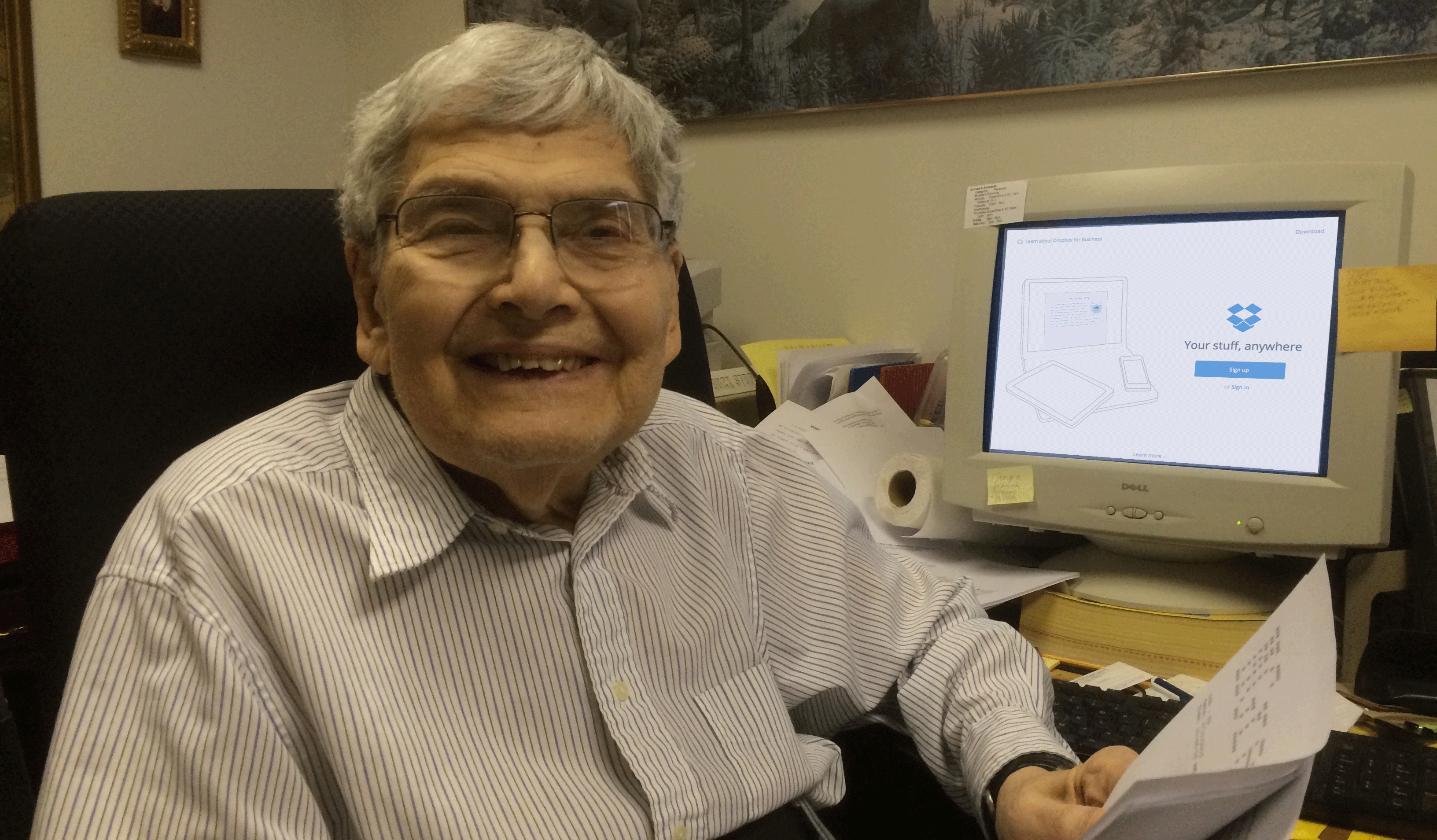

How one forensic psychologist keeps private investigations private

Published on April 12, 2024

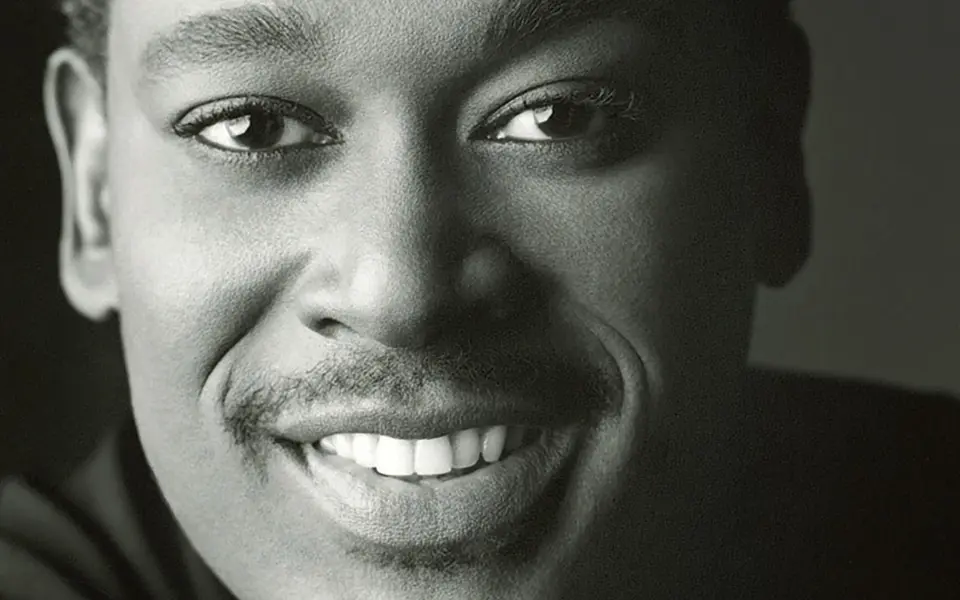

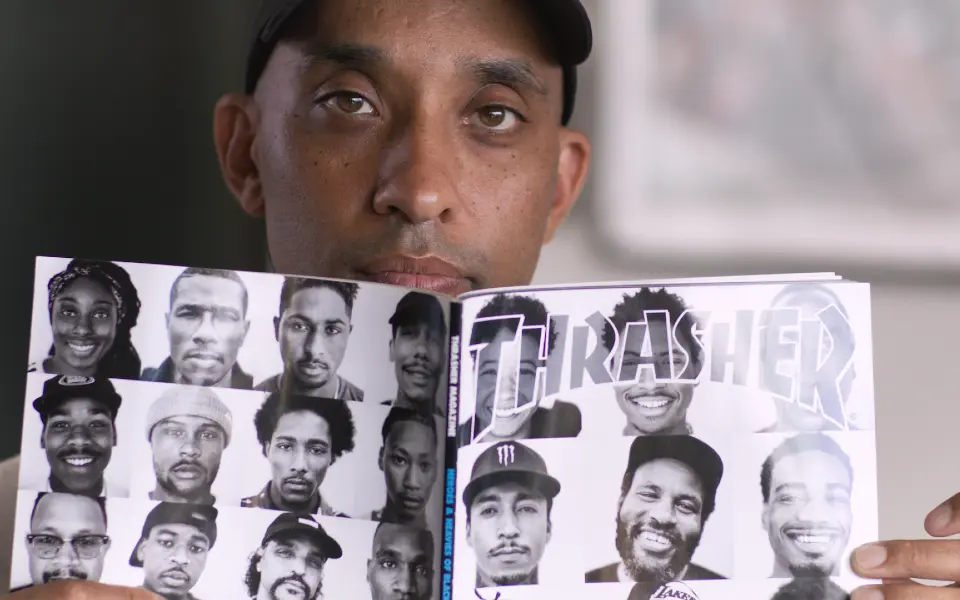

Using Dropbox and Dropbox Sign, Dr. Leslie Dobson protects confidential content, catalogues every clue, and uncovers details that solve true crimes.

When you’re an empath with an extraordinarily strong BS detector, red flags are hard to ignore. Even as a child, Dr. Leslie Dobson had an intuitive sense for when someone was hiding the truth.

“I could always see the elephant in the room,” she recalls. “I noticed adults ignoring immoral behavior, and it drove me insane that people would shove stuff under the rug. I always had this voice in me and a desire to figure out a way to use it—psychology helped fulfill that.”

After earning M.S., M.A, and Psy.D degrees, Dr. Dobson went on to establish her private practice as a clinical and forensic psychologist. She provides evidence-based clinical intervention for those who’ve experienced trauma. Lawyers also tap her to provide assessments for their civil litigation and personal injury cases.

“I come with all of the experience of knowing what’s in the mind of a criminal,” she says. “Then I can work with the victim and help them understand what they went through.”

But even someone trained to spot lies can fall prey to scams and predators. Recently, Dr. Dobson was the victim of an email hacking incident that prompted her to double-down on security. She turned to Dropbox to safeguard a truly massive amount of confidential information—and started using Dropbox Sign to collect e-signatures on the mountains of documents she handles.

“A lot of my reports need to be very quick. We can't wait for the mail, so I’ll get approval from attorneys or the legal system to do online signatures,” she says. “I was using things like PDFfiller to put in signatures, then slowly realized I'm using too many tools when I can just go to Dropbox and do it really easily.”

In addition to being a therapist, forensic psychologist, speaker, and content creator, Dr. Dobson is now the author of The Friend Cleanse, which offers tips on identifying energy vampires—the people in your life who take more than they give. We spoke with her to dig into the reality of true crime investigations and find out how technology is helping her keep confidential content secure.

“I slowly realized I'm using too many tools when I can just go to Dropbox and do it really easily.”

As all armchair detectives know, you’ve got to wade through a swamp of details to find the clues that can crack a case. Could you pull back the curtain on what it really takes to navigate an investigation?

Initially, I get flooded with a ton of documents that pertain to the case. First, I have to get the documents very linear. So if we're looking at 50 years of medical records, and they're handwritten—upside down, totally disorganized—I have to organize everything. Then I usually summarize extremely lengthy depositions or stories into different files.

Then I take thousands and thousands of documents and write a [20-40 page] report incorporating all of them. I go through the report, making sure it sounds linear, and that we get to a mental health diagnosis that doesn't surprise anyone. The story should lead up to the diagnosis with all my psychological testing and evidence, and then *my* reward is to testify in court and share that document, explaining the truth to the court.

What’s your process for keeping all those documents organized?

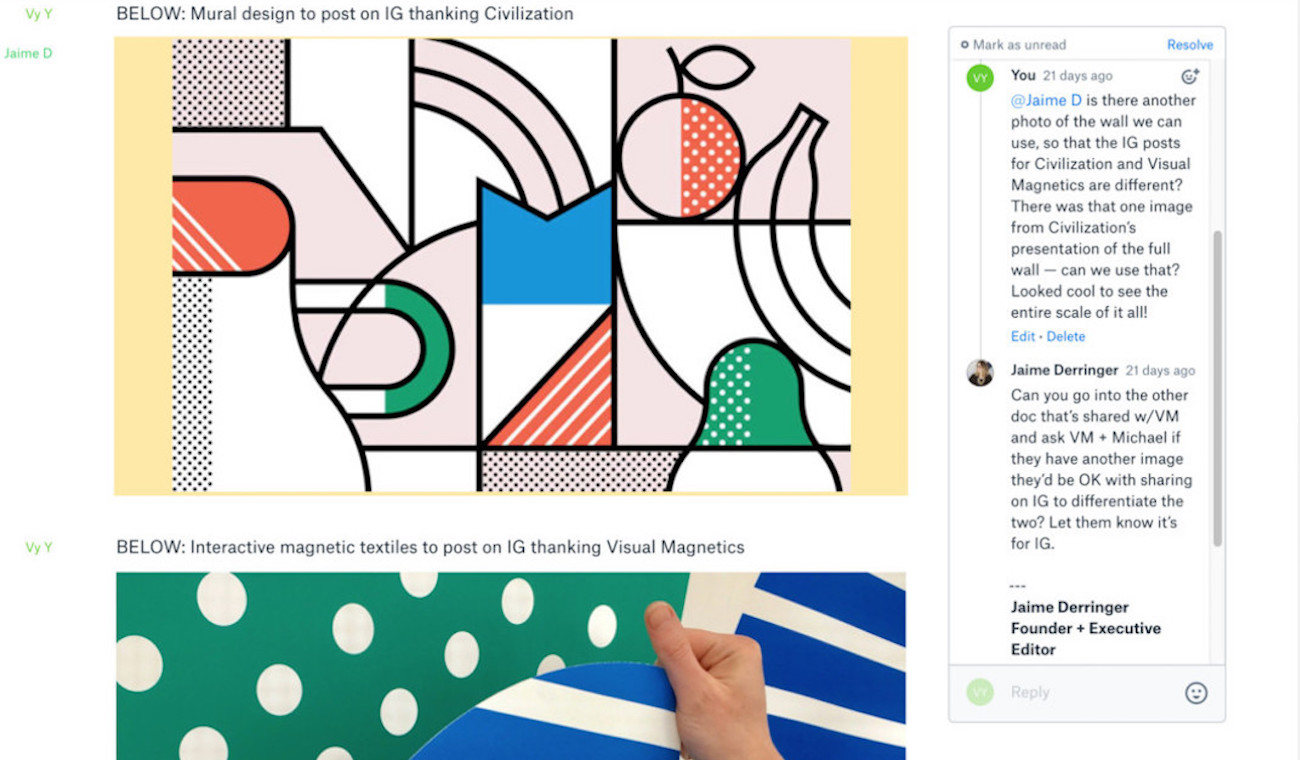

I have two assistants who help me. As we work towards an evaluation and a report, I upload what's needed. Then we break down my folders by each case and share different Dropbox links with different attorneys, according to who needs what. For example, psychological assessments can only be transferred to another psychologist, so I have a separate link for them.

It has been wonderful to be able to organize the data so I can stream through it really quickly—because it can get very convoluted when you have 10,000 records sent to you in one day.

How did the experience of being hacked change your approach to privacy and security?

I've focused much more on having phone calls about how we initiate file transfers. Then, when they are initiated, we’re very careful about who gets what link to what data. I've also upped all of my software security. I changed my cell phone and changed anything where my IP address may be followed. And of course, two-factor authentication. My assistants and I have passwords and code words that only we would know.

I'm involved in a lot of high profile, legal issues with celebrity cases and people that are billionaires, and they can hire hackers. They can try their best to figure out what I'm writing, what documents I have access to, and try to stop me from testifying. Dropbox prevents me from having to use emails—which are a lot more [vulnerable to hacking]—and [lets me] grant access to very specific people and limit who can view each document.

After 20 years of evaluating the mental disorders of some of society’s most dangerous people, you shifted your focus to helping first responders, veterans, and victims of traumatic abuse. What does that look like?

With first responders, it's very important to maintain linear documentation about past traumas that are work related, as I’m often called into be an expert for police or fireman in litigation. In my current practice, I no longer have the government providing me with documentation and organization. I’m on the line for everything as an independent practitioner, which makes security and organization even more important to me.

“It has been wonderful to be able to organize the data so I can stream through it really quickly... it can get very convoluted when you have 10,000 records sent to you in one day.”

Of all the tasks you have to manage, which one do you enjoy most?

I love the investigative work. What pains me is that people make so many assumptions about medical and mental health based on a 10-minute visit, and then that visit gets taken all the way to a trial. We put so much significance on a diagnosis where they didn't even get to know the person.

That’s why I like to siphon through everything and look at the minutes of the visit. When was the note signed? When was the note initiated? Is the person licensed? How long have they worked there?

I look at dates, medical or mental health symptoms, relationships, patterns in behaviors and timelines, length of doctors visits and diagnoses, treatment recommendation and follow up, presentation at appointments, texts and emails, collateral information, social media—anything and everything available to me to tell the story of the person in the most honest and objective way.

That's the kind of stuff I need to do to find the credibility of each document and source.

Is part of the appeal trying to solve the puzzle—seeing clues and details other people overlook, then connecting those into a larger story?

Very much. It's the puzzle of all of the records we're reviewing. But then, it's the puzzle of what testing instruments can I put together to demonstrate the validity of somebody's personality and their claims. For example, if someone is claiming to have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), I will gather evidence-based scientific assessments that help me objectively see if the person is trying to look overly symptomatic or trying to look healthier than they are, compared to normative samples.

A lot of my assessments are based on prior records of a person’s life, such as educational and medical records. Then figuring out how do I put it all together to bring it down to a sixth grade educational level in case someone on the jury never went to school. So it's this massive storm that ends in this light sprinkle.

Have to ask: What are your favorite true crime podcasts?

I love the cases where we don't really know what happened—these cold cases that are being picked up. I have my own cases that I've referred to the FBI that have been picked up as cold cases. If I get somebody who seems like a serial killer, I get to interact with the FBI. So if I find a podcast that is realistic, I love it.

Most recently, I've been listening to The Rise and Fall of Ruby Franke. That’s just so disturbing. I also loved Serial. I felt really connected to the Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo case about Kristin Smart, [editor’s note: discussed in the podcast Your Own Backyard] because I taught there and used to walk by the dorm where she was kidnapped or murdered.

Taking into account everything you’ve learned over the past 20 years, what advice would you give to someone who wants to get into forensic psychology in 2024?

The biggest thing I would do now is, start documenting every day. Start a journal on Dropbox. Put your thoughts and experiences somewhere you can remember. Because not only will those be incredible stories later, but the progression of your mind and maturity and confidence as you meet people in this field over 20 years is indescribable.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(2).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/1200x628%20(5).webp)