.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(3).webp)

How AI is upending archaeology and changing the way we understand ourselves

Published on October 09, 2024

AI is automating the most time-intensive aspects of archaeology. With this leg up, can researchers delve into the deeper questions of our past?

In the year 79, when Mt. Vesuvius erupted and buried Pompeii in a pyroclastic surge, killing thousands with more thermal energy than 100,000 atomic bombs, it also dumped twenty meters of hot mud and ash on a nearby town called Herculaneum, which was something like the Malibu of ancient Rome. In this town was a luxurious villa with a massive library of papyrus scrolls. When the volcano went off, each one of these got turned into a Kingsford charcoal briquette, carbonized by the searing heat. Pyroclastic material is an excellent preservation method, making Herculaneum, like Pompeii, a near pristine museum of ancient objects—except that when Italian papyrologists tried to crack open the scrolls, they crumbled. Using traditional archaeological methods, this was a dead end.

That is, until an ambitious computer scientist from the University of Kentucky named Brent Seales proposed something radical: Pop one of these scrolls in a CT scan—a particle accelerator the size of Madison Square Garden—and unwrap it virtually with AI.

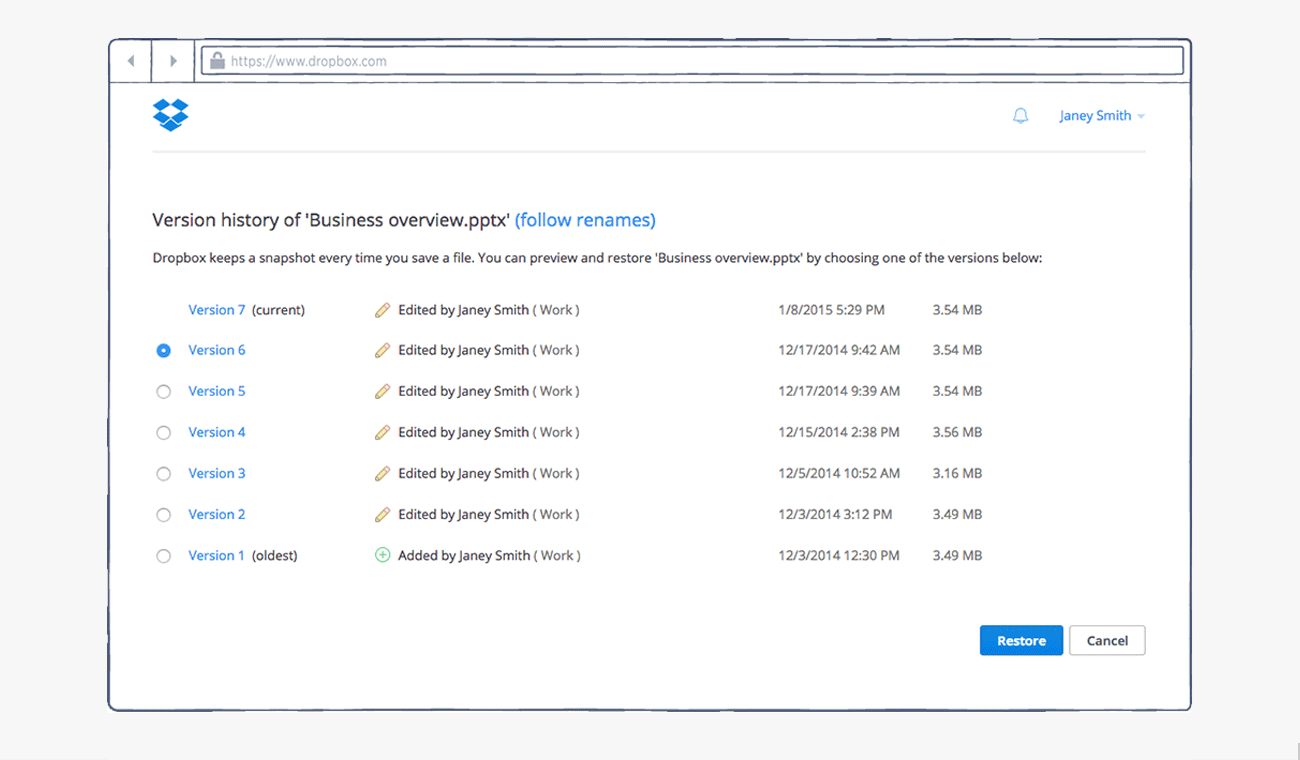

Archaeology is not a resource-rich field. And particle accelerators are expensive. So Seales created the Vesuvius Challenge: a competition between research teams to read the scans and win over $1M in prize money raised from big donors. Each step turns out to be incredibly complicated. After scanning there’s “segmentation,” which involves tracing the crumpled layers of the rolled papyrus in the 3D scan and then unrolling them. Then there’s “ink detection,” identifying which areas of the charred papyri, which look black to the naked eye, held ink and which did not using machine learning. A Discord community with over 4,000 members sprung up around this project. More than 1,000 teams jumped in. To make sure that teams weren’t hoarding intermediate discoveries from each other, they blended competition and cooperation by giving out “progress prizes” along the way.

Last year, three young students pulled it off, won the money, and revealed to the world a small portion of text—5% of just one of around 1,800 scrolls—that had been locked away for two millennia. The papyrology team determined that it was not a duplicate of an existing work, meaning that the scroll contained never-before-seen text from antiquity.

What did it say? As the Vesuvius Challenge website cheekily put it, they found a “2000-year-old blog post about how to enjoy life.” The big theme was pleasure, which, properly understood, was the highest good in Epicurean philosophy.

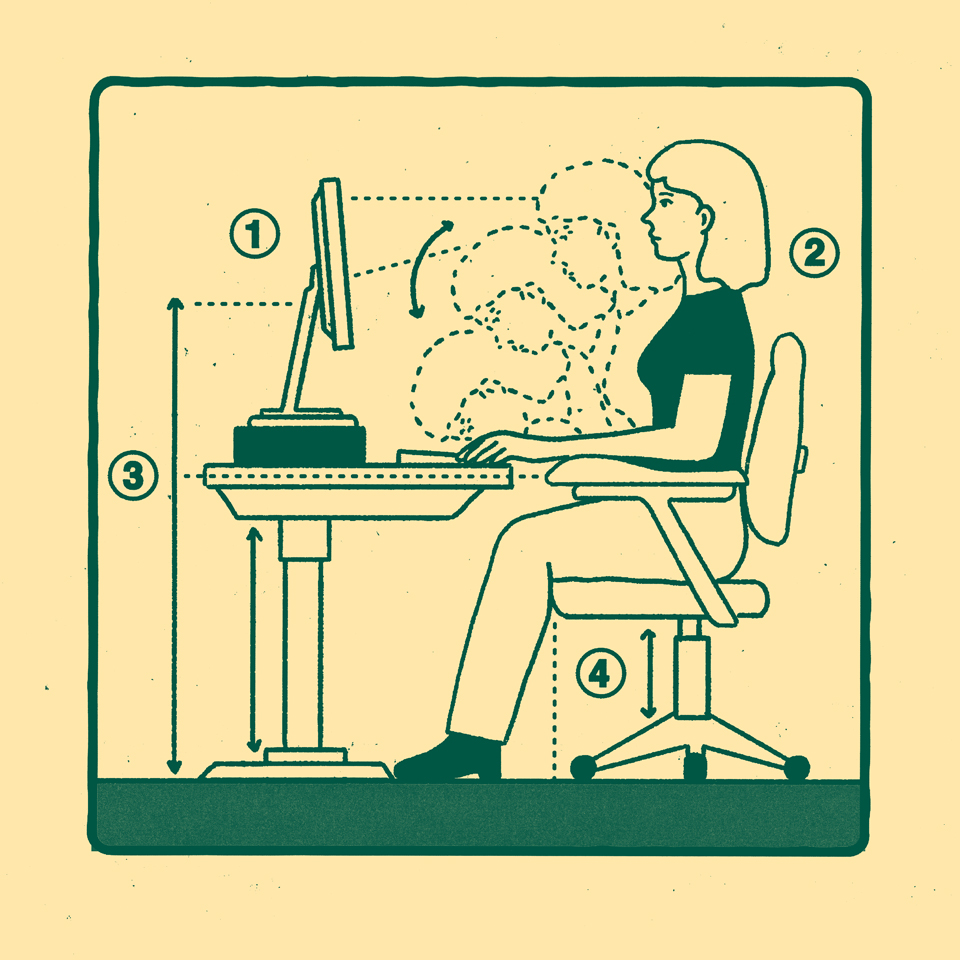

The arrival of widely accessible AI tools in the last ten years marks a turning point in the field of archaeology—arguably the most esoteric academic discipline. It’s old and literally dusty, and, traditionally, it requires vast input of attention hours for relatively modest outcomes. The questions are big: How did we get here? Why did cities start showing up 10,000 years ago? And they come with equally big implications for contemporary problems. But the pace of discovery and progress is torturously slow. That is until recently—thanks to developments like machine learning tools for analyzing satellite data and drone imagery, language models that sift through undeciphered scripts, and algorithms for reading crispy papyrus. These are the first steps in automating the most time-intensive aspects of archaeology with technology, giving way for archaeologists to do what humans do best: look at the bigger picture.

What we‘re getting wrong about our past

As Dr. Sarah Parcak wrote in her punchy archaeology newsletter, Future of Our Past, “Archaeology teaches us that we have been here before, many times, facing nearly identical problems.” The little fragments of pottery and papyrus that experts like her dig up out of the ground “show our resilience, our creativity, and our adaptability in the face of enormous challenges. People and their cultures can survive, and do, often in the most unlikely of ways.”

Recent findings suggest that our contemporary understanding of how we got here might be wrong. In the Dawn of Everything (2021), David Graeber and David Wengrow argue that many commonplace narratives about our deep past—the relative utopia of hunter-gatherer societies, on the one hand, and the Hobbesian vision of all against all on the other—have been debunked, or complicated, by the last decade of archaeological research. It simply wasn’t the case that all life prior to the advent of agriculture was confined to small bands wandering through the woods. And the arrival of farming didn’t necessarily “create” private property, as tempting as that theory might be.

“On the contrary,” Graeber and Wengrow write, “the world of hunter-gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms, far more than it does the drab abstractions of evolutionary theory… And far from setting class differences in stone, a surprising number of the world's earliest cities were organized on robustly egalitarian lines, with no need for authoritarian rulers, ambitious warrior-politicians, or even bossy administrators.”

AI tools can take care of vast amounts of legwork and enable the experts to do what they do best.

Graeber and Wengrow make the case that if our understanding of the past, and therefore of human nature, is slightly off, maybe we aren’t as locked in to the way things are now as it sometimes feels we are.

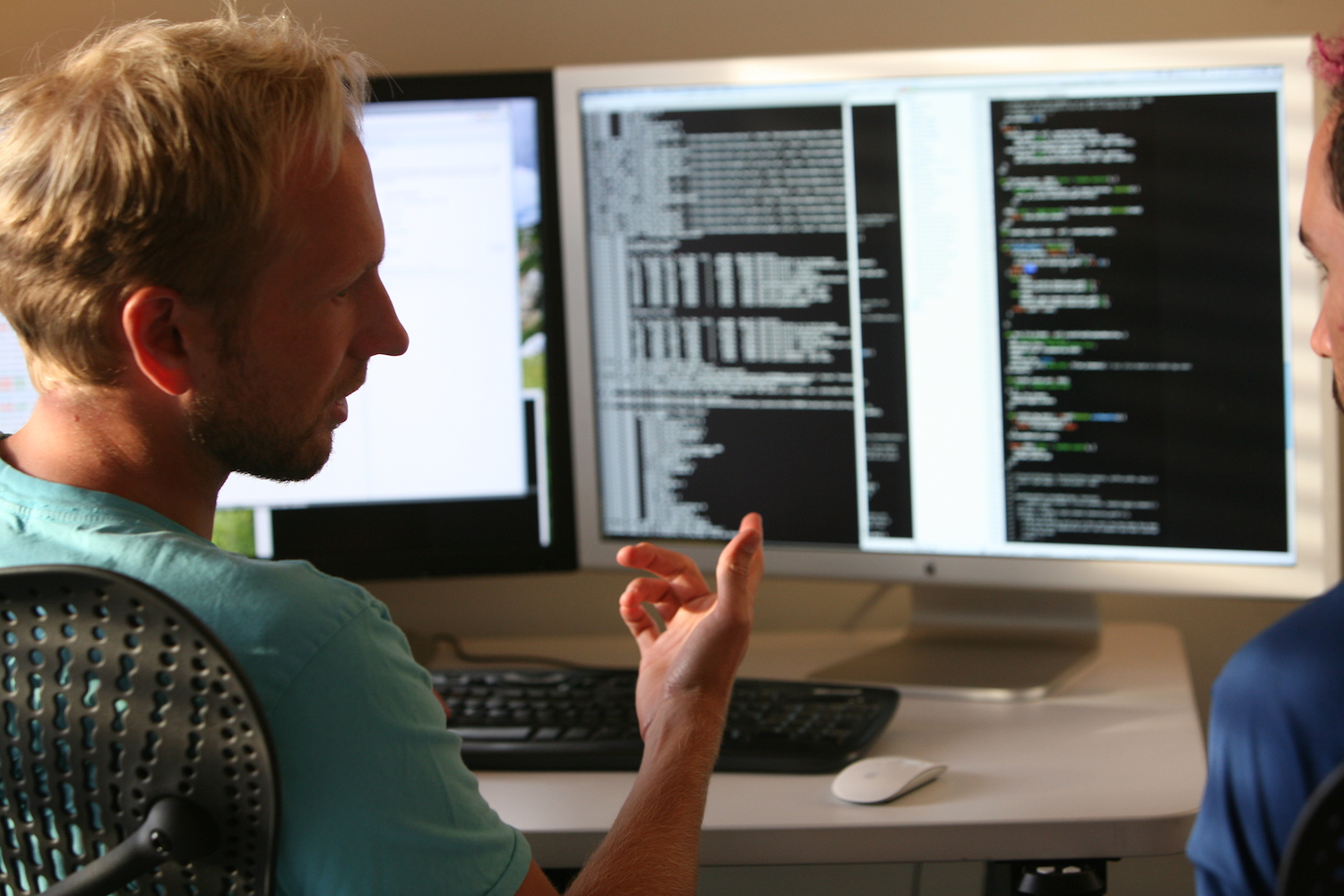

Big shifts in narrative like this require lots of evidence. Fifteen years ago the mood in archaeology was very different. The emphasis was niche. Young PhD candidates would focus intently on a small area and become experts at a very high level of detail. Then something changed. New and highly powered, if somewhat clumsy, AI tools began to automate the most labor-intensive busywork.

The dawn of a new kind of collaboration

Call it the dawn of the golden age of computational archaeology. Dr. Hector A. Orengo was one of the pioneers. He’s a professor at the Catalan Institute of Classical Archaeology where he applies machine learning to his research using cloud computing and big data. As an archaeologist, “your expertise is not to be able to identify little fragments of pottery,” he explained. “That can be done by a child. The expertise is to analyze: What is the significance?”

Two of Orengo’s most cited papers show a glimpse of what AI might be able to unlock here. In one, he took satellite data and trained an algorithm to identify archaeological mounds in the Cholistan Desert of Pakistan which might indicate Indus settlements from ca. 3300 to 1500 BC. Pre-AI, that would require having graduate students painstakingly pore over data, piling up man hours which means piling expenses. Also, it’s boring. The results spit out by the algorithm still require human verification. (Grad students can do that!) Then Orengo’s job is to interpret: What does the pattern of ancient settlements say about how they adapted to changes in their environment over time?

In the other paper, he trained another algorithm to scan high-resolution drone imagery and detect shards of pottery. This goes beyond saving a few grad student man-hours. The traditional method for pottery shard detection involves walking large tracts of land on foot, eyes trained on the ground, recording as you go. Using photogrammetry—taking measurements from photos—with geospatial analysis run off the Google Earth Engine, Orengo was able to dramatically reduce the time it takes to analyze a given landscape, proving that AI tools can take care of vast amounts of legwork, and enable the experts to do what they do best.

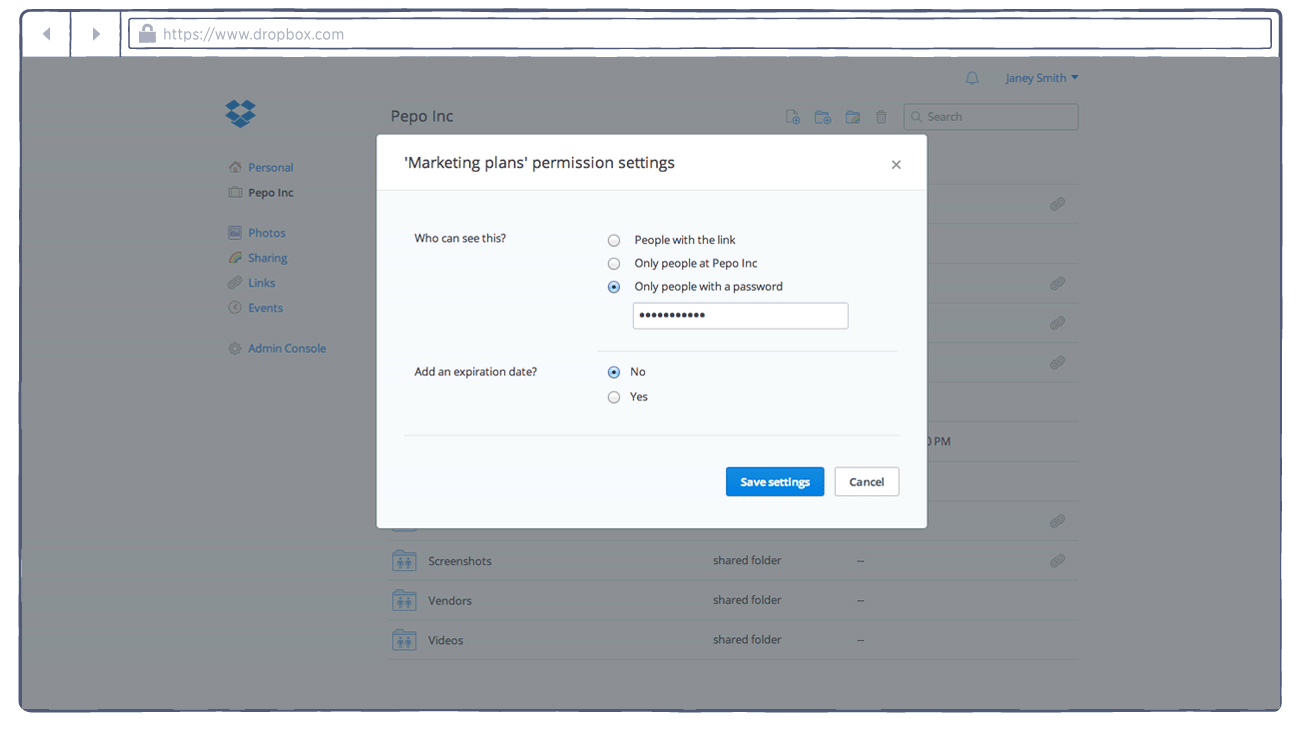

The dawn of computational archaeology is also the dawn of a new kind of collaboration. A team of researchers from the University of Bologna developed a human + AI workflow for discovering new archaeological sites. The model predicts sites with 80% accuracy on its own and becomes even more precise with a human expert. Keeping the human in the loop is essential, they argue. This also points to one of the stickiest problems with using AI to solve complex problems in the material world. The level of sophistication required both from a computer science perspective and from an archaeological perspective means that progress so far hasn’t been as rapid as in other areas of AI application. Plus, as Orengo drily mentioned, “You don't get into archaeology because you want to make money.”

The machine learning technology is both extremely powerful and relatively simple—not unlike the hot dog/not hot dog app from HBO’s Silicon Valley. (Orengo calls it “shooting flies with cannons.”) Yet while flashier generative AI tools have been getting their makers in hot water for misunderstanding basic things about human history, these image recognition algorithms may have a more immediate chance of helping us understand ourselves and where we came from.

Automating the legwork

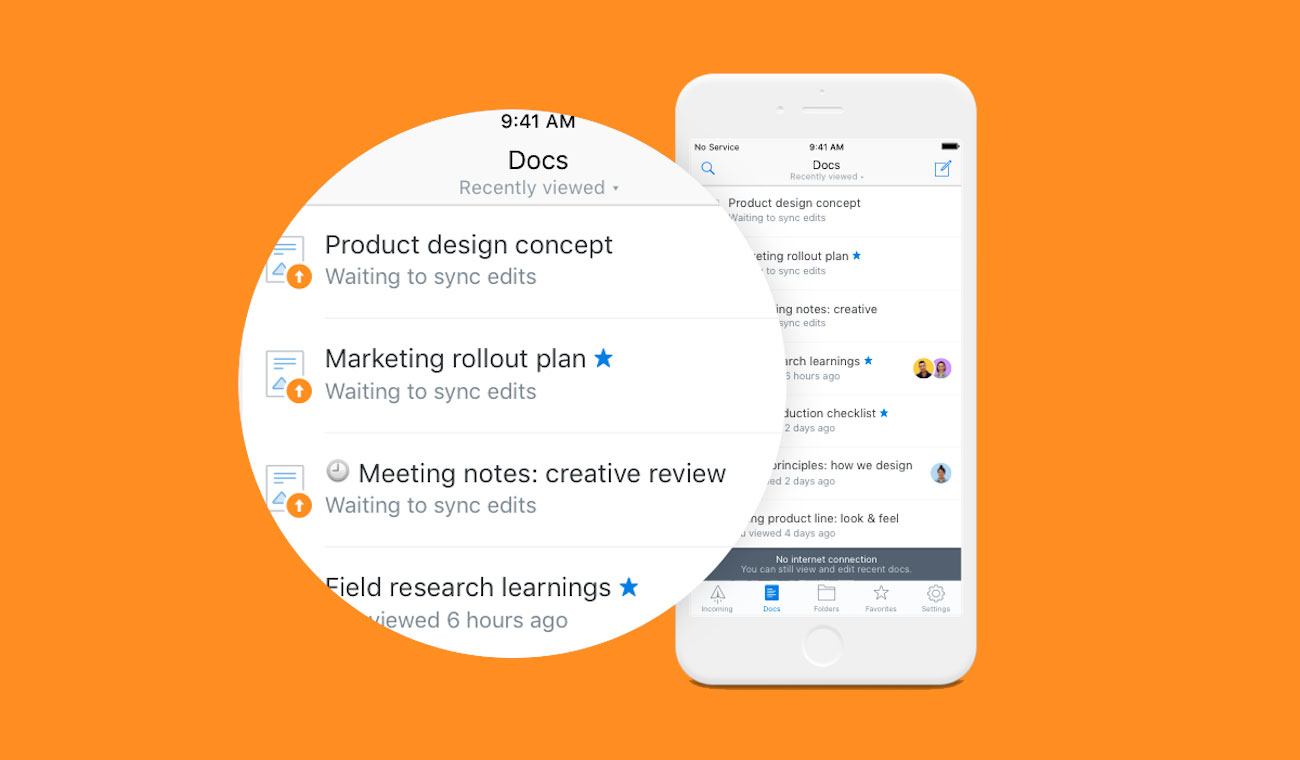

They can also help us figure out what to do next. Dr. Iris Kramer has leveraged her expertise in computational archaeology to break out of academia and start a company—Arch AI—where she’s essentially building a Google Maps for everything beneath the surface. It got her on the Forbes 30 Under 30 list for Europe and Tedx Talk. It also caught the attention of the United Kingdom’s Forestry Commission.

England wants to increase its woodlands from 14.5% to 16.5% by 2050. (For context, the European average is 44%. By comparison, England is bald.) Two percent is more than half a million acres. Rewilding land, regenerating biodiversity, re-meandering rivers to prevent flooding, reintroducing salt marshes to sequester carbon—these are all really hard to pull off. Especially in the UK where people are extra particular about what’s going on in their backyard. The trick to reintroducing woodland is to place it in an area that was woodland not too long ago.

The dawn of computational archeaology is also the dawn of a new kind of collaboration.

This required Kramer to pivot and begin using machine learning to scan old maps from the turn of the century. “Instead of just doing archeological site detections, we're now modeling the entire historic environment in the landscape,” Kramer said. “We know exactly where woodlands used to be and those locations are more likely to sustainably grow back because the seed banks and the mushrooms are still in the ground.” (Fungi are essential to healthy forests.)

Commercial applications for archaeology aren’t many—although Orengo has helped large hydroelectric companies place power lines. Kramer sees an opportunity for Arch AI to assist in the housing development process in the UK—which often gets bogged down in the approval process. It’s essential, with any new buildings, to avoid historically significant sites.

“Development needs to be sustainable,” Kramer said. But, “I'm also keen for development to speed up because people don't have enough houses in the UK. There's a massive housing crisis. So it's important that places are being built faster through understanding risk at an earlier stage.” There’s something very interesting happening here: Kramer is applying a niche technology in a niche research field and finding out that it might be useful in solving some of the biggest issues we’re facing in the present—another reason this is an exciting moment for archaeology.

But even just within academia, the old methods are getting a turbo boost from these technologies. Automating that time-intensive legwork opens up the field to new possibilities and allows the experts to return to unsolved mysteries with increased processing power. “We have lost the big picture,” Orengo said. “We have lost the beautiful narratives… the big questions, like, how do civilizations start? What is the origin of urbanism? In order to address these questions it is absolutely necessary to take a new approach.”

From that perspective, AI might be giving archaeologists a simpler gift: the time to do the actual work of archaeology—interpreting evidence, reexamining dusty old narratives, and seeking out new ones.

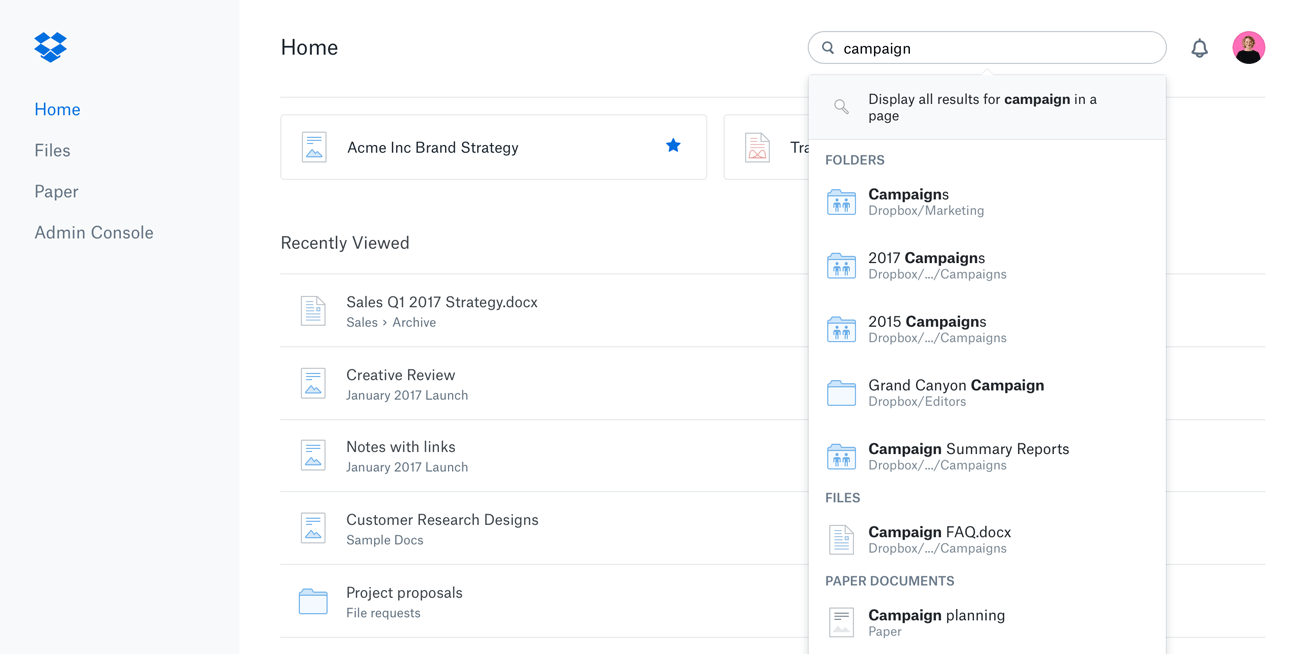

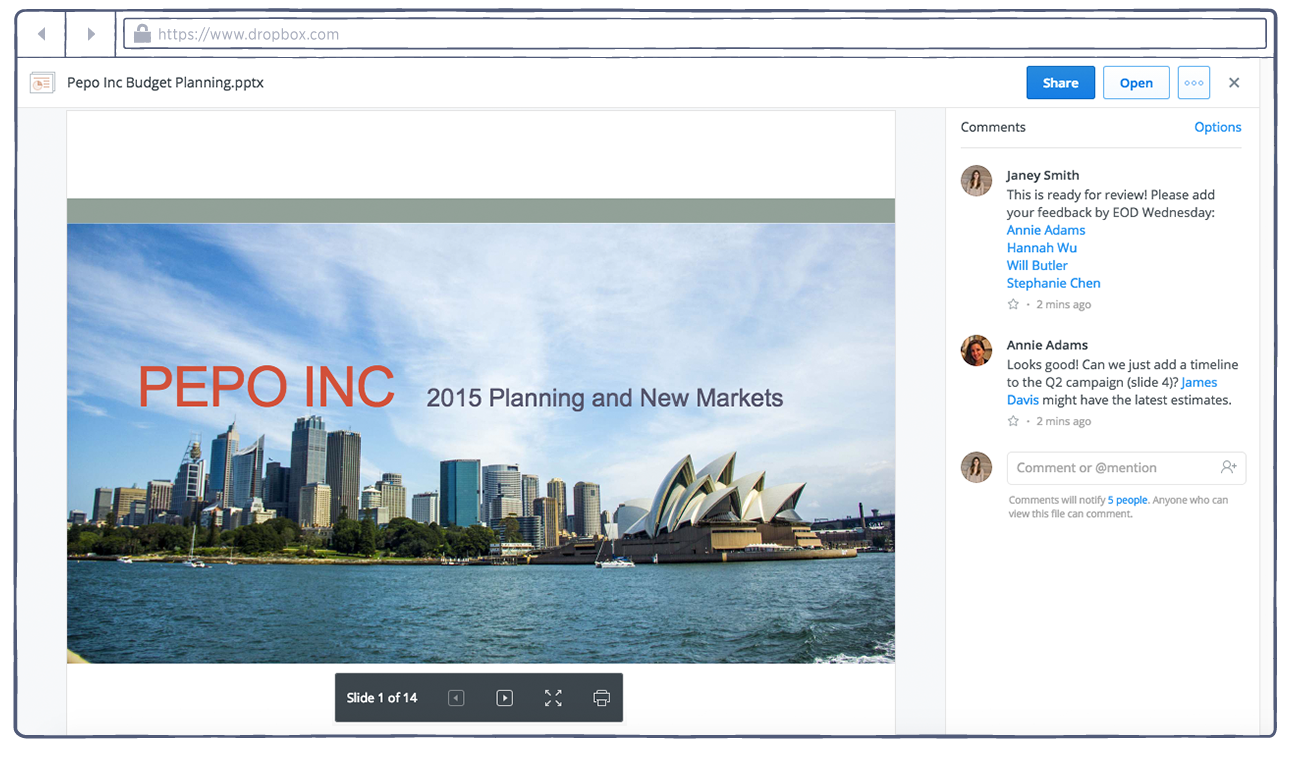

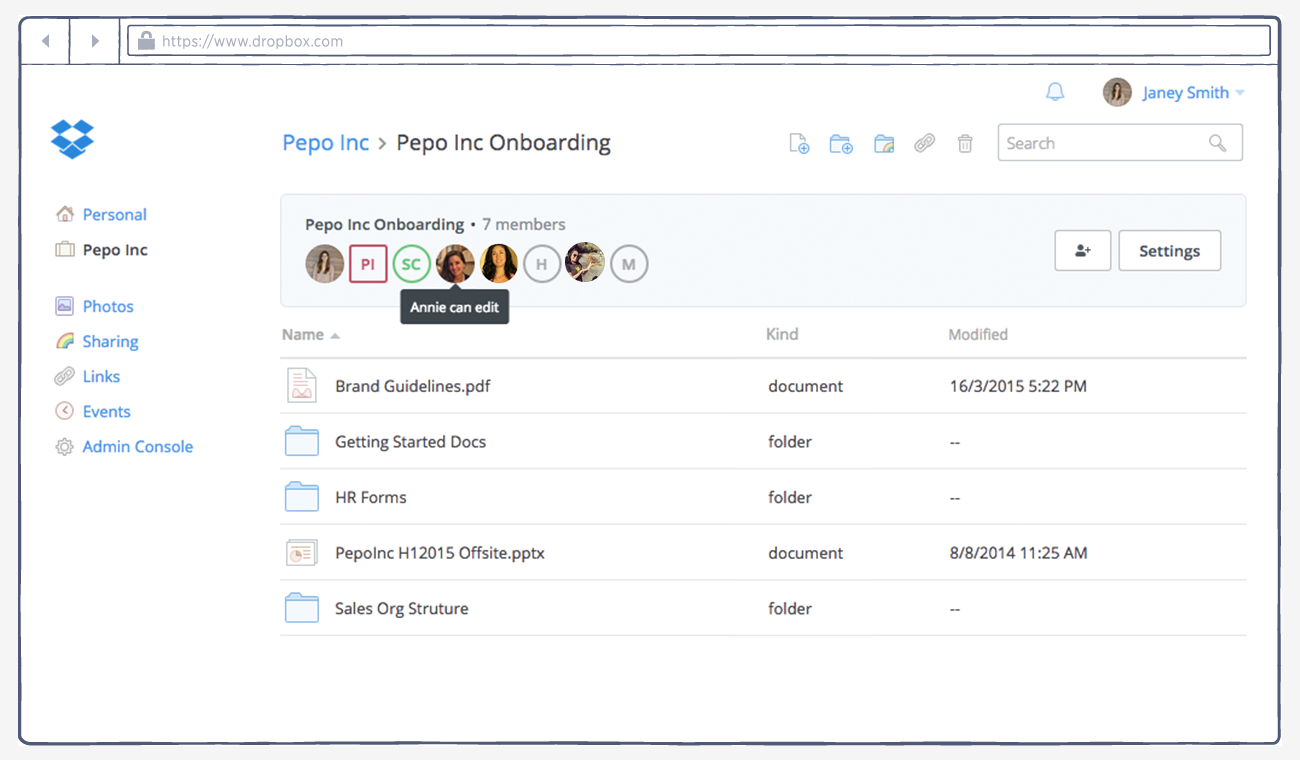

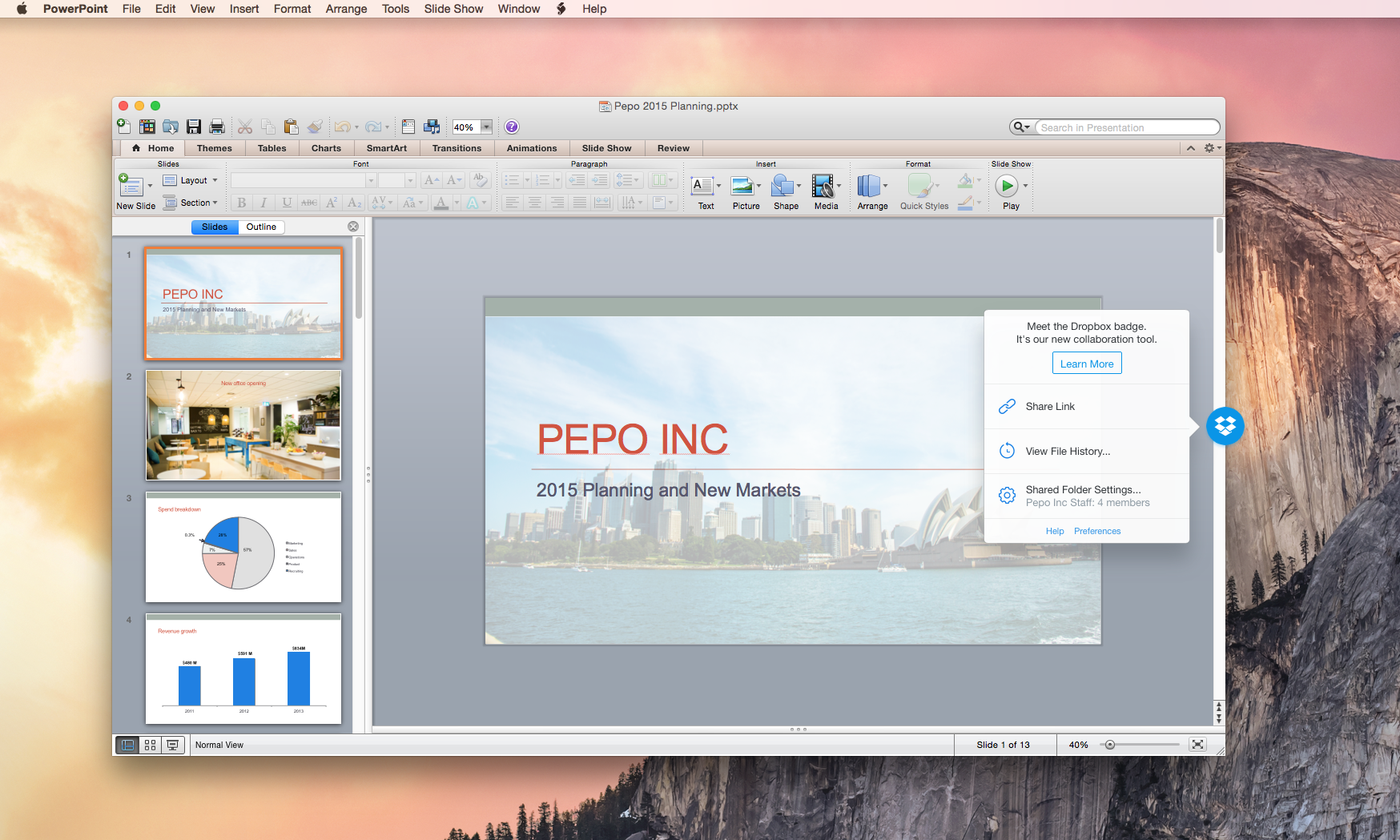

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_wide%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/blog%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_wide%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/1080x1080%20(1).webp)

.gif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)