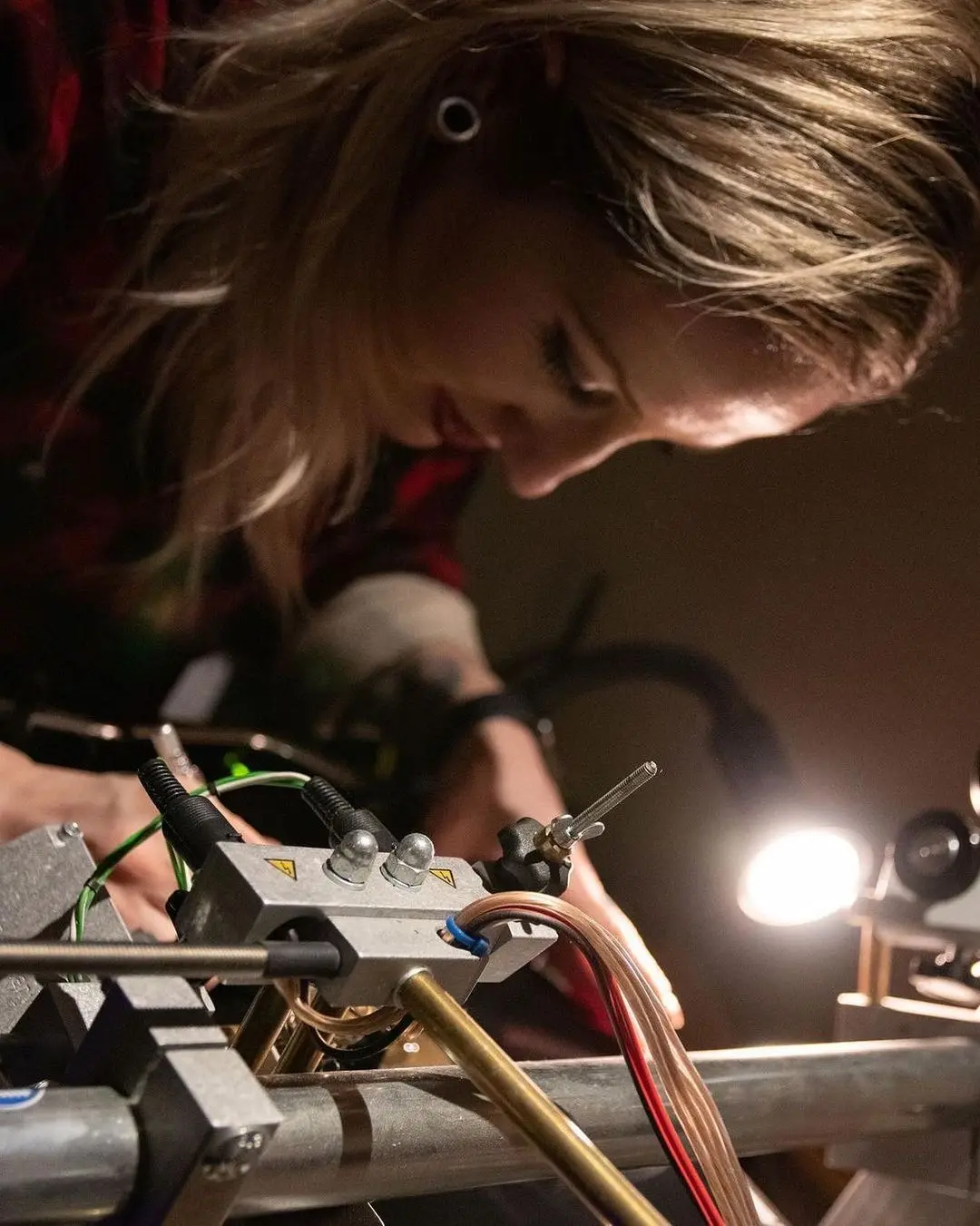

Before Robyn Raymond could learn to cut records, she would need to get a lathe—a specialized turntable for making discs, one that cuts grooves instead of playing them.

A lathe can be used to cut lacquer masters—which, in turn, are used to create metal stampers for record pressing plants—or they can be used to cut direct to vinyl, one record at a time. The technology hasn’t changed much in the past century, which is why one type of lathe in particular had caught Raymond’s eye. It wasn’t vintage equipment, like many of the lathes still in use, but a modern design, and one of the few still being made new today. The catch? In order to buy the lathe—a Vinyl Recorder T560—she would have to travel to Germany for a crash course from the inventor himself.

But Raymond, who lived in Calgary at the time, was unfazed—and, in fact, jumped at the opportunity. “I needed someone to take me by the hand and show me how to do it,” says Raymond, who had no prior experience cutting records but an eagerness to learn. “If the person that built the thing is willing to teach you how to use the thing, do that.”

This was in 2018, and after more than a decade of working in other parts of the music business, Raymond was excited to try something new. She booked a flight, learned the basics of record cutting, and then flew back home. But Raymond's enthusiasm turned to panic once her lathe arrived in a crate at her door—dismantled, with scant instructions inside. ”I put the lid back on the crate, and I sat on my porch and I cried for like 20 minutes,” she says.

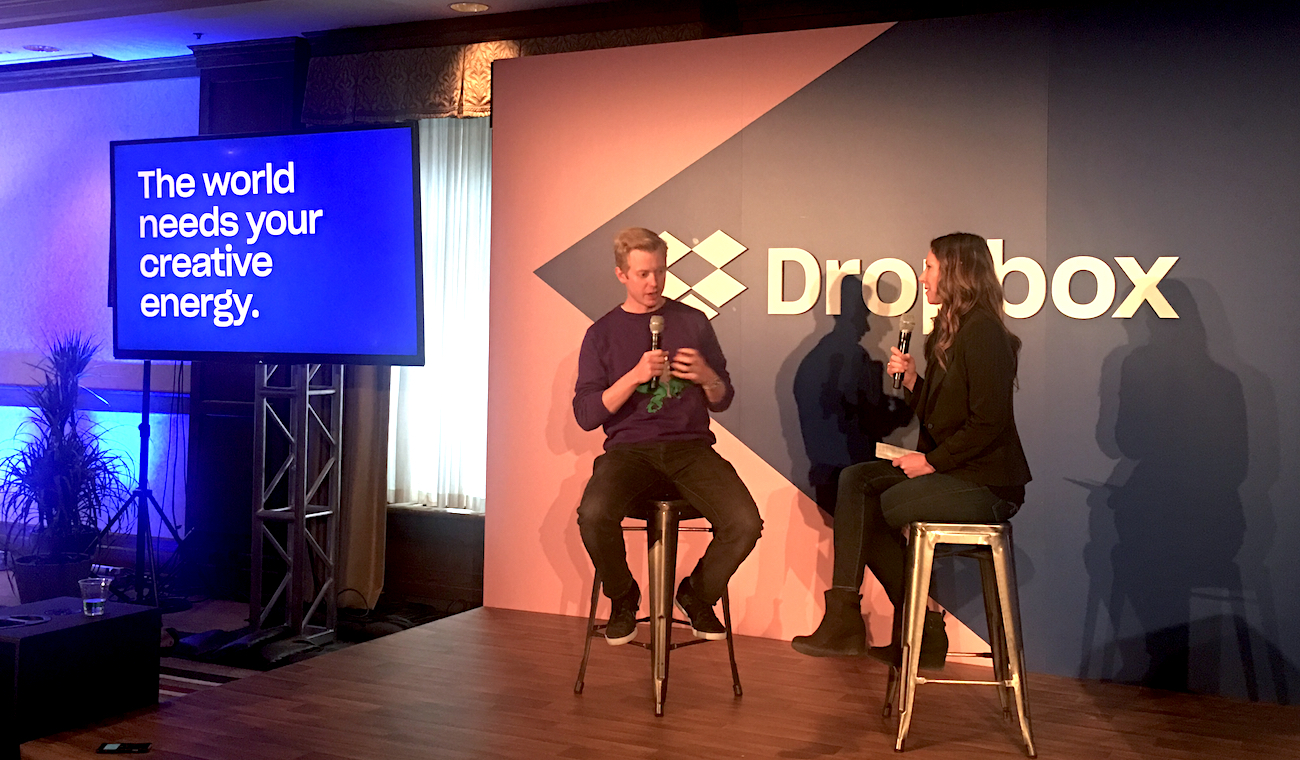

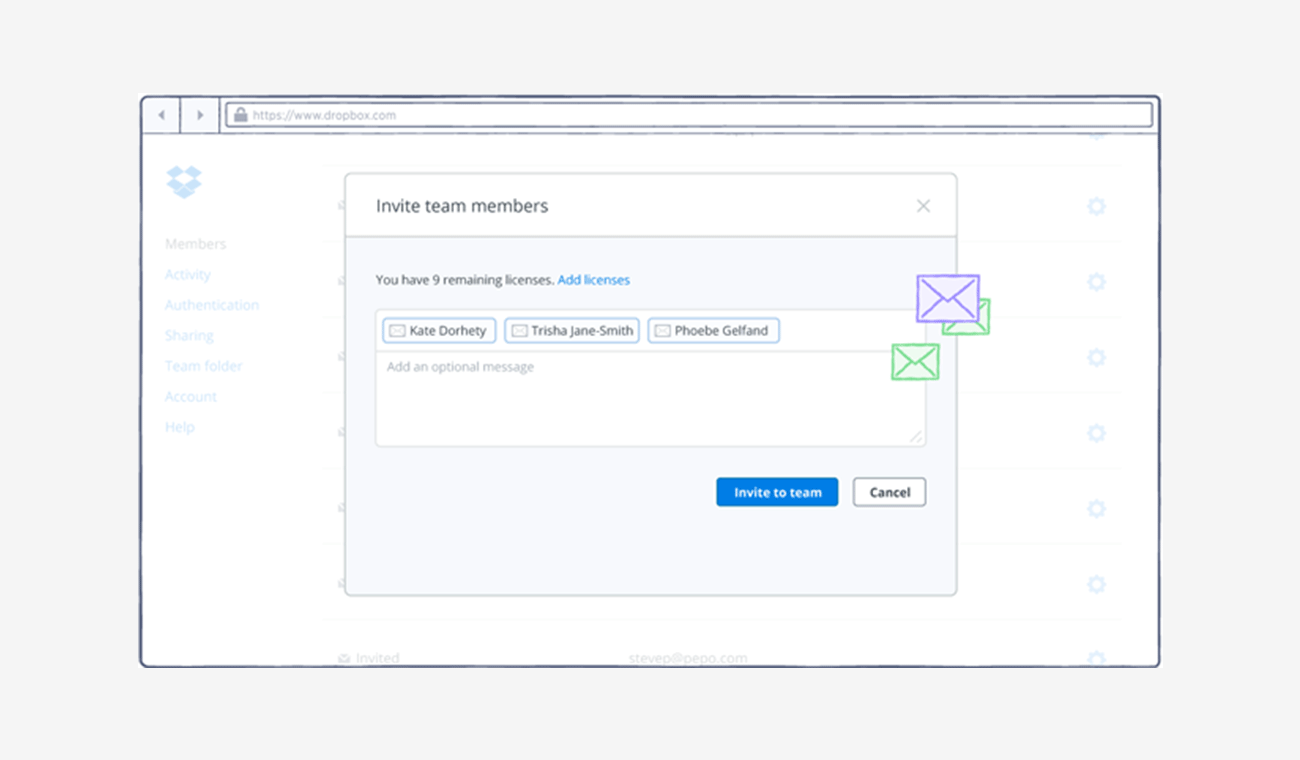

For anyone who’s struggled to find their footing in a new role, Raymond’s dread probably feels familiar. There’s the frantic search for documentation, for mentors, for others like you. It can feel overwhelming, even impossible, to know where to start. And while tools like Dropbox can make it easy to collect and organize this kind of arcane, industry-specific knowledge into one place, first you need people to share what they know. Harder still is when that knowledge only exists in peoples’ heads.

“If the person that built the thing is willing to teach you how to use the thing, do that," says Raymond

Until recently, vinyl was a dwindling format. But not only are people learning to make records again—they’re making it easier for a new generation to learn, too. Some like Raymond are cutting them by hand, while others like musician Jack White’s Third Man Records have built brand new pressing plants from scratch. Both are stewards of a century-old craft, and in every record made today is a link to that past.

For Raymond, she found encouragement in a community of other lathe cutters who were willing to show her the ropes, and then apprenticed with a pair of master cutting engineers. By 2020 she struck out on her own and started Red Spade Records, a boutique Canadian record producer—where, unlike a mass-market record pressing plant, she hand cuts records for clients herself, one vinyl at a time. She’s since cut records for acts as varied as Nancy Sinatra and the Canadian rock band Arkells—including a whopping run of 500 hand-cut holiday records for the latter. And as the only woman making lathe cut records in Canada, she’s been creating resources for a group called Women In Vinyl to make it easier for others in the music industry who want to learn, too.

“We're trying to show all of the women and non-binary identifying people that work in all of these spaces [that] this is something that anybody can do,” Raymond says.

Reviving the vintage presses

In the age of the CD and the MP3, vinyl was anachronistic, arcane. Most of the big record pressing plants shut down. People retired or passed on, and took their skills and knowledge with them. And then, against all odds, vinyl came back—and people had to learn to make records again, to bring the old machines back to life.

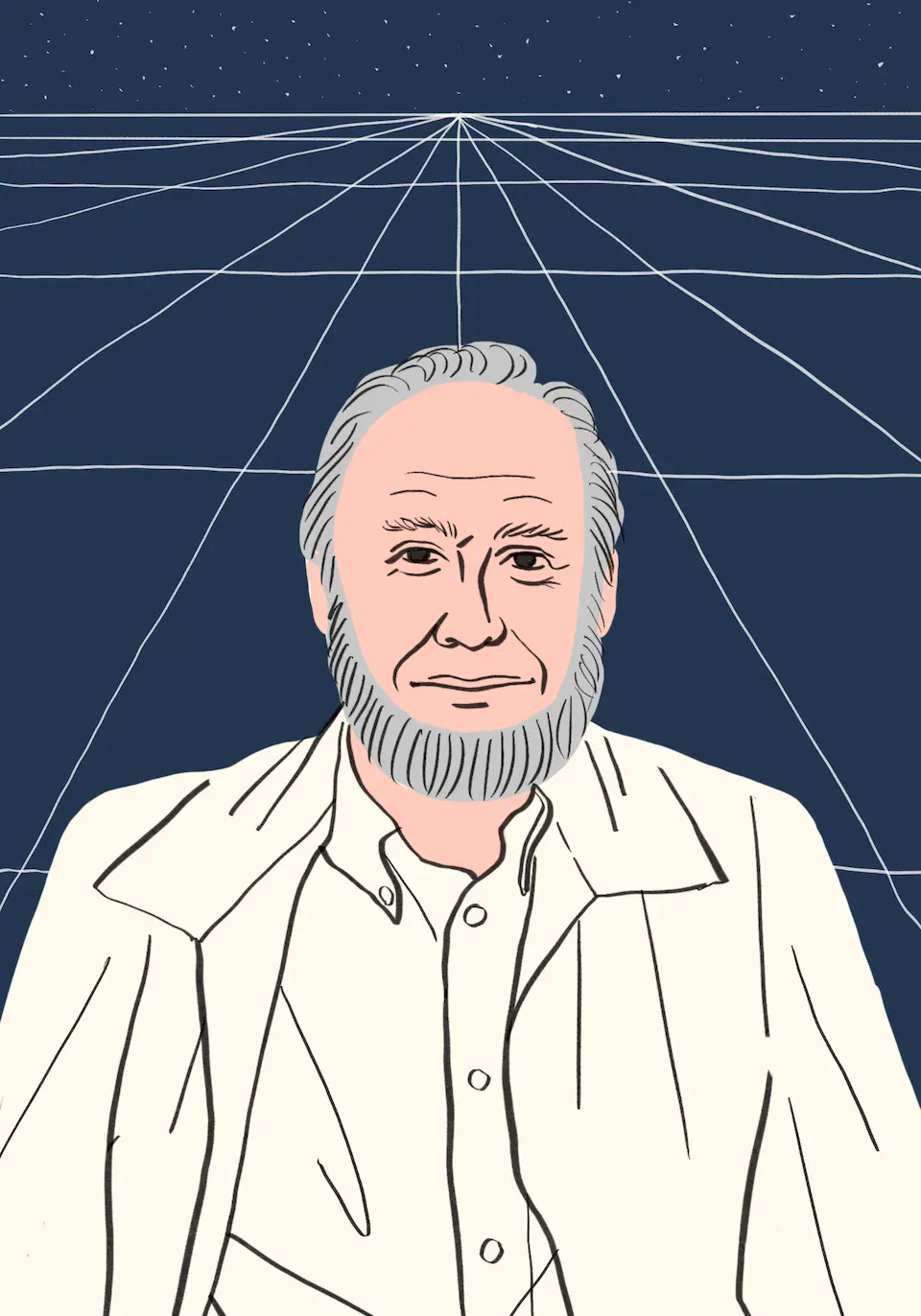

Mark Rainey knows firsthand how daunting this kind of reconstitution can be. On the manufacturing floor of Milwaukie, Oregon’s Cascade Record Pressing are eight Miller-Hamilton record presses that date from the 1970s. Four are currently in use—and keeping them running is no small feat. When a part breaks, “you're talking about something that was made 40 years ago by a company that doesn't exist anymore,” says Rainey, Cascade’s owner, co-founder, and CEO. Starting Cascade was an exercise in finding the people who still knew how things worked, and learning everything from them they could.

“We've kind of become the default experts in this particular variety of machine,” says Rainey

One of those people was Dave Miller. His family built the original Miller-Hamilton machines, and he helped Rainey and others setup a new generation of pressing plants. “He was intimately familiar with the machines,” says Rainey—and not only with how they worked, but where many of the vintage presses had ended up. When some old Miller-Hamiltons went up for sale, Miller not only picked the ones he thought Rainey should buy, but flew out to Milwaukee to consult before Rainey had them installed. “He was here like for a weekend or something, but he helped us with mapping out the basic layout of the plant,” Rainey said.

Cascade opened its doors in 2015, right on time for vinyl’s resurgence, and today business is booming. Rainey says they’re running their presses seven days a week, and there’s such a high demand for records that Cascade isn’t taking any new orders for 12” vinyl. Rainey, meanwhile, has arguably become the person he was looking for when Cascade was starting out. He’s a font of knowledge for vintage record pressing equipment—he can speak at length about how his Miller-Hamilton’s work, and his 7” SMT-3600 press' former life making legendary Jamaican reggae albums—and he’s happy to share what he knows.

“We've kind of become the default experts in this particular variety of machine,” says Rainey, who keep tabs on all the remaining Miller-Hamilton presses still in use, whether for parts or a future expansion. “So we're just going to stick with it.”

A modern manufacturing mindset

At Third Man Pressing in Detroit, making vinyl is, quite literally, a well-oiled machine. What started as a passion project by musician Jack White to manufacture his label’s own records now produces an average of 4,700 records each day for indie and major labels alike.

When Third Man Pressing opened its pressing plant in 2017, it had the unlikely opportunity to figure out how to build a modern pressing operation from scratch. “We thought we were going to be like everybody else, where we had to go find the old machines [and] tinker them back to life,” says Eddie Gillis, Third Man Pressing’s operations manager. But with the resurgence of vinyl, a handful of companies had actually started making new presses again—meaning the people who built them could actually come set them up and teach everyone how they worked.

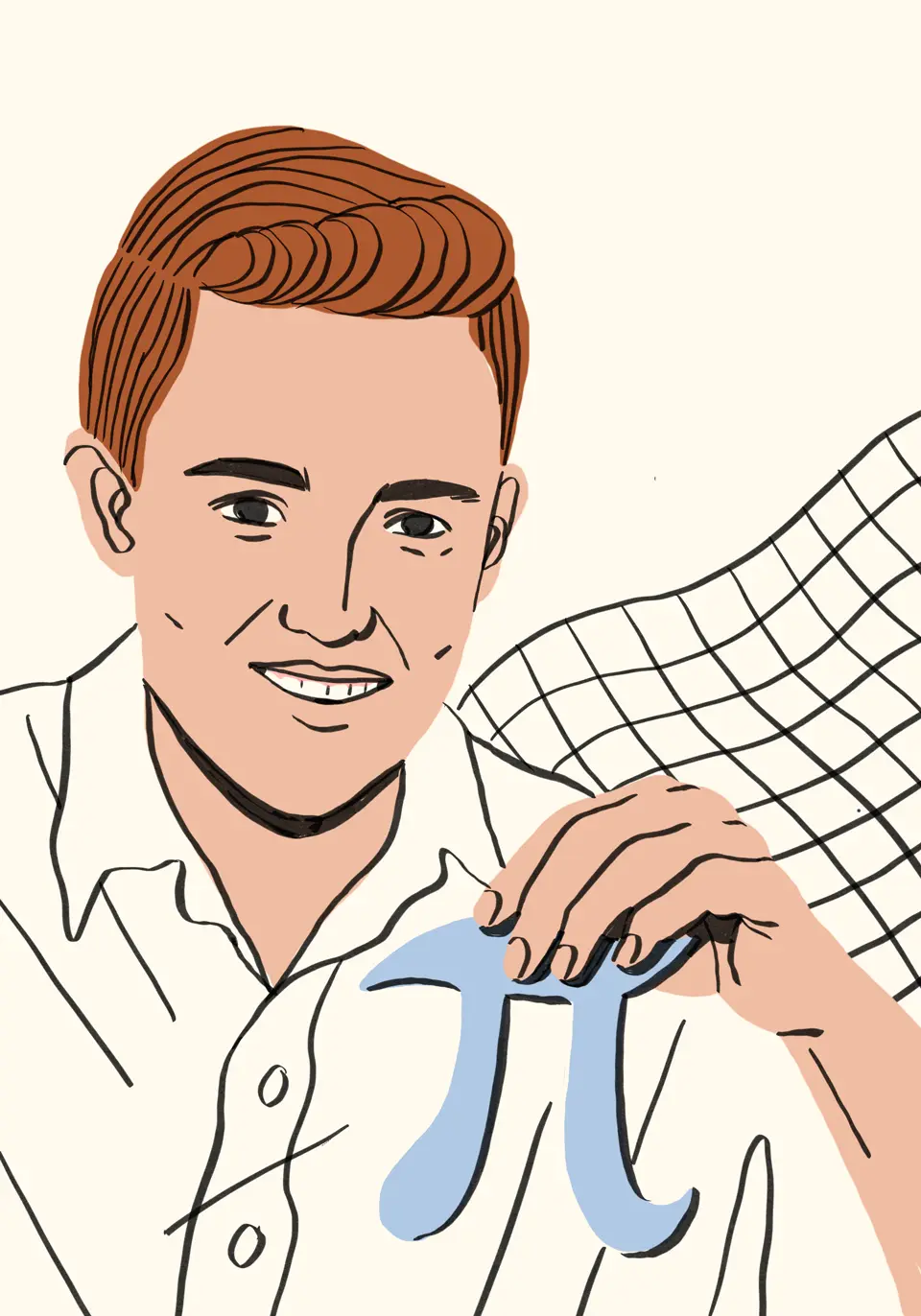

One of those companies is Toronto-based Viryl Technologies, which sells the automatic WarmTone record presses that Third Man now uses. When something goes wrong, “for the first time in decades, there’s a hotline you can call,” says James Hashmi, Viryl’s co-founder and CEO. Founded in 2015, Viryl's co-founders studied existing vintage presses—poring over old manuals and watching presses in action—before coming up with a new design of their own.

While the actual process of making a record hasn’t changed much in decades, Viryl’s new machines have been outfitted with sensors and digital controls, giving operators more fine-grained control over the pressure, steam, chilled water, hydraulics, and pneumatics that make record pressing possible. Decades after companies stopped designing new presses, Hashmi thinks they’ve built the most operator-friendly presses you can buy. Of their 30 or so customers, only a handful have ever pressed records before.

“For the first time in decades, there’s a hotline you can call" when something goes wrong, says Hashmi

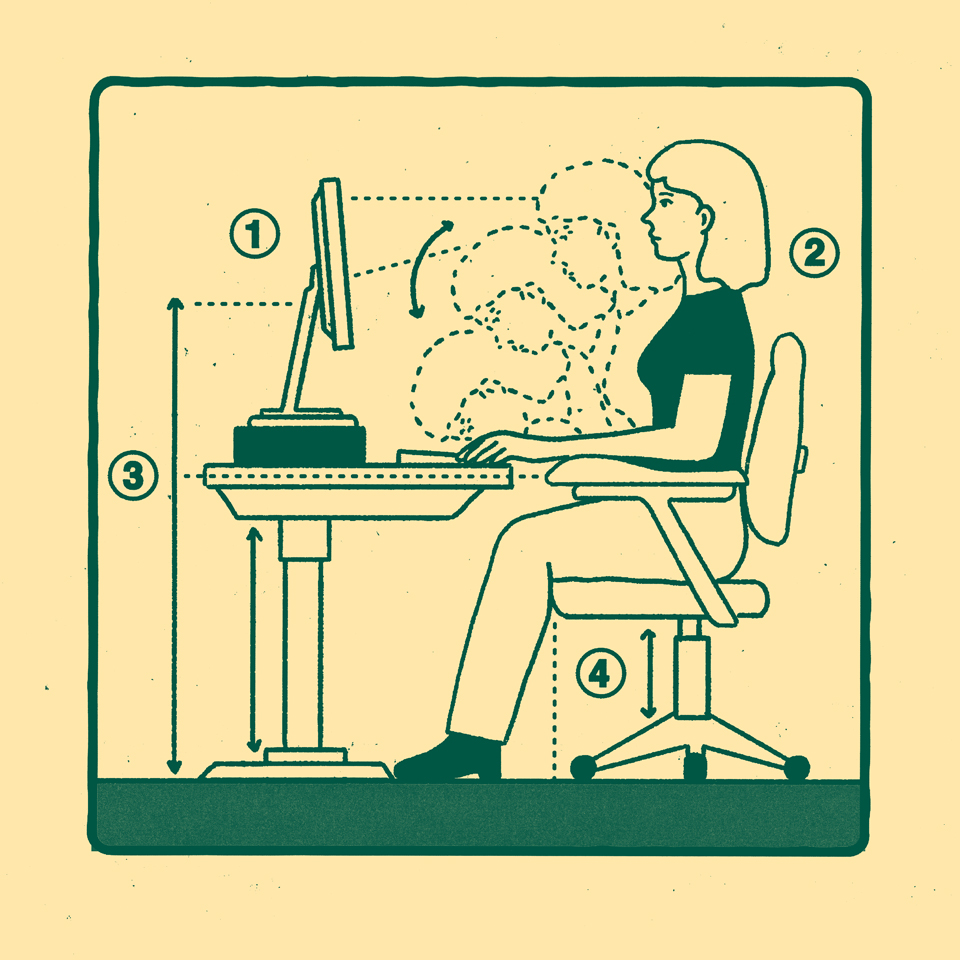

Since Broc Barnes started as plant manager for Third Man Pressing last year, he’s helped bring even more of a manufacturing mindset to the company’s work, involving more data and documentation. “I pushed our planning department into having a visual planning mechanism that would allow them to see where our jobs are versus timelines—and as things shift, what does that do for the other jobs around it,” says Barnes. They maintain living, daily documents that track how the presses are performing, for better and for worse. They also have scorecards they use to document visual defects and the sound quality of the records coming off the press. And as they hire more press operators to keep up with demand, they’re writing work instructions to help new employees learn how to operate the presses and remove any inconsistencies in how records are made.

All of these processes help press operators focus on actually making records that sound the best they can be—because that “hand work,” says Gillis, is the most important part. “People actually can walk in and know ‘I'm going to be on press number five and six today, and I'm going to be running turquoise PVC, and my labels are baked and ready to go—and I don't have to go chase anybody down,” says Gillis. “Everybody has the tools they need before they walk in the door.”

Keeping the old knowledge alive

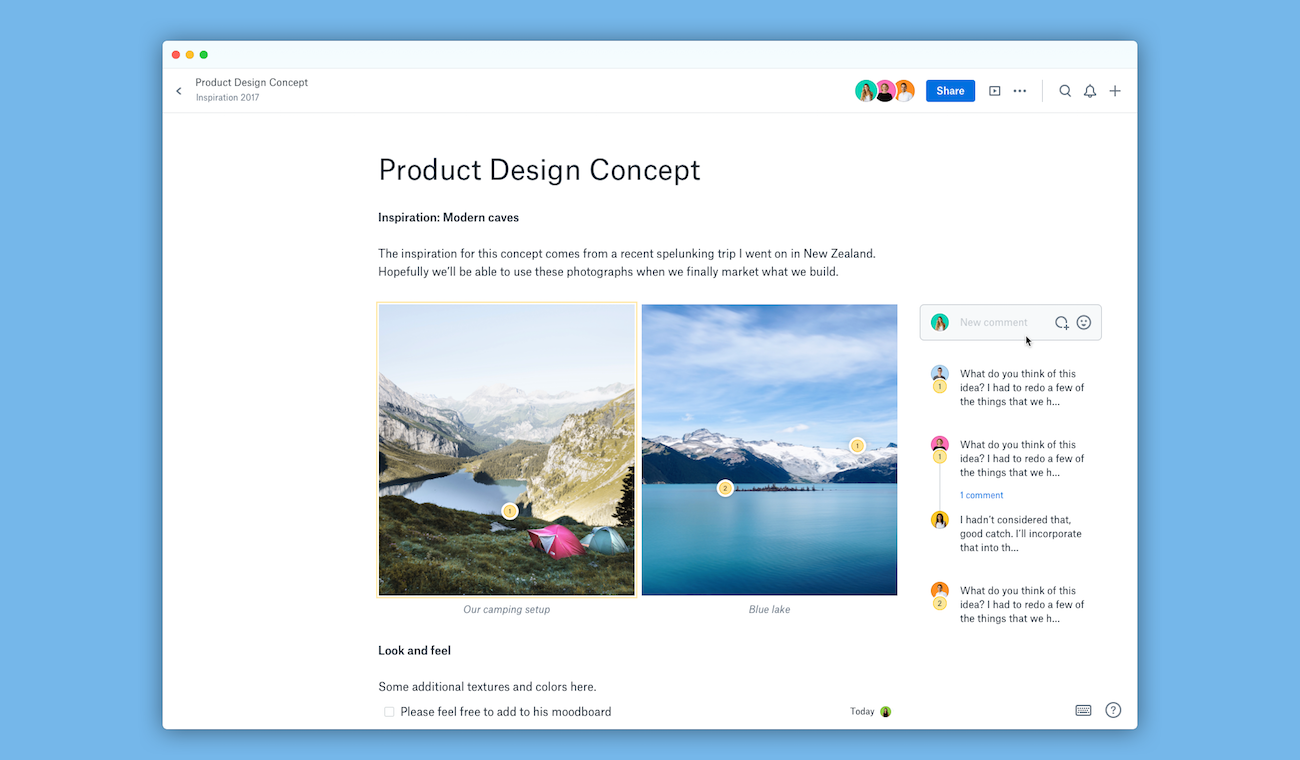

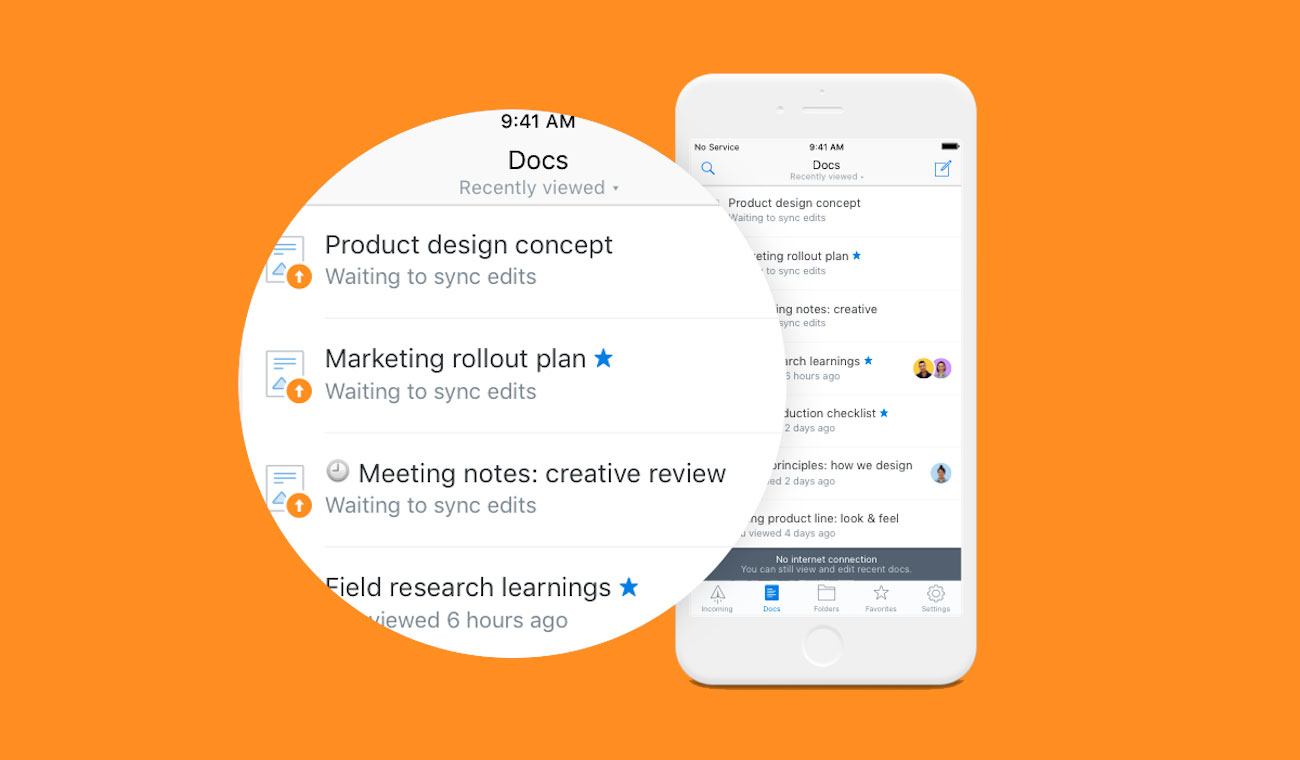

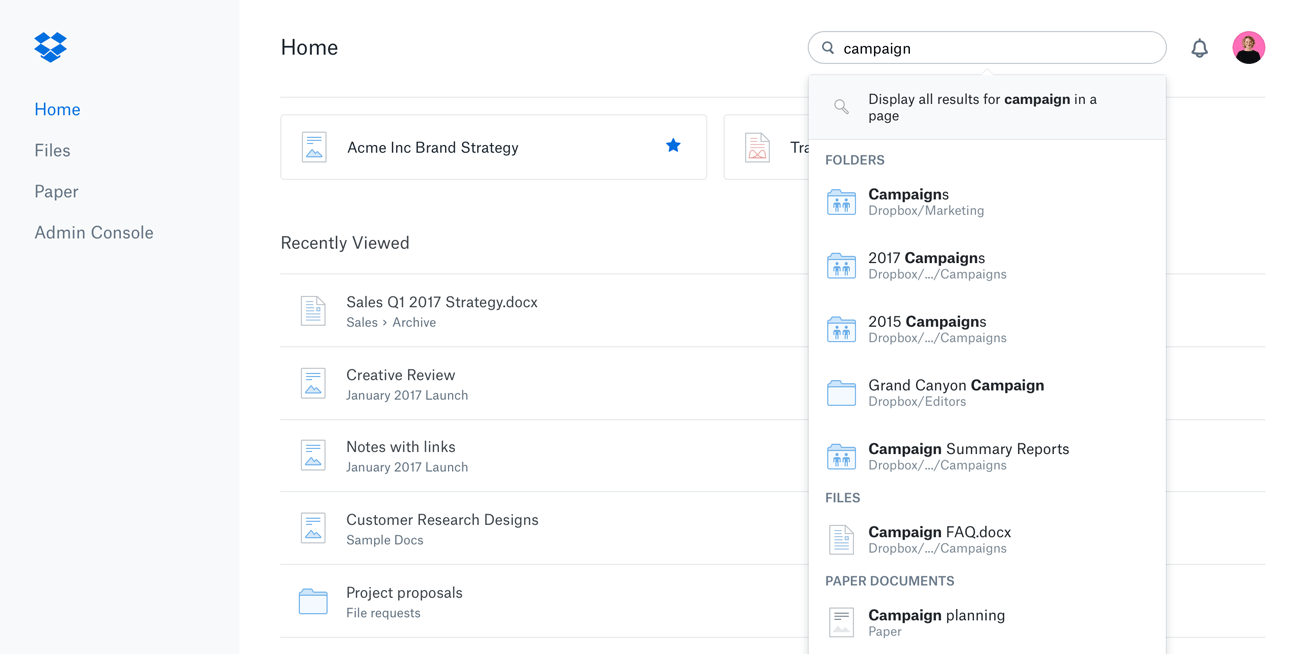

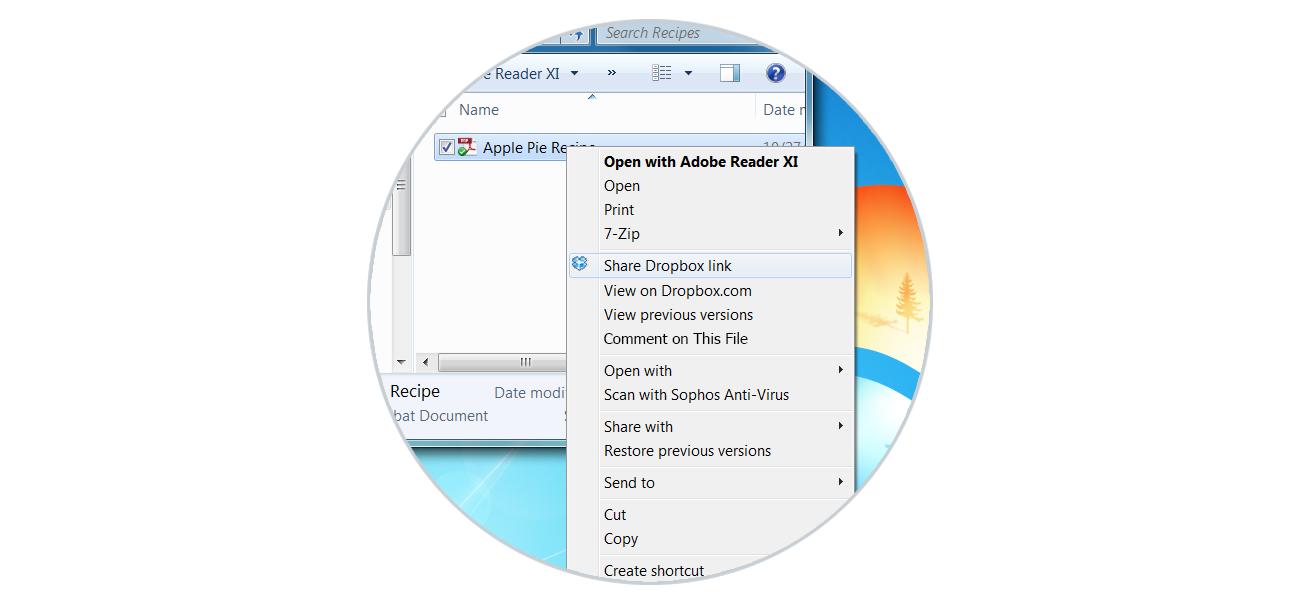

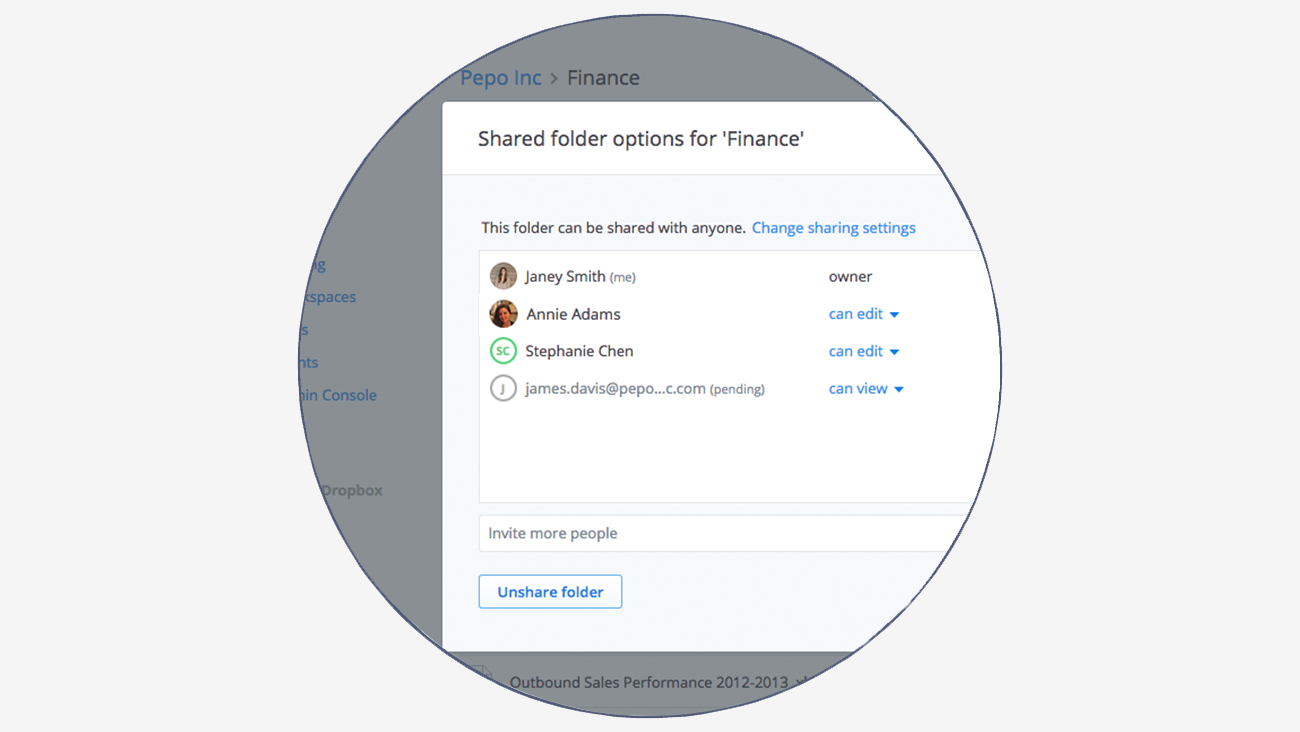

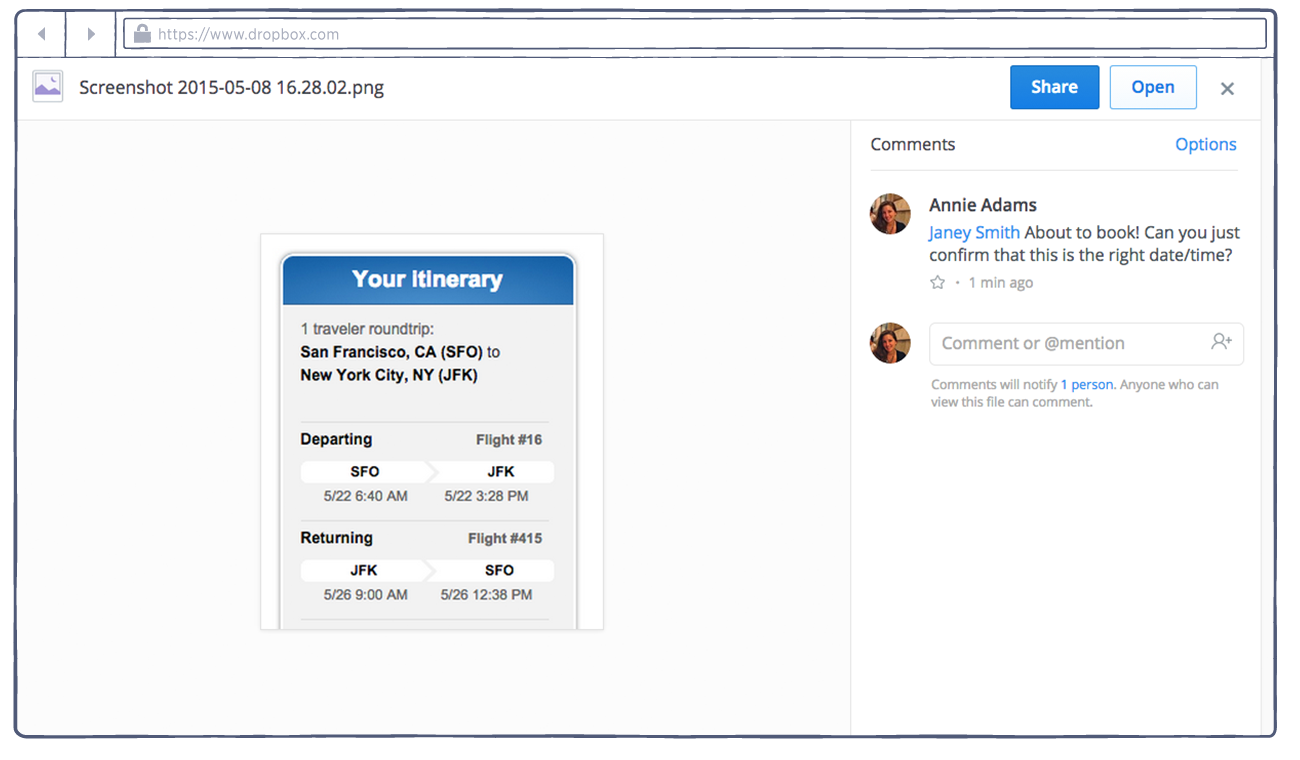

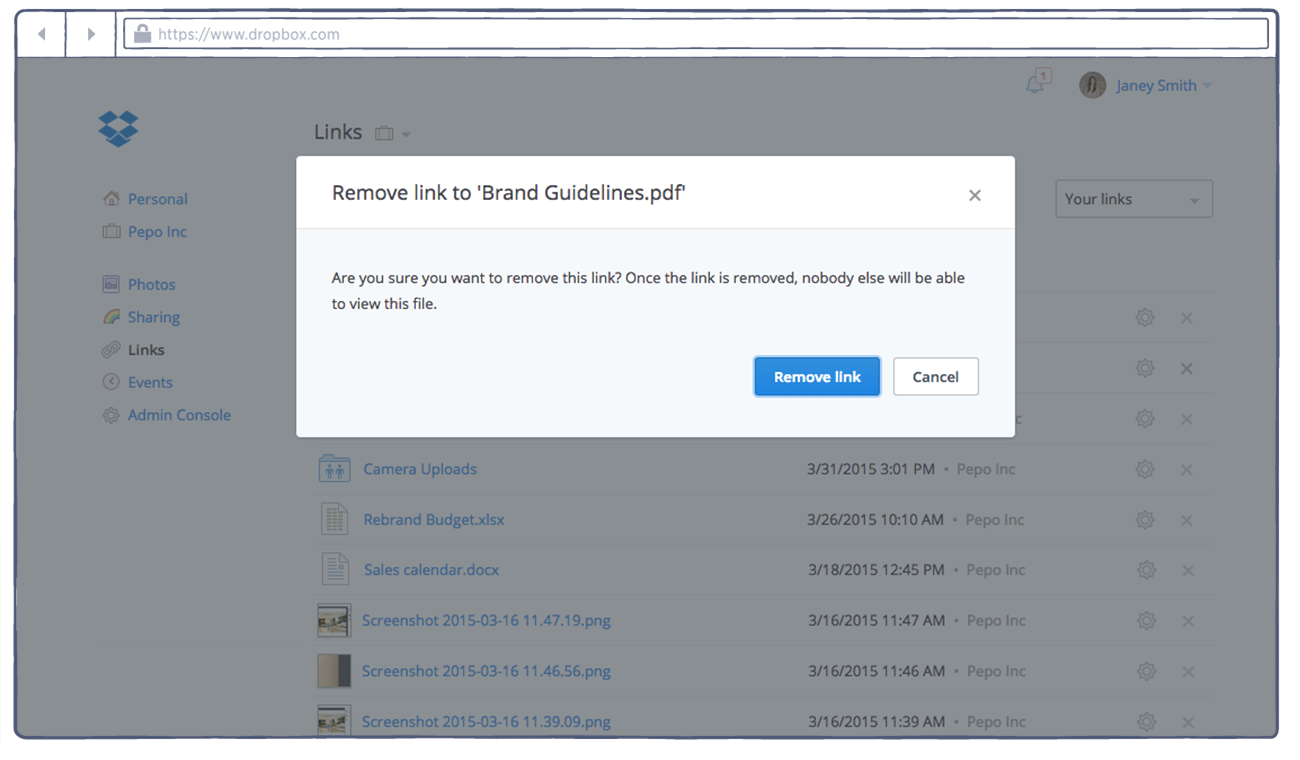

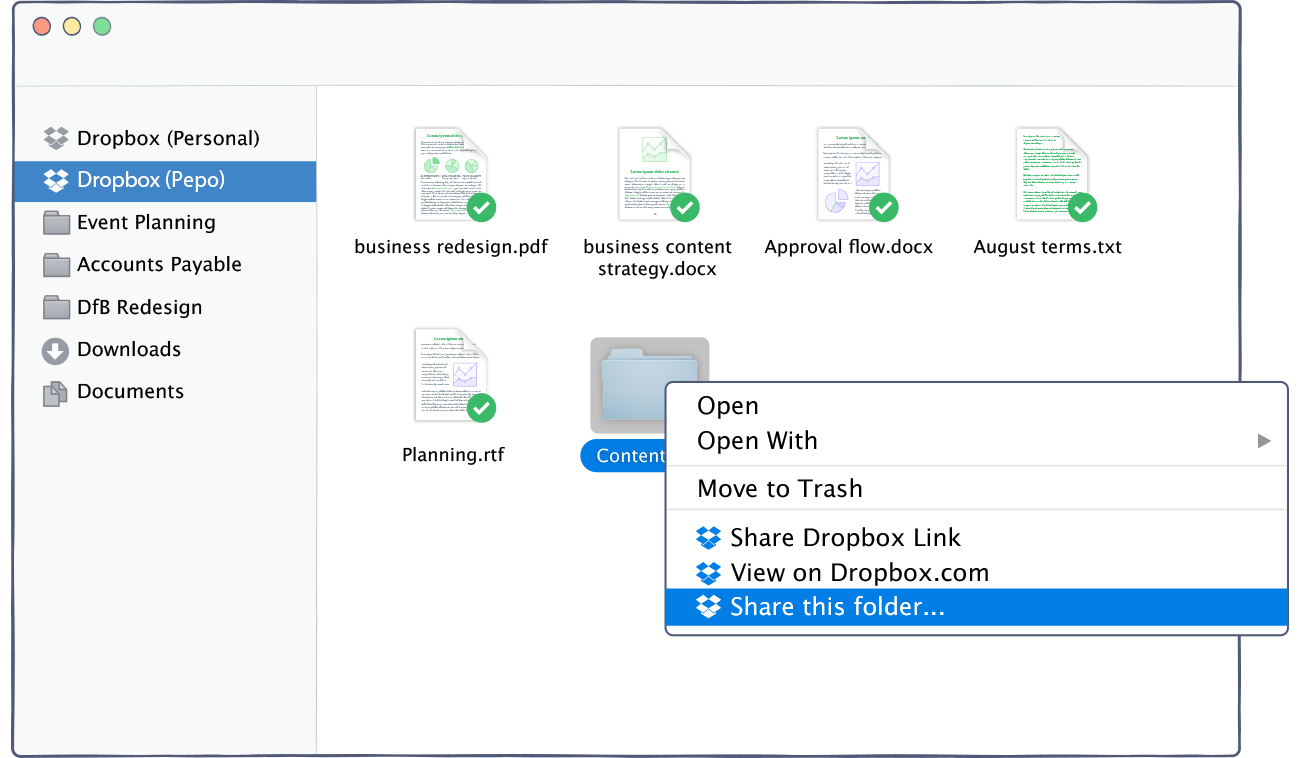

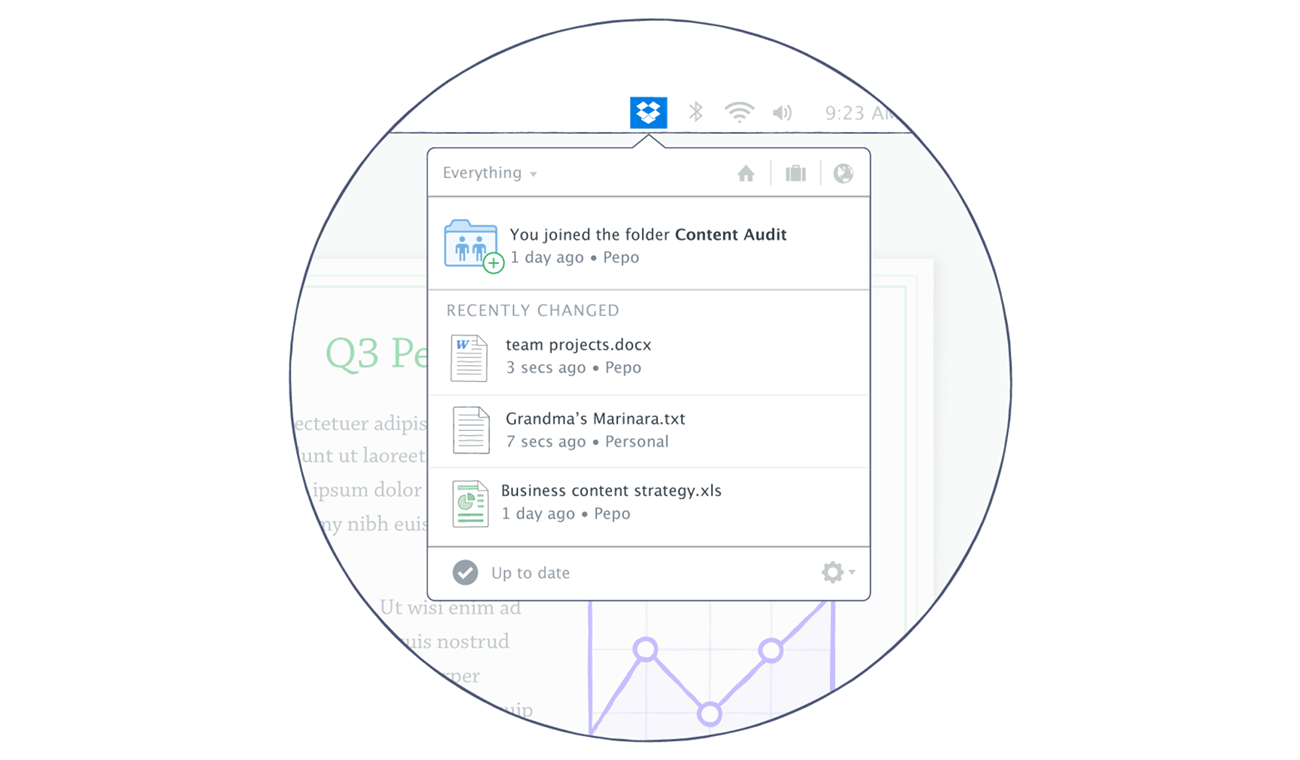

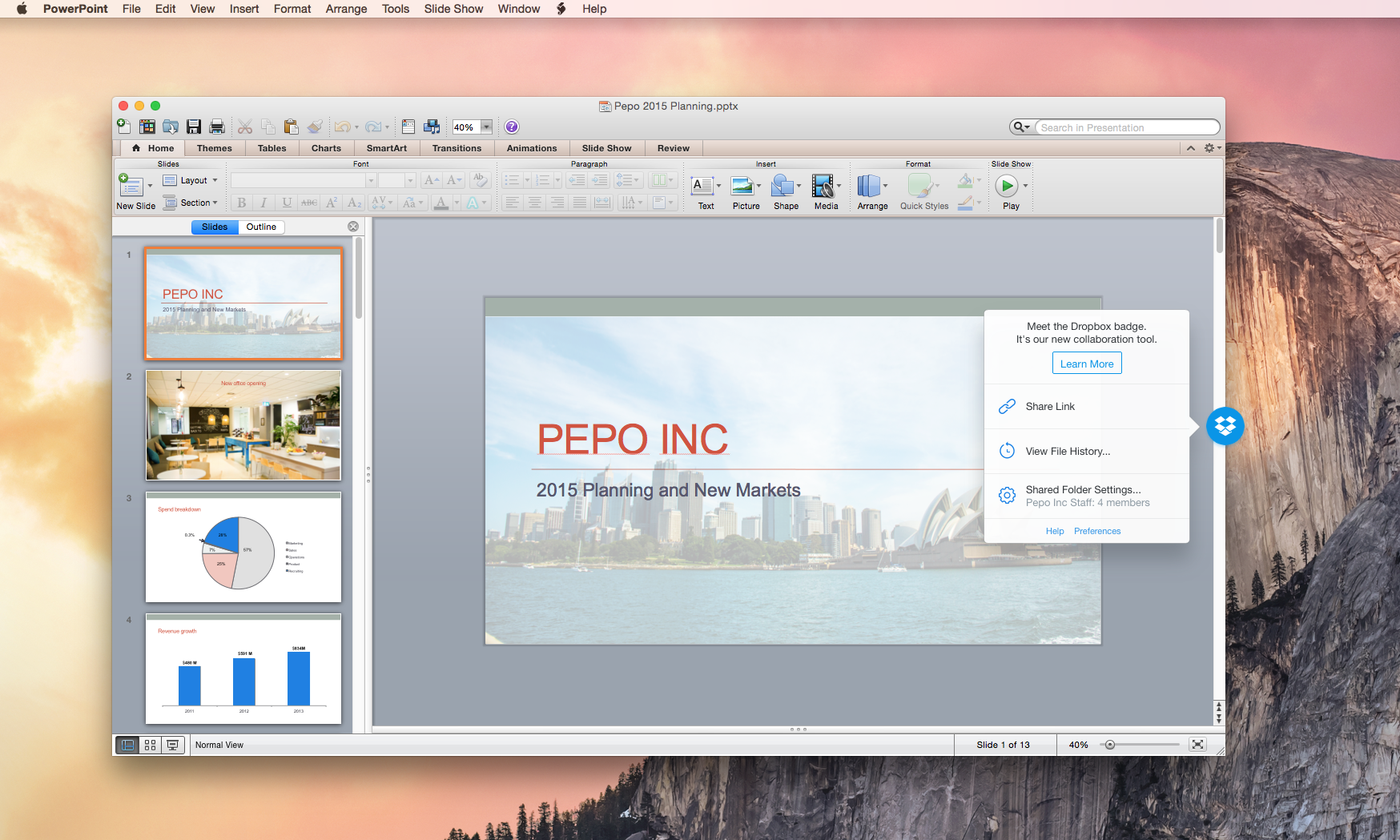

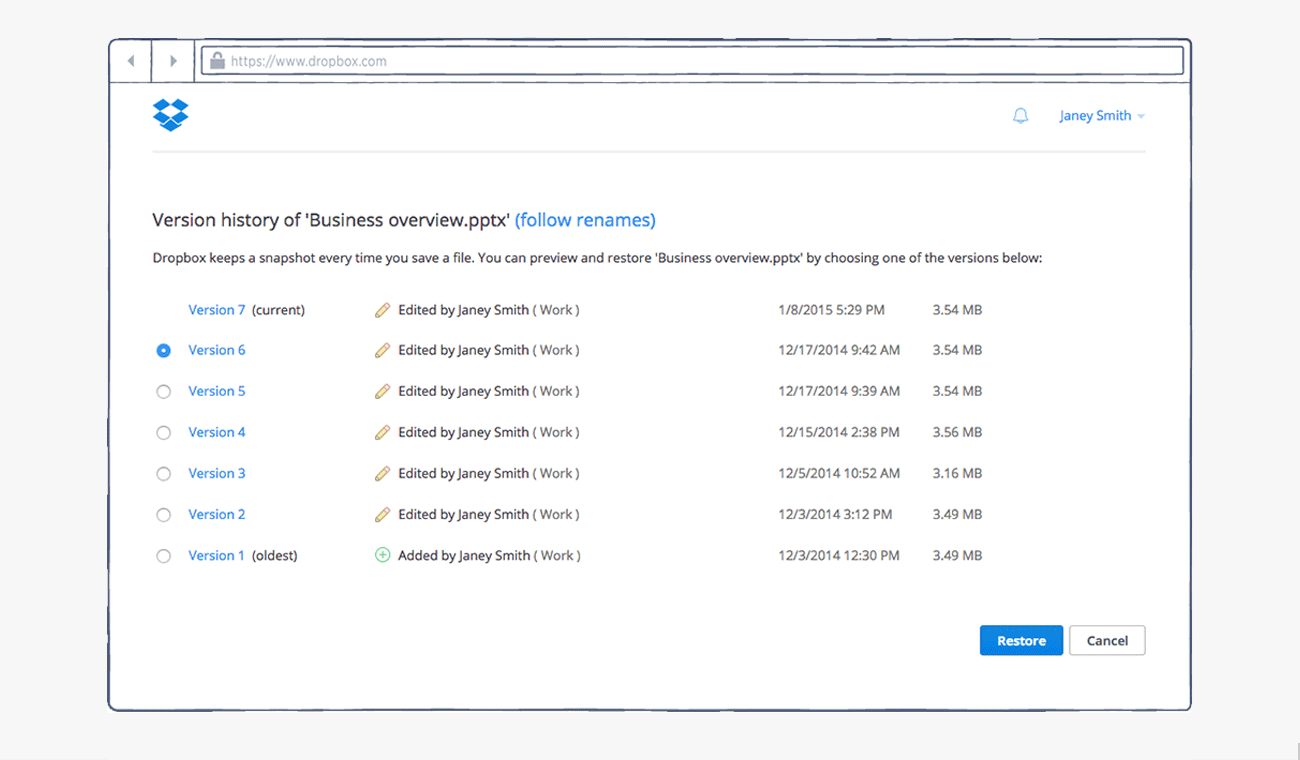

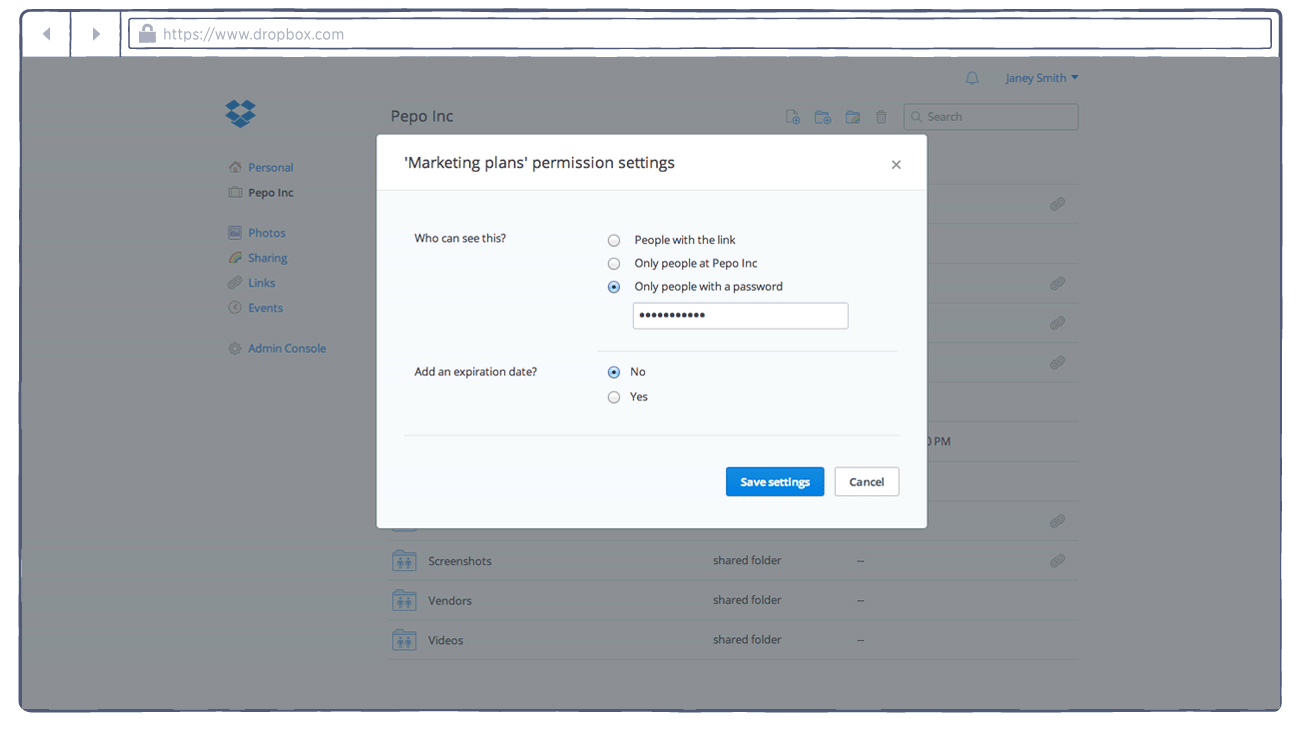

There are some parts of the record-making process that lend themselves to digital workflows better than others. Before Raymond cuts a record, she has artists submit their audio masters, labels, and jacket art to a shared Dropbox folder, so everyone is always on the same page. “[It’s] a really lovely thing to be able to have those environments to work through things and not have to worry about the newest version of a file coming,” she says. “It's just there.”

When he’s not running Cascade, Rainey also runs a label, TKO Records, and uses Dropbox to trade reference materials with album artists—who usually work remote—and to send the final high-resolution assets to the printers. And he likes that it’s a secure way to transfer songs between the studio and the mastering engineer. “Things like Dropbox, and things being more digital—it saves so much time and so much headache” says Rainey. “I can't endorse it enough.”

But in other parts of the business, there‘s still a lot of information that lives solely in peoples’ heads. Early in Raymond’s record-cutting career, she quickly discovered how little documentation existed—and that what did exist was often highly technical, hard to find, and half a century old. It was niche, bespoke knowledge, known mainly to the people who had been making records for decades, and never widely shared. And when those people retire or pass on, what then?

“We all kind of have a direct conduit to one of those people,” says Raymond. “It's like an oral history tradition that gets passed on"

“It is a concern because a lot of that information has not been disseminated evenly,” says Rainey. He’s fortunate that Cascade has been able to develop relationships with the shrinking pool of people who have been pressing records for most of their lives, and are still around to share what they know. “We try to spend as much time with these folks as we can,” says Mark. “And it's always a case of whenever you're around [them], there's no way you're not learning something.”

In any job, finding those people is key. Raymond talks about getting to meet iconic audio engineers like Bernie Grundman, who mastered records for Prince, and George Graves, who did the same for Ella Fitzgerald and Peter Gabriel. They’re the sort of people you stop and listen to whenever you can, while you still can, she says, because that’s how you keep their knowledge alive.

“We all kind of have a direct conduit to one of those people,” says Raymond. “It's like an oral history tradition that gets passed on.”

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_wide%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(3).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/blog%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_wide%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/1080x1080%20(1).webp)

.gif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)