The road to ‘Spencer Pride’: How two filmmakers are telling a story of hometown heroes

Published on June 27, 2024

With the help of Dropbox Replay, indie documentarians are chronicling the success of Spencer Pride, a community center dedicated to improving the quality of life for rural LGTBQ+ people.

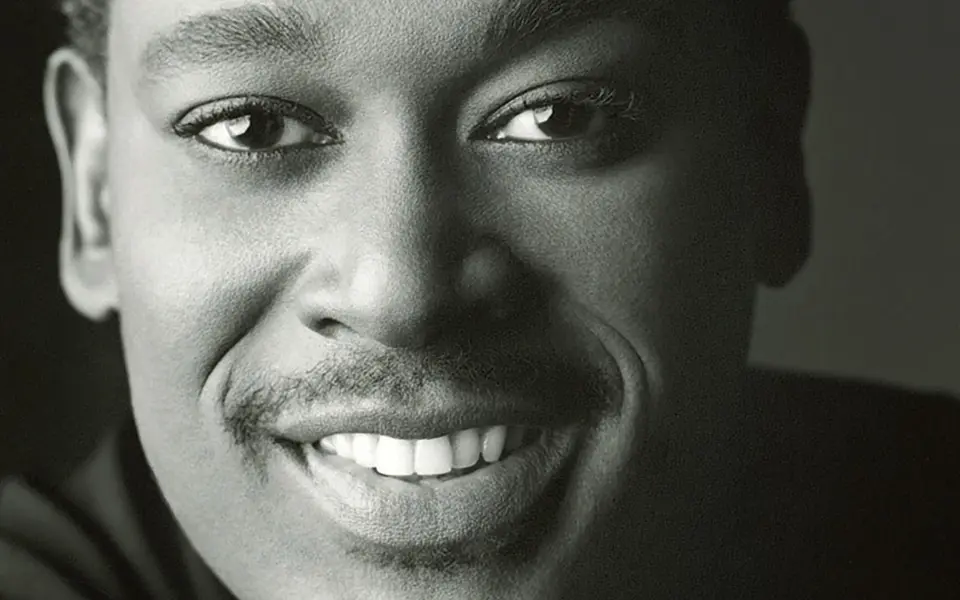

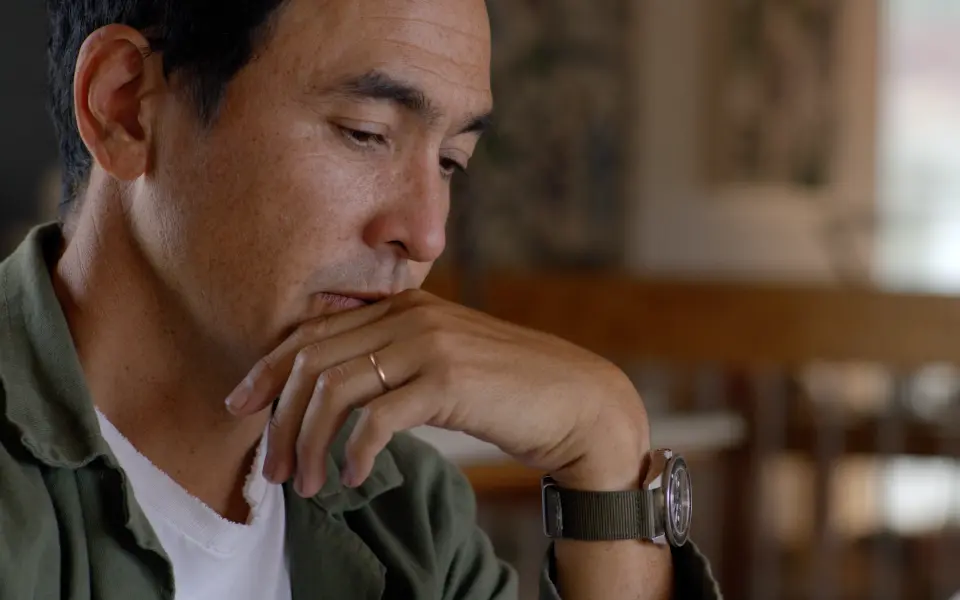

Documentary producer/director Mitch Teplitsky and his wife were on a Sunday drive through the small, southern Indiana town of Spencer in 2019 when they noticed a rainbow flag. And not just a 12x8-incher stuck in a front yard.

“A big, obvious one, hovering over the courthouse square,” Teplitsky recalls. “I’m like, What’s going on here?”

Interest piqued, Teplitsky stopped his car to learn more. Turns out the flag wasn’t just honoring Pride Month. It represented the year-round work of the Spencer Pride commUnity center. Since 2007, the SPCC has hosted events supporting, celebrating, and advocating for the queer community in the town of 2,466 and in rural Indiana at large.

“We established Spencer Pride because our rural community needed resources. Six of us got together and set our mind to filling that gap,“ explains SPCC president Jonathan Balash. “The choice to do this in Spencer wasn’t strategic, it was organic: We did it here because this was our home.”

Originally an annual festival, Spencer Pride added LGBTQ+ History Month events in 2010. In 2016, they jumped at the opportunity to rent a space downtown to host year-round programming. Within 16 months, the SPCC had already outgrown its first home and bought a larger property on the square. Today, Spencer is recognized as the smallest town in the U.S. with a dedicated LGBTQ+ center.

“People often underestimate small and rural communities, and they underestimate their own ability to make profound change,” Balash says. “On multiple occasions, I’ve been told that our work has literally saved lives.”

Teplitsky knew he’d stumbled onto a fascinating story. Once back home in Bloomington, Indiana, he couldn’t help telling his friends.

“People from the coasts and cities were like, Oh my God, I can’t believe there’s a place like that there!” he says. “I could hear there was genuine curiosity.”

And when a compelling story meets genuine curiosity, there’s a documentary to be made. Today, years after that fateful car ride, Spencer Pride is in production, and telling a much bigger story than Teplitsky imagined, with the help of Dropbox and Dropbox Replay.

Small town, big story

After that first visit, Teplitsky was soon taking the IN-46 W back to Spencer. It happened organically, he says. He liked the folks at the center and was making friends in town.

“My favorite thing to do—maybe the thing I’m best at—is having conversations with people,” Teplitsky says.

Each trip and chat added more nuance. Turns out, while surrounding towns were on the decline, Spencer was thriving thanks to unlikely alliances the SPCC was fostering between LGBTQ+ locals and allies, including conservative citizens.

At a time when culture wars dominate the news, the commUnity center’s success is something local town officials and business leaders celebrate. In Spencer, despite differing political views, Hoosiers were fostering unity in one of the nation’s most conservative states.

“People from the coasts and cities were like, I can’t believe there’s a place like that there!” —Mitch Teplitsky

Teplitsky went back to New York to visit Peter Gould, an ailing friend who’d helped him fund his first film. He told Gould everything he was learning about Spencer. The retired old-school New York City conservative lawyer “planted the seed for the story,” Teplitsky says.

“We didn’t have the same politics, but we respected each other and shared anxiety about the country getting so divisive,” he explains. “He said, ‘If you could tell a story about ordinary Americans getting along to make their town better, I’d be interested. We need these kind of stories.’”

Gould funded the film’s initial research before he passed. Teplitsky returned to Indiana and hired a videographer to help record interviews. At the same time, he was drumming up an audience of supporters and got a spot on a panel at Indiana University’s Center for Rural Engagement. Would he be able to show a little bit of the project to the audience?

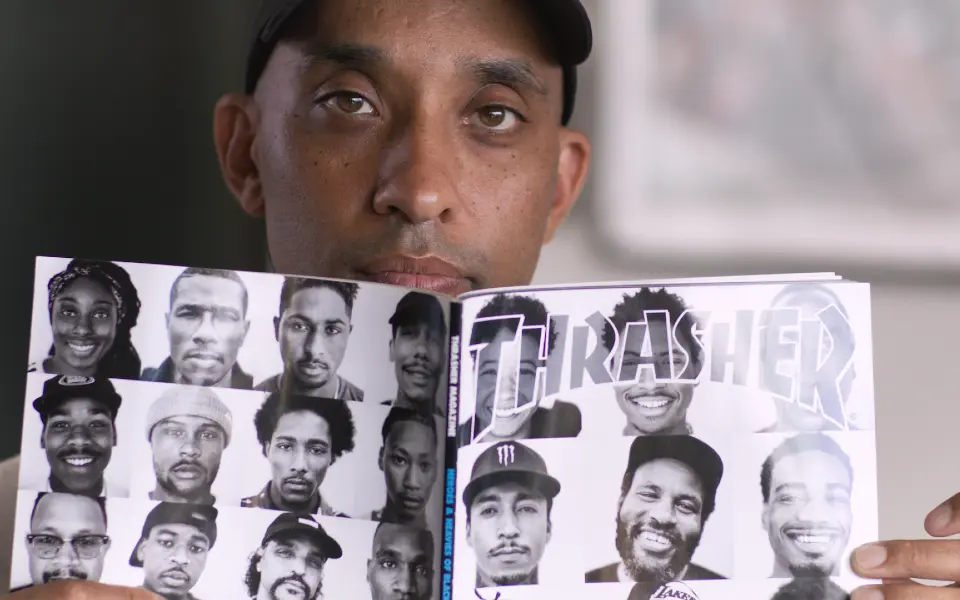

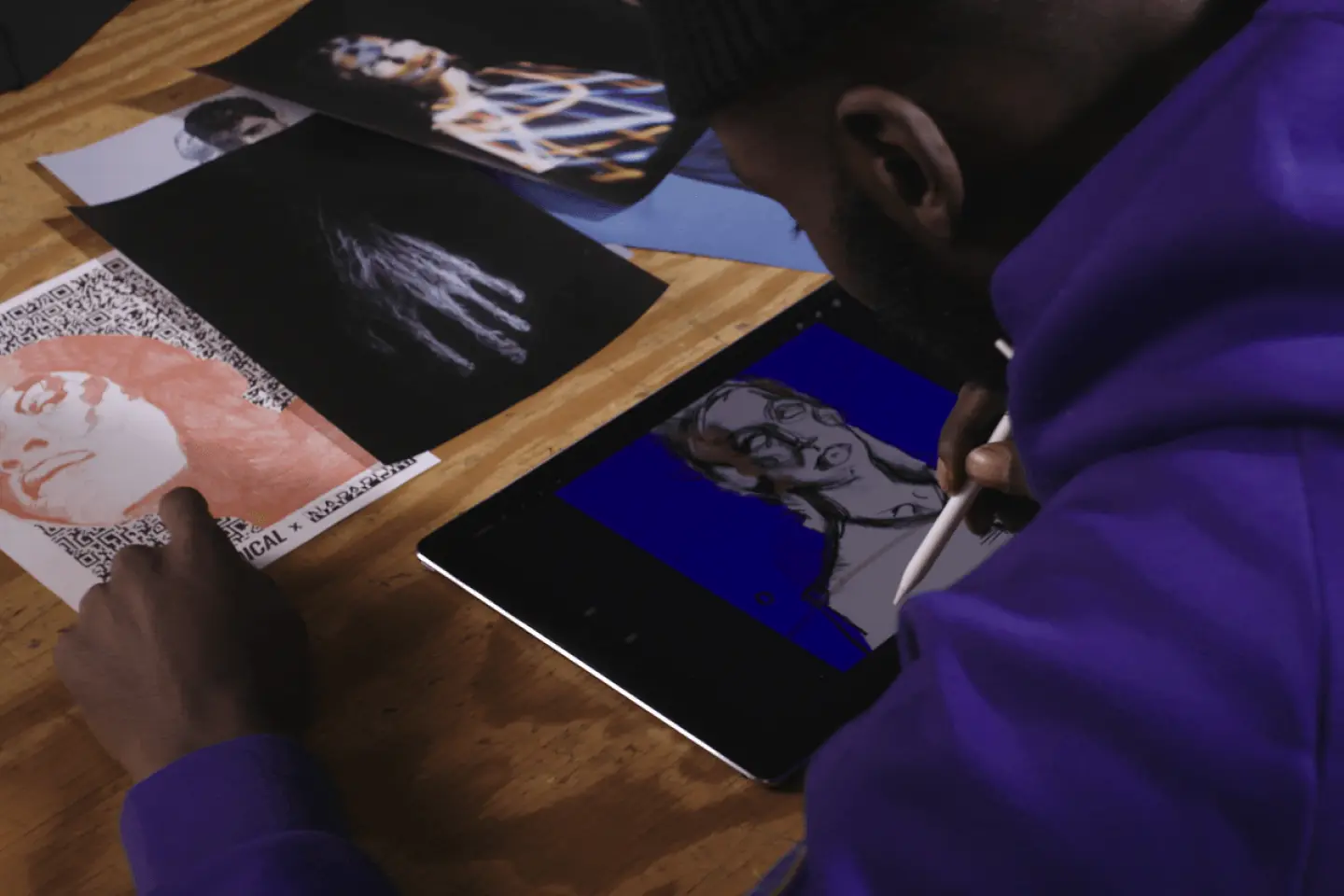

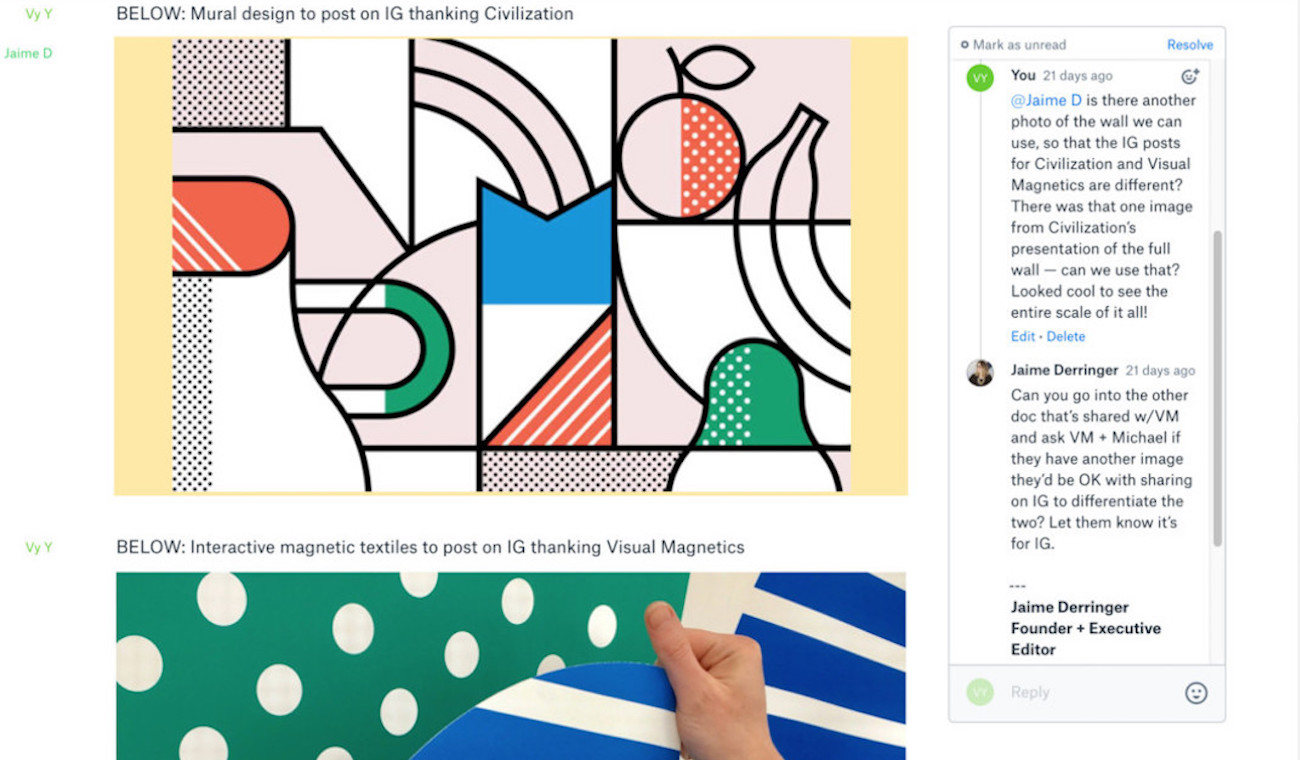

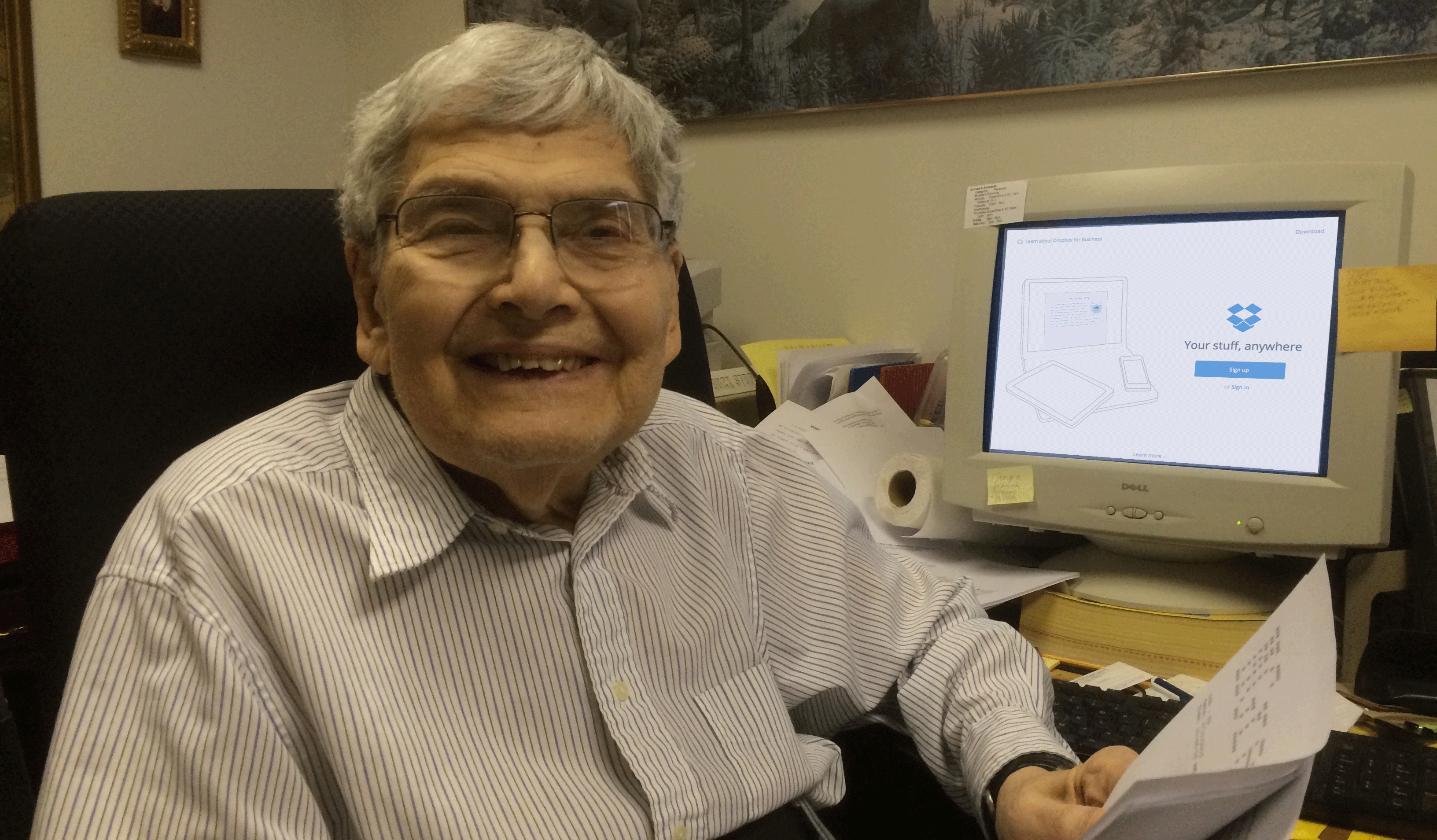

With several unlogged hours of interviews stored in Dropbox, he needed a video editor to distill that raw footage into something that conveyed the project’s essence. So Teplitsky tapped someone he had met through the local creative professionals scene, “multi-threat video content creator” Charles Pearce.

Pearce, who grew up in Bloomington, “kinda knew Spencer, but I’d stop at the McDonald’s, then keep going.”

“We were talking and reviewing footage,” he continues, recalling the first edit meeting, “and what jumped out to me was how clear there was a cinematic storyline. It’s been a long time since I’ve seen [an early project] and it just hit so good. You gotta jump in when you see something like that.”

Breaking the rules of traditional filmmaking

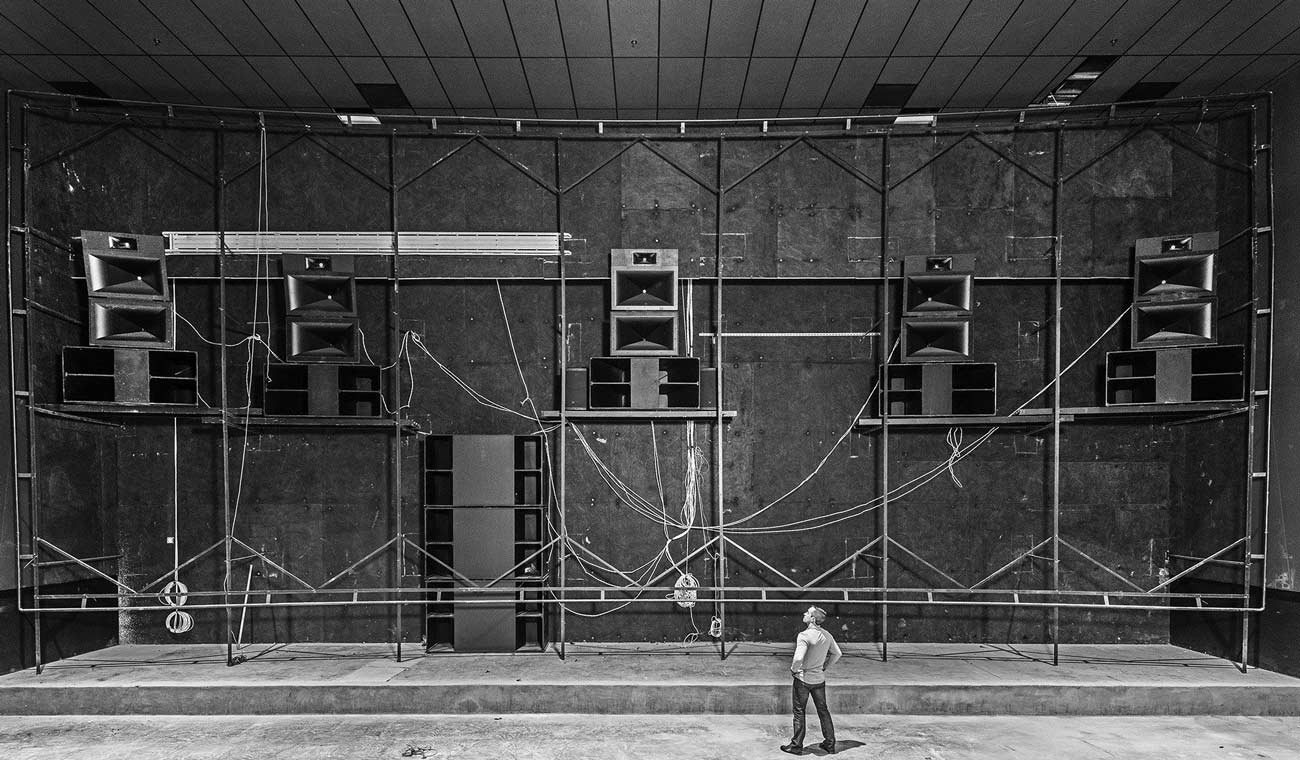

With Pearce on board as the film’s creative director, the two took stock of their strengths. Pearce owns his production equipment, so they didn’t need to hire a crew. And Teplitsky—“one of the best interviewers that I’ve ever met,” Pearce says—had become immersed in the community.

Pearce realized they would need to “break a lot of rules” bigger films and traditional indie filmmaking follow. Some moments happen on the production’s schedule, in front of Pearce’s high-end cameras; others Teplitsky captures with his iPhone during off-the-clock visits to Spencer.

“We try really hard to be nimble,” Pearce says. “So we’re thinking a lot about technology and tools—either [they’re] adding to our workload or making things easier.”

While he used Frame I/O for client work, Pearce knew Dropbox Replay would be a better fit for Spencer Pride.

“[Replay] provided a lot of clarity on how we think about the form of the film and the production that happens behind it.”—Charles R Pearce

“Frame I/O is okay if your only issue is getting comments or showing iterations, but asset management and attaching metadata to that assets… It doesn't do that very well. And it's really expensive,” he explains. “Sometimes the client project can justify that really expensive tool. But when it's out of pocket, costs versus features starts to become a much more granular equation.”

With hours of interviews and clips from different sources already stored in Dropbox, Replay’s file management system tipped the scale for the team. Teplitsky can upload material from Spencer from his phone to Dropbox, and Pearce, back at his basement office in Bloomington, can put it in Replay.

“I can do all of it in one house instead of six different siloed compartments of software where you have to do these elaborate referencing links between things,” he says.

Replay’s commenting system became an extension of Teplitsky and Pearce’s texts, phone calls, and emails. Then there were the unexpected delights of Replay’s transcription feature (clutch for “searching through all these volumes and hours of footage”) and thumbnail editor, so he can change out a still for one that provides more context as to what the clip is actually about.

“It’s provided a lot of clarity on how we think about the form of the film and how we think about the production that happens behind it,” Pearce says.

Doing the work of a full crew as a team of two

When asked about what’s next after Spencer, Teplitsky demures. His first film, Soy Andina, took him six years to make instead of the “few months” he had estimated at the time.

“The thing that's blown my mind the most on a day-to-day level is just how far we're going, as two people, when this used to be very large team work,” Pearce says. “It means that the story gets to evolve in real time as we're going. And that's been a lot of fun… To be able to go, ‘We’re talking about the Pride Fest from last year. We have photos from that. Here’s the folder.’”

Filming and production for Spencer Pride is ongoing, alongside fundraising, marketing, and finding potential distributors.

“[As filmmaker] Mark Duplass said several years ago, ‘The cavalry ain't coming,’” Pearce says. “You have to do a lot. It’s part of the business now.”

Part of that has been showing people what they already have, sometimes by opening the Dropbox app on their phones when they’re traveling or attending networking events, and sometimes back home in Indiana.

Last month Teplitsky and Pearce returned to Indiana University’s Center for Rural Engagement conference. The duo shared 11-minutes of sample footage from the documentary with the audience.

“There was an energy in the room,” Teplitsky says. “We just had this great conversation. Actually, that’s what I love the most. If after watching something, they wanna talk about it and share their experiences [with] me, that’s success.”

To learn more about the Spencer Pride film, check out spencerpridedoc.com.

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(2).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/1200x628%20(5).webp)