start documenting our history, someone else would and then dictate to us what it is that we should see as African design. From there, [we] started taking images … of some objects across Lagos on [our] phones. Then it started moving into taking videos of people actually making these objects locally, and uploading it all onto Dropbox.

What are the three designs you’ve found so far?

The kwali: That product is basically birthed via urbanization—people coming from other parts of Nigeria to find jobs [and] then setting up businesses for themselves and creating these kiosks out of readily available materials. And these materials are available via globalization because goods [get] brought into Nigeria, the packaging is thrown out, and these guys pick it up to create products.

There’s the meruwa, a portable device that transports water from one place to another—because of the lack of water suppliers across Lagos, a lot of homes are supplied through these water pushers. The other one is the orika setup. I always joke that it’s an architectural marvel because they use wood cut offs and nail them together to create high, high stilts where they hang these bootleg streetwear T-shirts, and then they create handles to handle the T-shirts.

With your designs, it feels like you’re creating a new language that didn’t exist before between designers and artisans, laypeople, manufacturers, and distributors in Lagos.

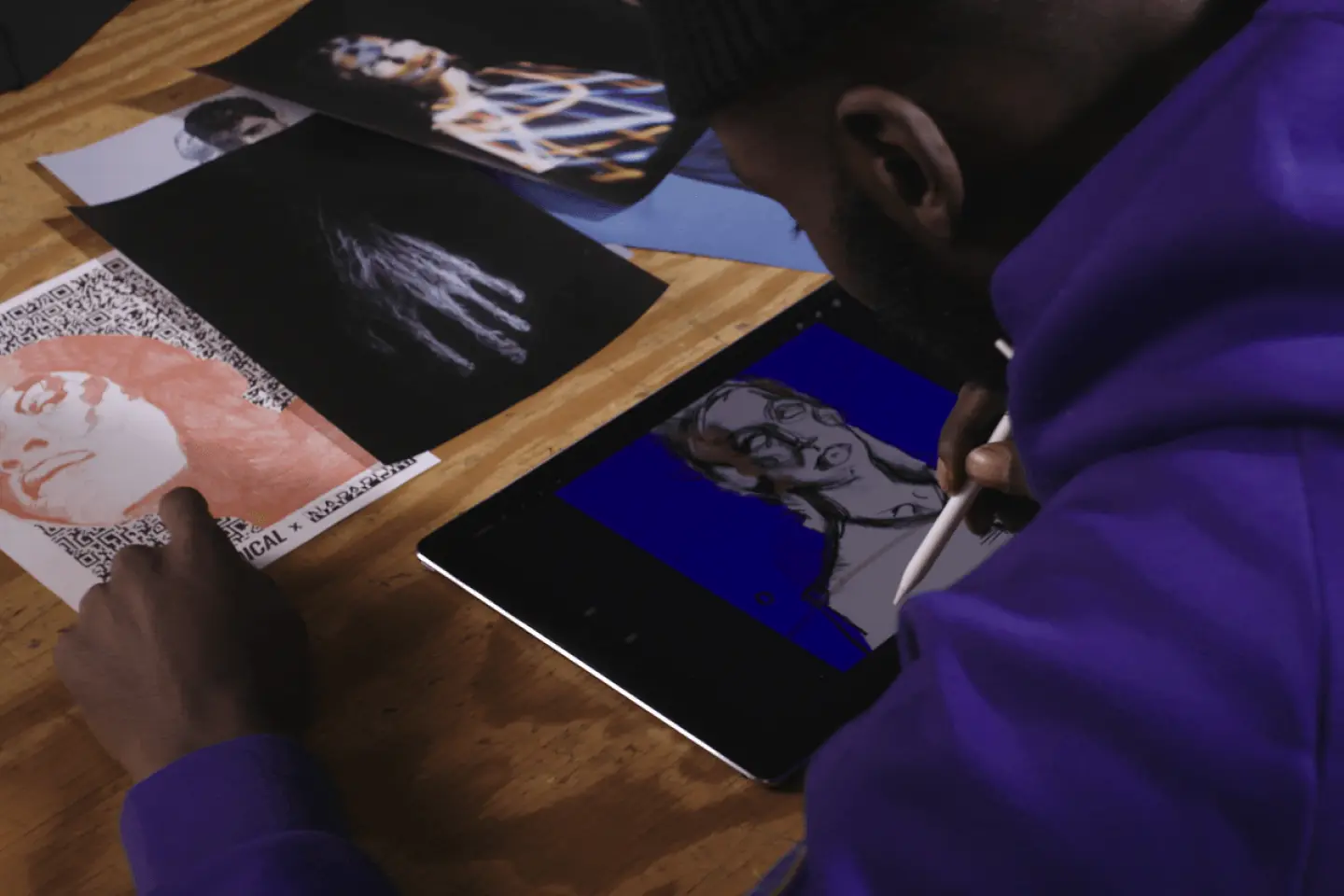

One thing I’m proud of is the fact that I do have intimate conversations with artisans on what it’s like to practice contemporary design. I educate them that they can be designers too and there’s that knowledge exchange of them also educating me.

A lot of times I get things made across Lagos—I don’t really have a personal workshop. With a lot of the nooks and crannies of Lagos I go to, I can’t take my laptop with me. I'm never an outsider—because I'm a Lagosian through and through—but in some instances, I do not want to come in dictating with crazy technology or anything that will kind of stifle conversations. Everybody has a smartphone. So when I'm dealing with artisans, I can literally go on my phone, go into my Dropbox, and get the drawings that I need. Without Dropbox, it seems impossible to practice effectively.

I remember interacting with a welder, Mr. Fatai, who I’ve known for years—since I was a teenager. One day, we were having a conversation after I showed him a sketch. He wasn’t really getting the idea. I remembered the night before I had uploaded the drawings to Dropbox, so I showed him a drawing. He was able to get the right dimensions and detailing needed to finish up the piece.

"[Dropbox has] actually opened my mind to the fact that you can build a team across the continent."

Another African proverb you’ve used is that you can go farther as a collective than by yourself. Cross-continental and cross-experience collaboration is a big part of what you do. What does that look like in practice?

You know, the research is called “Africa: A Designer's Utopia” for a reason. I think the best thing about practicing here is that…you're basically figuring out a way to exploit—not just the materials, but the coming together of designer, maker, distributor to [reach] an end goal.

[So] yes, the studio can drive this project, but it really does have to be open source—we need as many hands on deck as possible. One of the things that was important, especially at the early stages, was figuring out the best way to use the right communication tools. To not just communicate the idea, but to also document findings.

Because I really wanted this research to be collaborative and done properly, I started reaching out to professional photographers and videographers. They have access to the folder and they’re just uploading themselves. They’re all based in Lagos now, but I’m speaking to a photographer in Dakar for the next chapter of the research project and I shared the Dropbox link with him recently.

I’ve had a studio manager who’s now remote who I’ve only met once and is in Nairobi. She uses Dropbox as much as we do. It’s actually opened my mind to the fact that you can build a team across the continent, and not have the person right next to you. That has changed the dynamic and the exploration of adding new members to the team.

I always used to say, "Oh, there's only two or three people within my studio." But I was having a conversation with an elder, and he said something fantastic. He said, "Yo, you can't say that, because you've basically built a community and your studio is a community—and these artisans are part of your studio." It made me feel like I was getting closer to questions I have been posing to myself around design ecosystems on the continent.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

See how a kwali gets made.

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/SH-06003_R%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(2).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/1200x628%20(5).webp)