Let There Be Neon helps artists create truly electrifying work

Published on January 11, 2023

The New York City-based fabricator relies on Dropbox to collaborate with artists who want to create with neon.

When you think of neon, your mind probably conjures up bright lights adorning big businesses in even bigger cities.

It’s been that way since 1910, when French inventor Georges Claude first harnessed the commercial possibility of merging neon gas with electricity and glass tubing. Since then, neon has lit up storefronts, clubs, and eateries, attracting patrons like moths to a flame.

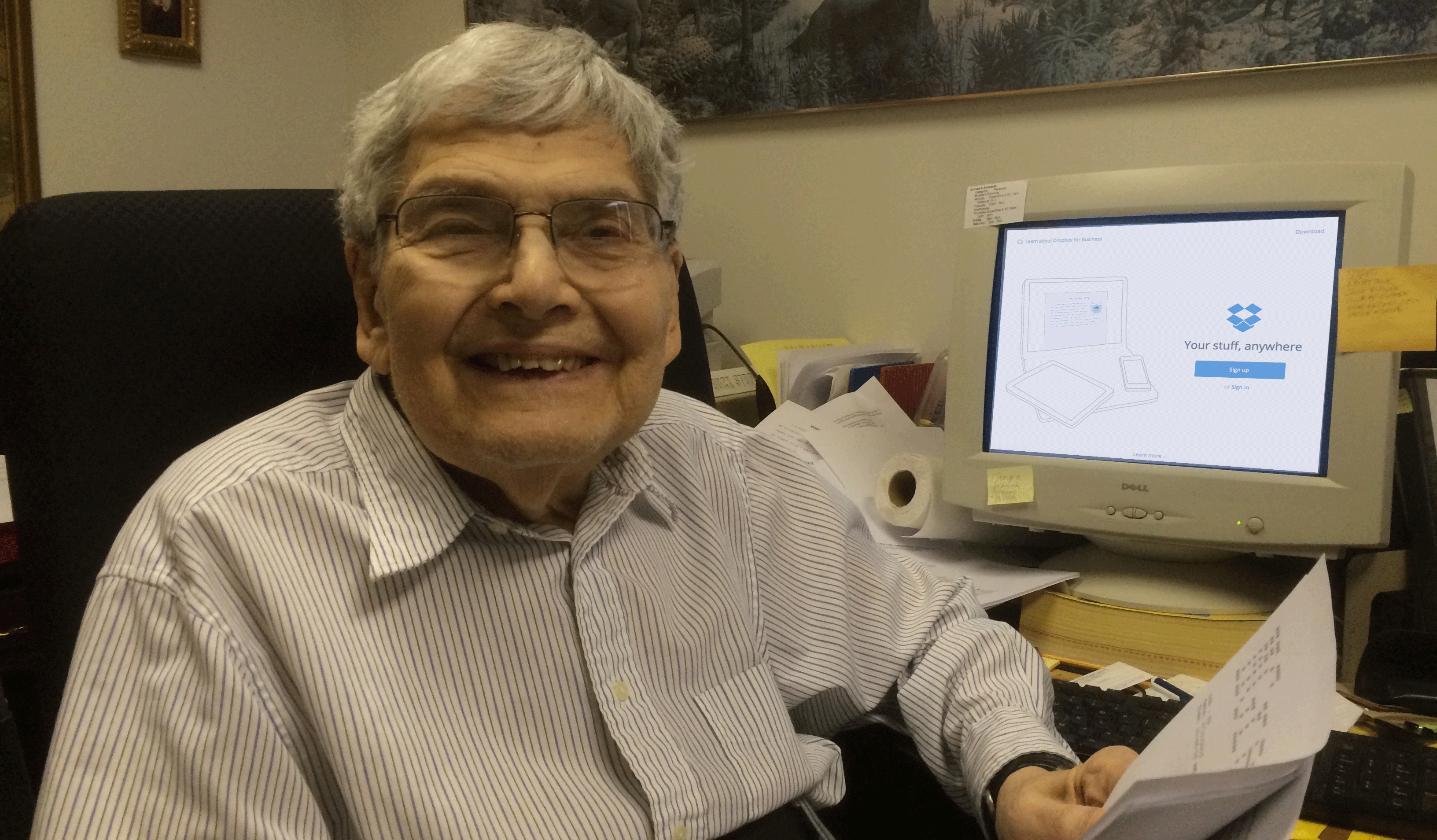

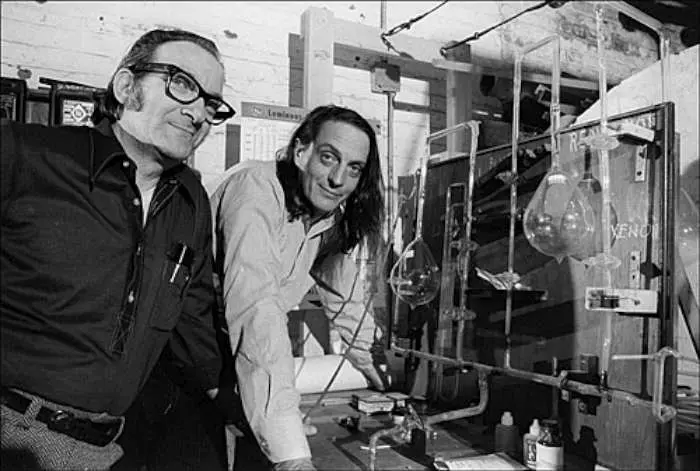

New York City-based neon fabricator and gallery Let There Be Neon has been a part of that history since its founder—filmmaker and light artist Rudi Stern—opened shop in 1972. Come to think of it, they’ve probably made a neon sign you’ve seen before. Over the years, they’ve restored iconic neon signs from yesteryear, making old luncheonettes, bars, hotels, and theaters shine again for a new generation of movers and shakers. With clients ranging from commercial giants like Bloomingdales and Shake Shack to individual consumers, there’s a good chance you’ve seen their work.

A three-month-long-2020-pandemic-induced lull notwithstanding, Let There Be Neon has been doing brisk work for 50 years. The business’ longevity bucks a common misperception about neon: that its best days are behind it.

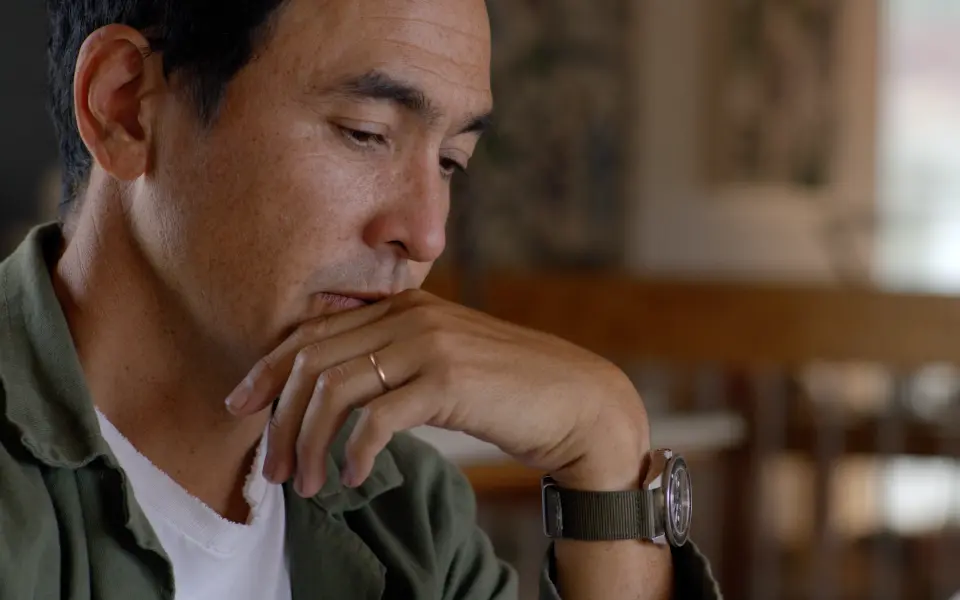

“Neon has been given an obituary every 10 or 15 years or so,” says Jeff Friedman, Let There Be Neon’s owner and operator since 1990. “And at this point, it’s kind of funny. If I had a nickel for every time somebody say, ‘Oh, I hear neon’s coming back!’ But it never went anywhere!”

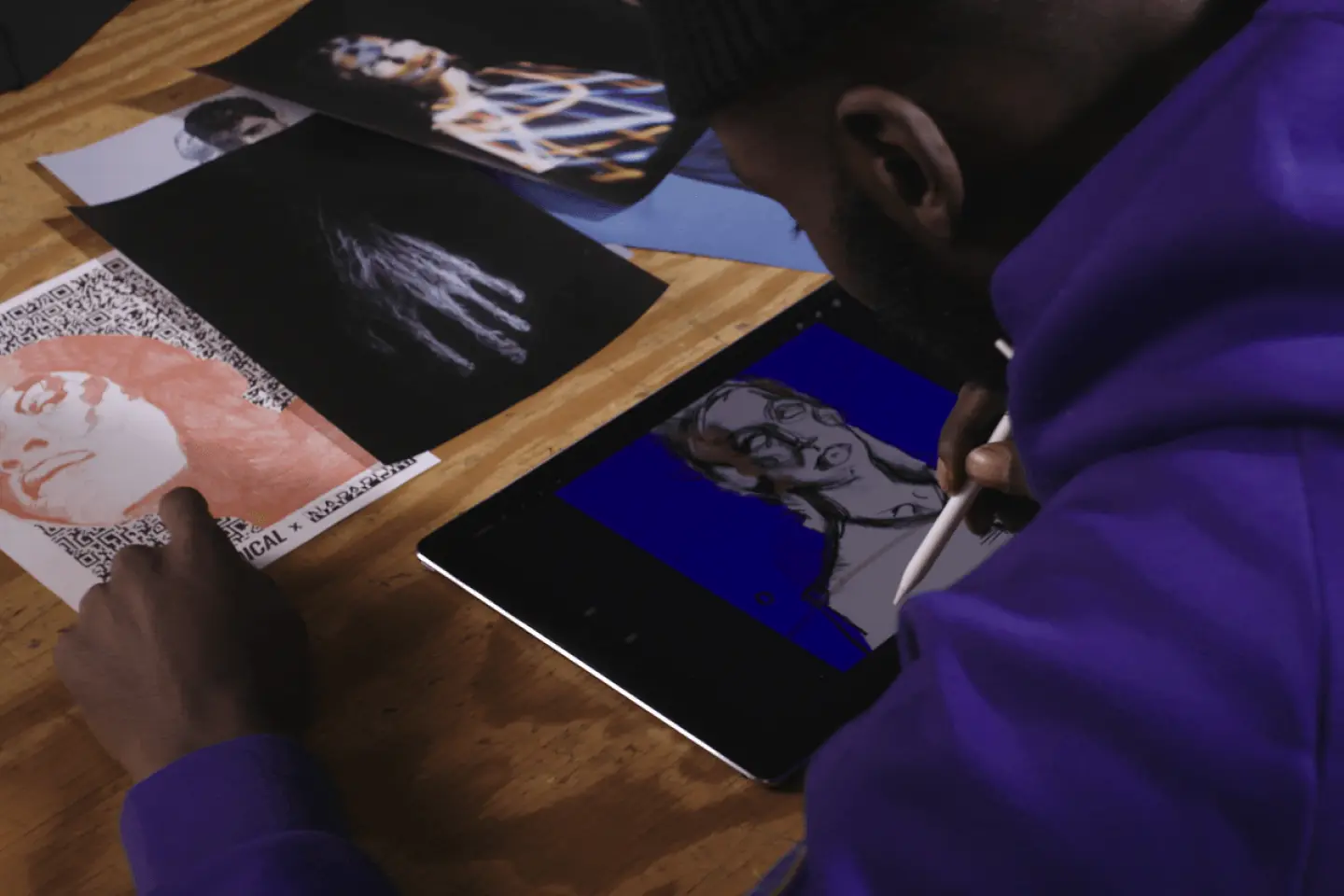

In fact, neon has expanded beyond pure advertising to become a celebrated and respected medium in the art world. And that’s in no small part thanks to Let There Be Neon. For as long as the shop has been open, it has worked with major artists interested in tapping into that unique something neon lights up in all of us.

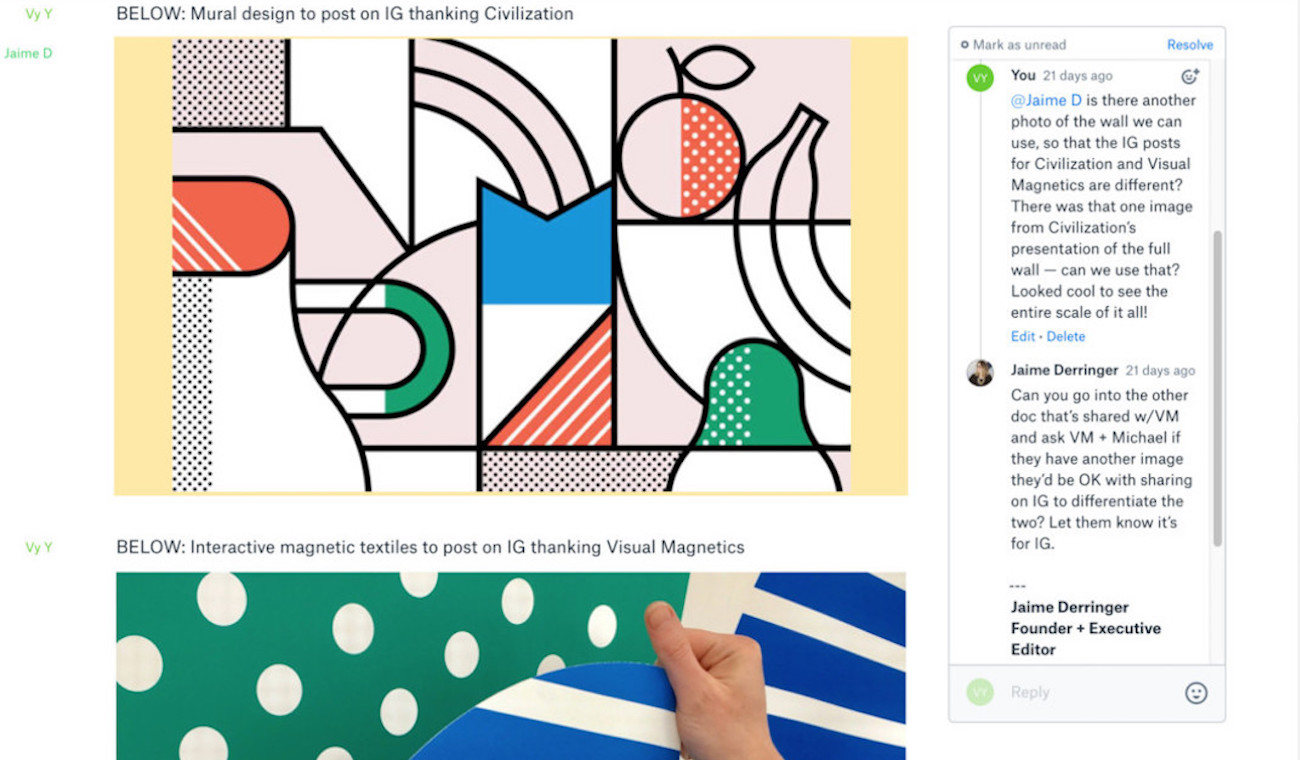

“We always work direct[ly] with the artists themselves,” Friedman explains. “They might not be able to communicate in the technical terms that we use for neon, but once you work with somebody a couple of times, you understand what their intent is."

Contemporary artists like Keith Haring, Robert Rauschenberg, John Lennon, and Yoko Ono all partnered with Let There Be Neon in its early days, according to Artsy. Those early collaborations were fruitful and genre-shifting, but also confined by geography. Given the nature of how neon signs are made, the team could only work with artists and gallery spaces a subway ride away. That began to change slightly with the advent of zip drives, but even then the process was drawn out as one party had to wait for the other to send or receive designs.

These days, Let There Be Neon is able to collaborate with artists remotely from all corners of the world by using Dropbox. Today, their artist clients include British artists Tracey Emin and Martin Creed, and Ragnar Kjartansson in Iceland.

An age-old practice gets a major upgrade

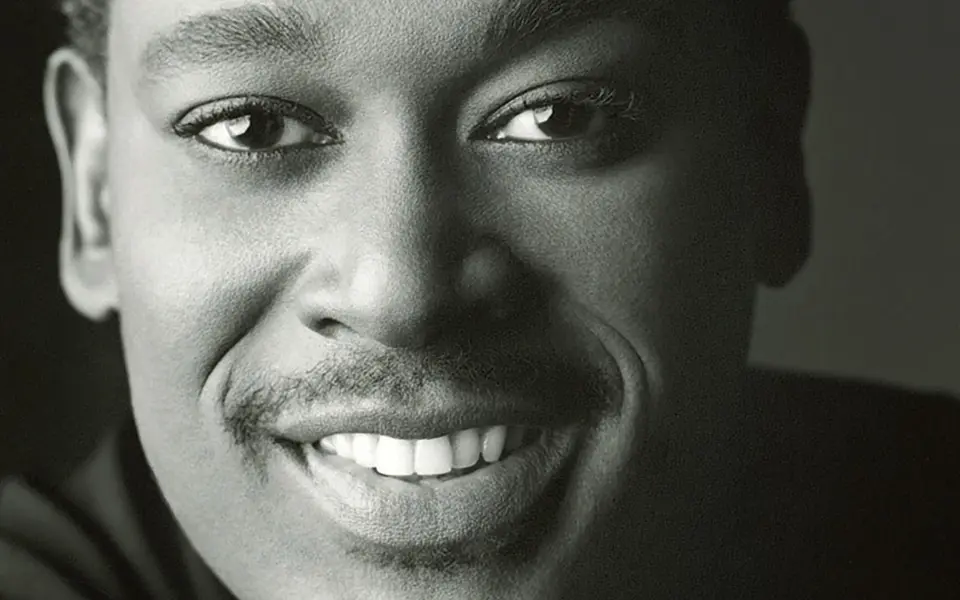

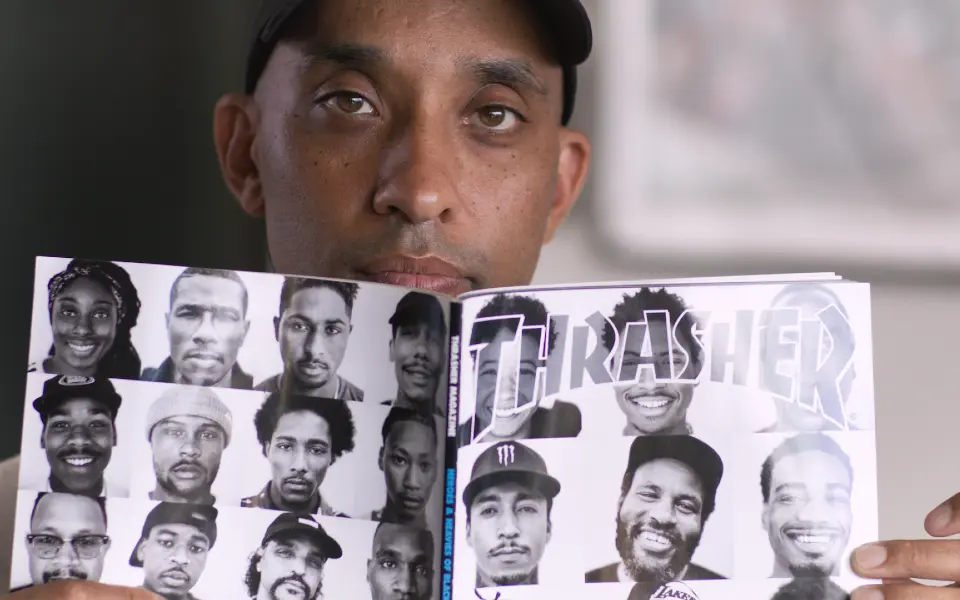

This symbiotic relationship has created a wide range of work, some cheeky (like the spiral of blue neon poop next to statues of cloud-painted, derpy-looking dogs on a daisy-covered grassy knoll in Christopher Myers’ Doggy Heaven) and others more profound. Take Hank Willis Thomas’ Remember Me (2022). The 95-foot-long phrase—and the font it’s written in—was taken directly from a photo-turned-postcard of a young Buffalo Soldier. The Black servicemen who served in the late 1800s have largely been made into a footnote in American history, if they appear at all. Using neon at that scale makes that erasure impossible to ignore.

“People, when they view [neon], it’s unexpected. [That] feeling of surprise then brings with it a feeling of elation,” Friedman says. “Believe me, [there are] always people who say, ‘What the heck is that? That’s horrible! What did they do?’ But in a way, that’s a beautiful thing. That’s what art is, isn’t it? To challenge the senses, be it positive or negative.”

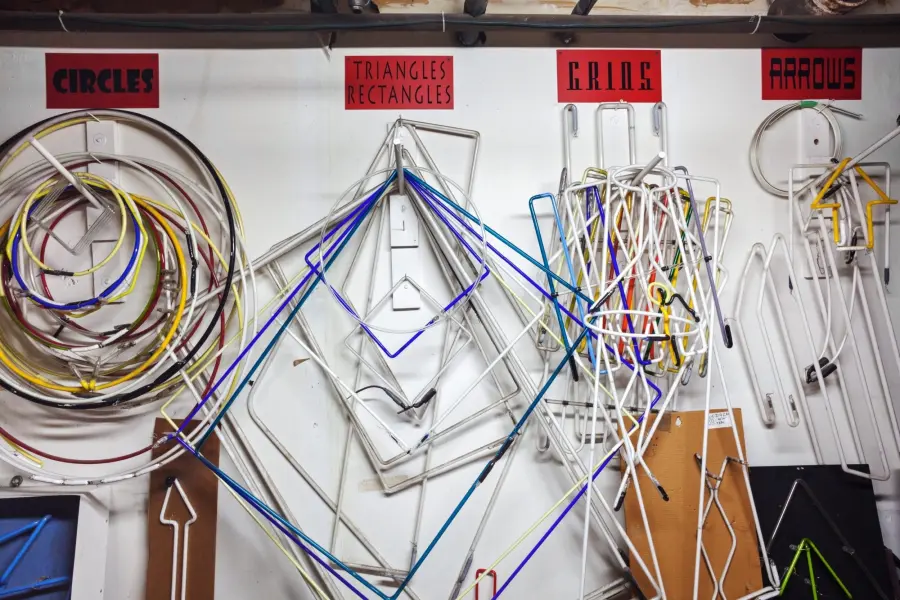

Most of the work that goes into making these pieces remains unchanged: It’s still equal parts art and science, as it was in Georges Claude’s days. Neon sign fabrication is fascinating to watch, and complicated to explain, but here’s the gist. A sign’s design is first rendered on a life-size sheet. A glass bender then takes colored hollow glass tubes and subjects sections of them to a propane flame that can reach 1,200+° F. This makes the tubing malleable enough to bend, with the bender checking their progress against the drawing.

The tubing’s final shape comes together through a mixture of fire and air (the bender blows into the tubing to keep it from falling flat), before electrodes are fused and mercury and argon and neon gases are injected into the tube, and then finally sealed off. “Adjusting the gas mixture and tinting or coating the tubes allowed for more than 40 different color combinations,” according to Science History. As Friedman has put it, it’s “like mixing watercolors with light.”

What has changed in the last century is the first part: making the design. Now, instead of benders following a freehand drawing made on sheets of asbestos (sidenote: yikes), designs are printed out on nontoxic paper from graphic files.

These files are huge and plentiful, making Dropbox a no brainer for Let There Be Neon. Friedman and his team and their partners work together within shared folders where they collaborate and iterate on projects.

“It became a tool for us early on,” he says. “We need the speed [that Dropbox offers]. Drawings have to be revised, details need to be added… We’re able to share any revisions via the service and get them to the other party almost instantaneously.”

Using Dropbox to put out neon fires

Having that information-sharing infrastructure in place has been vital in Let There Be Neon’s collaborations with artists on public art installations.

“During the installation, you know your plan as much as you can,” Friedman says. “You do as many site visits and measures as possible.”

That said, “neon is so unusual—it’s such a niche—so of course there’s challenges. We put out fires all the time.”

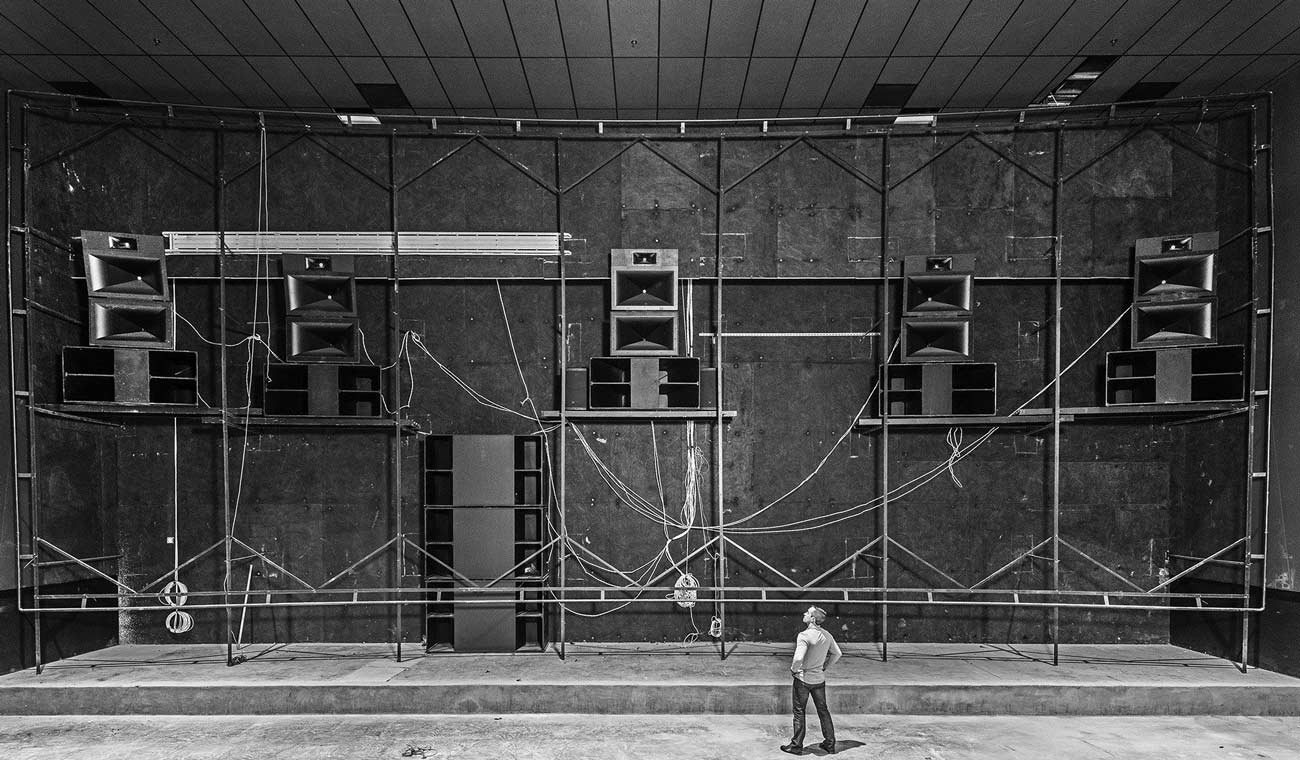

An example of that is from Let There Be Neon’s work on Ivan Navarro’s The Ladder (Sun or Moon) (2020). The 95’ tall white-neon-and-steel sculpture, which acts as a nonfunctioning fire escape, took three years to make. To hear Friedman tell it, it’s easy to imagine the cross-country project taking even longer without the “speed and clarity” Dropbox provided.

The Brooklyn-based artist’s architect sent Let There Be Neon CAD drawings, “and then we had to convert those—because we don’t work in CAD—[and send them] to our local installers out in Los Angeles,” Friedman explains.

Multiple parties based in New York City, Los Angeles, and San Francisco—general contractors, steel and aluminum suppliers, municipal planning board, and a certified-in-California welder—needed access to up-to-date information throughout the build.

“All this passing of drawings and details and regulations… [Dropbox] is where everything fell into place. It sped up the downtime and questions got answered quicker.”

That was true in the design and engineering process, and even more so once installation began.

“There was a particular floor [on the building’s façade] that had a slight condition that nobody realized until we were doing the installation. The artist was like, ‘No, you can’t change the sign.’ Our job is to marry the practical with the artist’s intent so that the artist is satisfied. We had to have a fast form of communication with visuals.”

Let There Be Neon was able to work with folks on the ground to make artist-approved tweaks to the design, and upload the latest version to Dropbox so production wasn’t further delayed. In spite of all the twists and turns the project took—or maybe because of them—The Ladder has the distinction of snagging the #1 spot on Friedman’s list of beloved public art projects.

“We’re fabricators and builders,” he explains. “Seeing it designed, engineered, and built successfully, and then installed with a fairly large team—from when it was on paper to when it got onto the building—is just so gratifying.”

A bright past—and an even brighter future

Let There Be Neon recently celebrated 50 years in the biz, leading the team to look back on the work they’ve done in that time. All of their projects have been organized and transferred from 250-megabyte-sized zip drives to Dropbox “for archival purposes,” Friedman says.

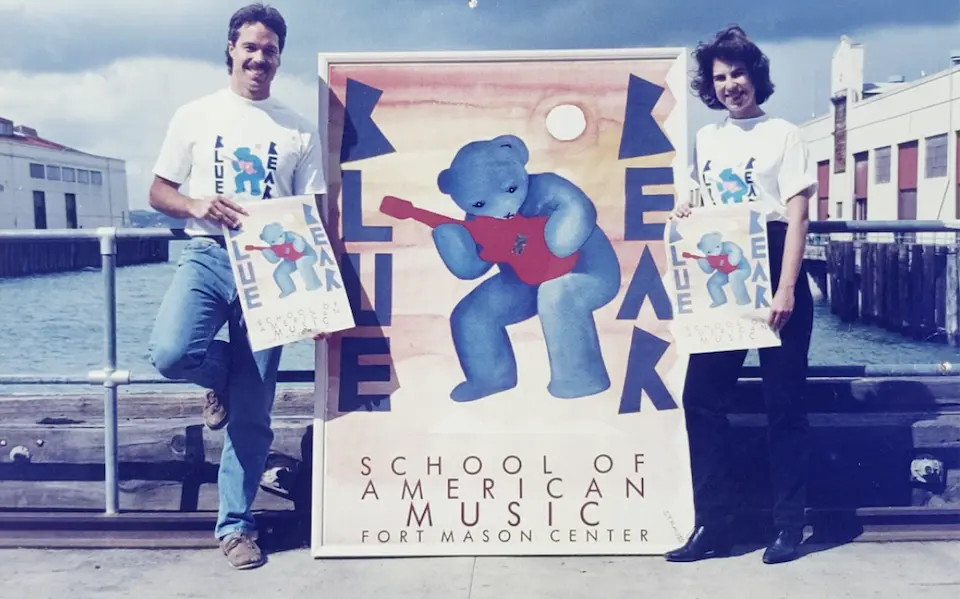

The past is very much present at the shop, from the medium they work with to the legacy of founder Rudi Stern.

“Rudi saw the beauty in the craft of neon being handmade, and wanted to do something with that,” Friedman explains, at a time when it had very much fallen out of style due to America’s near-crippling bout with stagflation in the ’70s. With businesses and consumers struggling to make ends meet, neon sign repair fell low on proprietors’ punch lists. (The rise of a cheaper alternative—signs made with plastic and fluorescent light—didn’t help either.) With many neon signs left flickering or dead, the medium developed a seedy and dangerous air, and an association with big cities’ worsening moral and economic decline.

Though the initial concept of Let There Be Neon was to showcase and sell vintage neon as “artifacts,” Friedman says, Stern wanted to create and sell signs, too, and make neon more accessible to the public.

Many of Let There Be Neon’s first projects evoked the same wonder and excitement people felt when they first saw Georges Claud’s neon lamp at the Paris Motor Show more than a century ago. There was the neon-lit dance club called Infinity Disco. And at Studio 54, Friedman told Artsy, they made “flashing, spinning neon panels [that] descended from the ceiling” to rival any disco ball.

“’I have plans for neon pavements, neon highways, neon tunnels; neon on bridges, under water, outlining trees in parks,” Mr. Stern told Omni magazine in 1981,’” The New York Times reported in his 2006 obituary.

Rudi Stern imagined a bright future with Let There Be Neon at the helm; Friedman and Co. have taken the torch. And just like neon, the shop shows no signs of burning out.

Introducing Dash for Business

Introducing Dash for Business

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(2).webp)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/1200x628%20(5).webp)