.png/_jcr_content/renditions/blog%20(1).webp)

How AI is solving a murky problem for this beachside community

Published on September 18, 2024

In California's Padaro Beach, AI is used to spot sharks in the water. As human and wildlife habitats increasingly overlap, the data collected from emerging tech could help keep both parties safe.

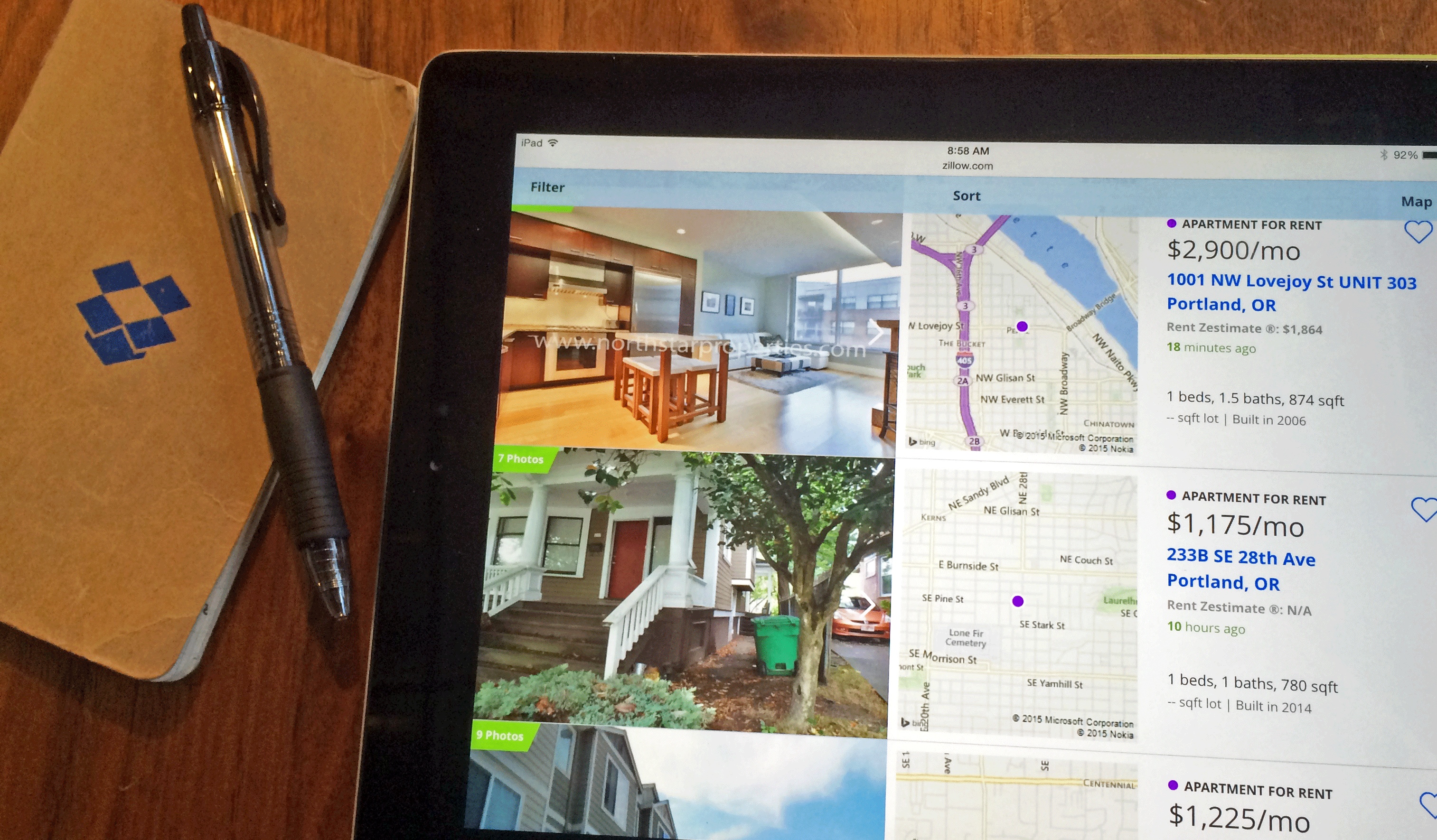

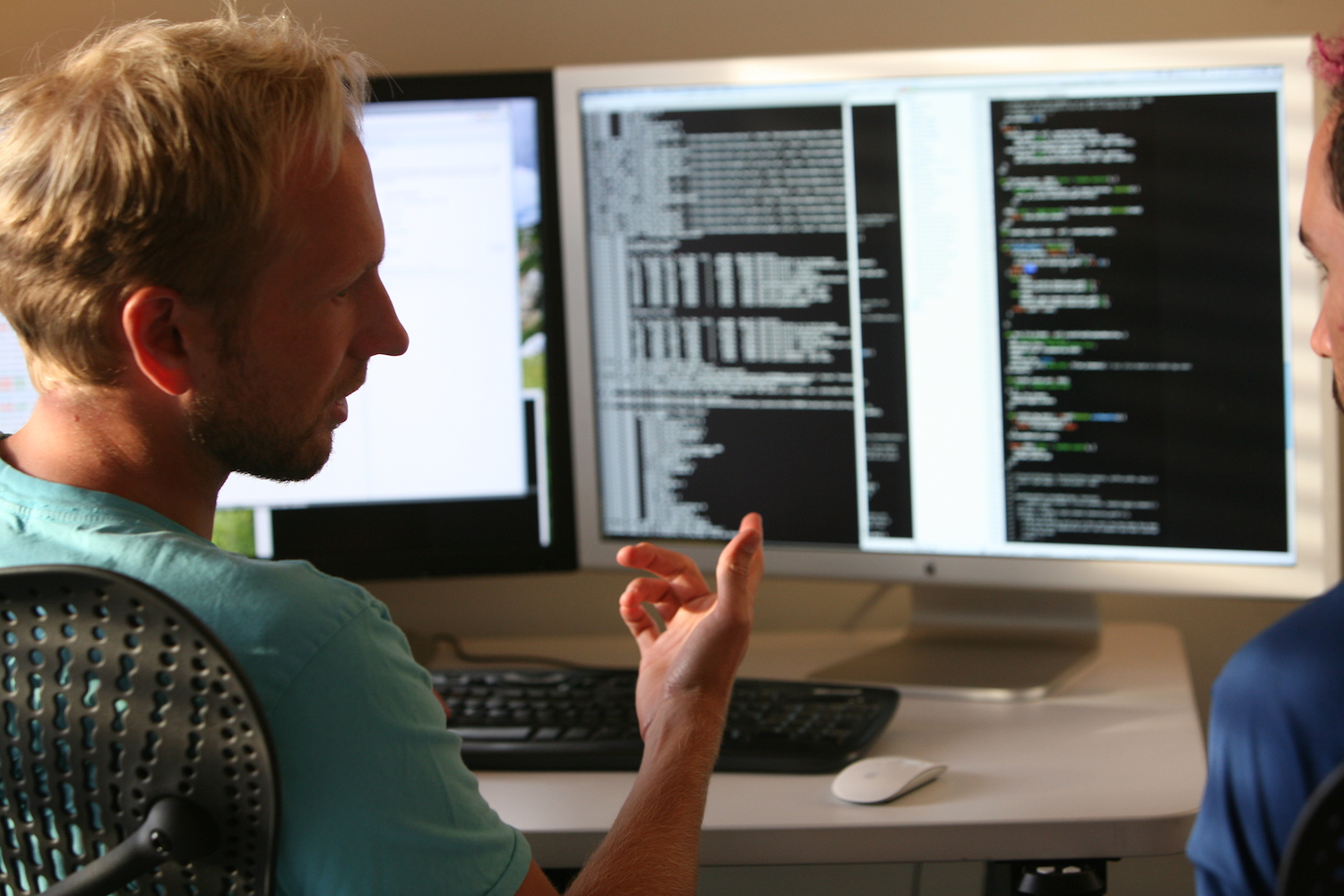

It was a July day four years ago when Chris Keet chose to buck tradition because of sharks. For two decades the founder of Surf Happens, a surf store that puts on lessons and camps on Padaro Beach, near Santa Barbara, California, had kept up a summer custom of having campers dive for sand dollars. But when he received a text notification that nine juvenile white sharks were found swimming offshore, he decided against it.

“Even though the sharks aren’t aggressive,” he recounted for the New York Times, “it just takes one.”

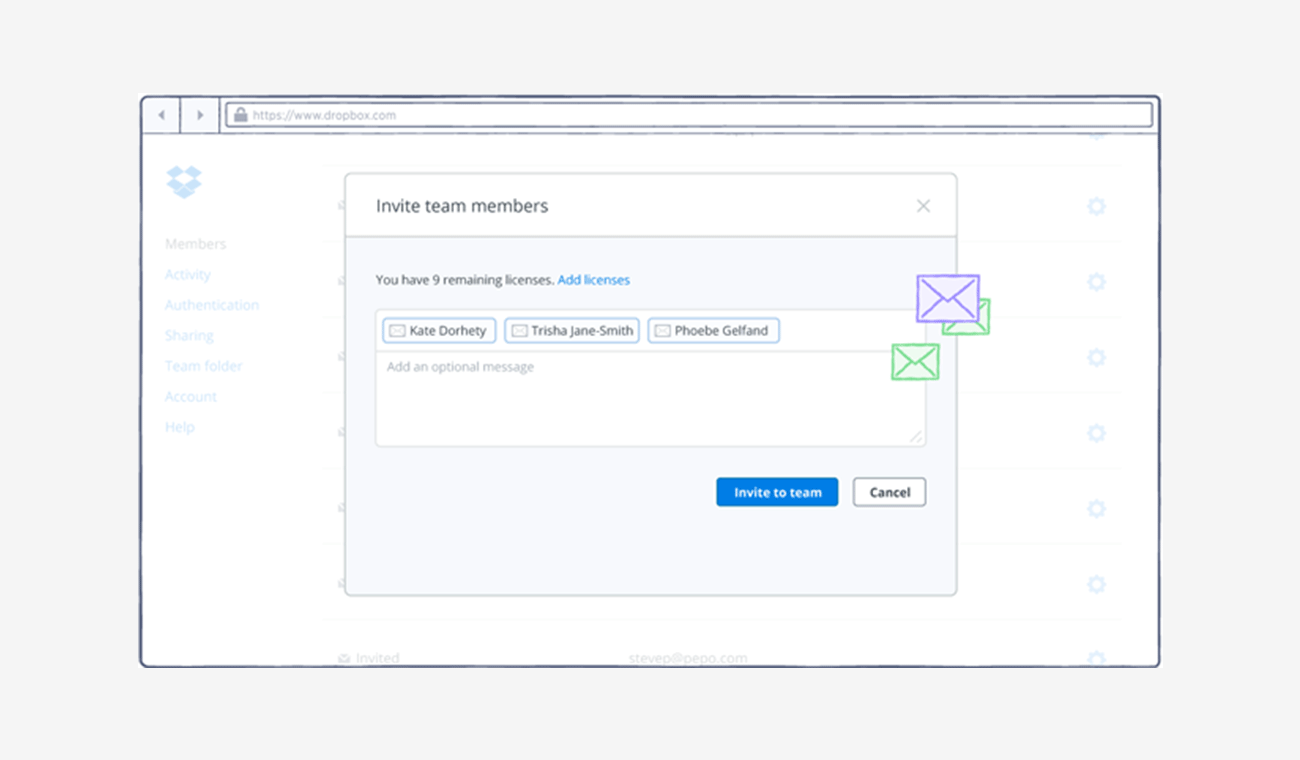

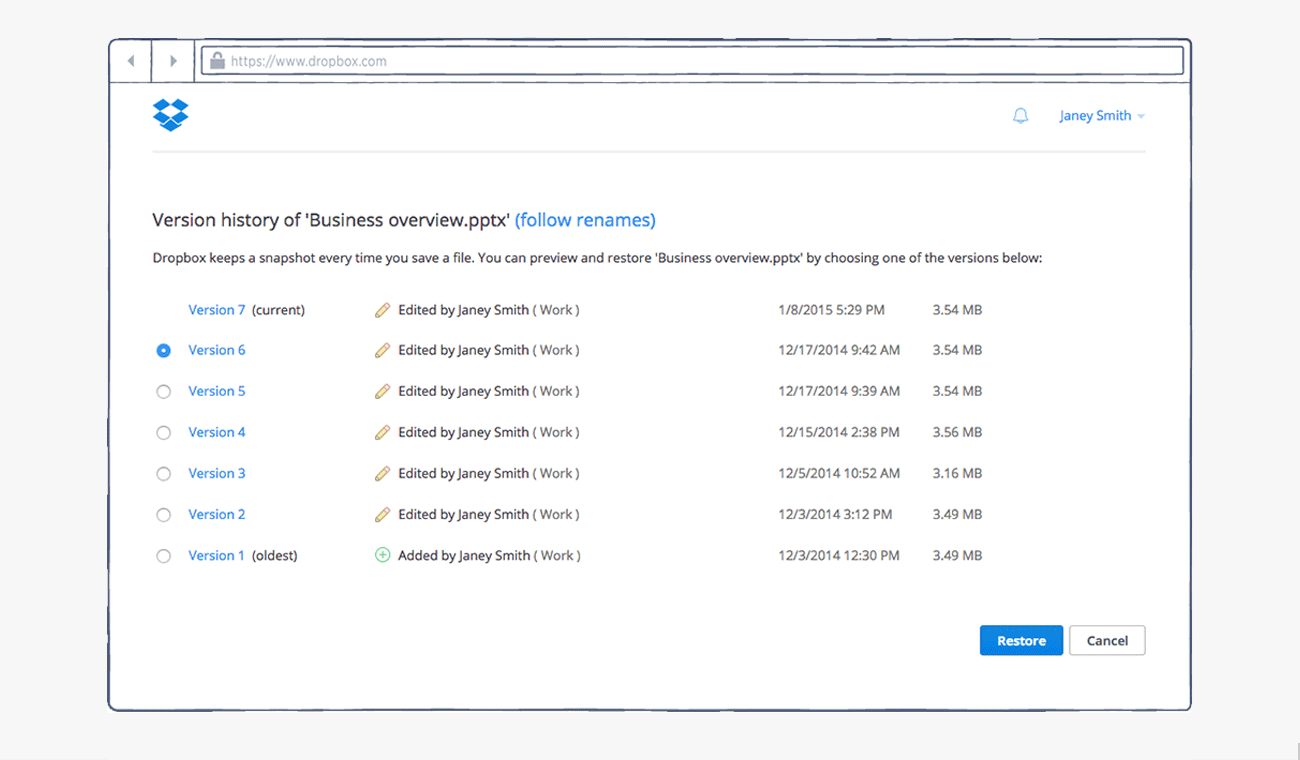

The notification came courtesy of SharkEye, a research initiative and text-alert system for Padaro Beach, a stretch of sand not far from the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, which develops and oversees the system from its headquarters at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Researchers with SharkEye fly drones over tracts of the beach, capturing camera and video footage. The film is then viewed by human analysts, who decipher what they’re seeing in the pictures. Sometimes the images show dolphins. Other times, it’s large patches of kelp. But in some of those images, the outlines and fins of white sharks are clearly visible.

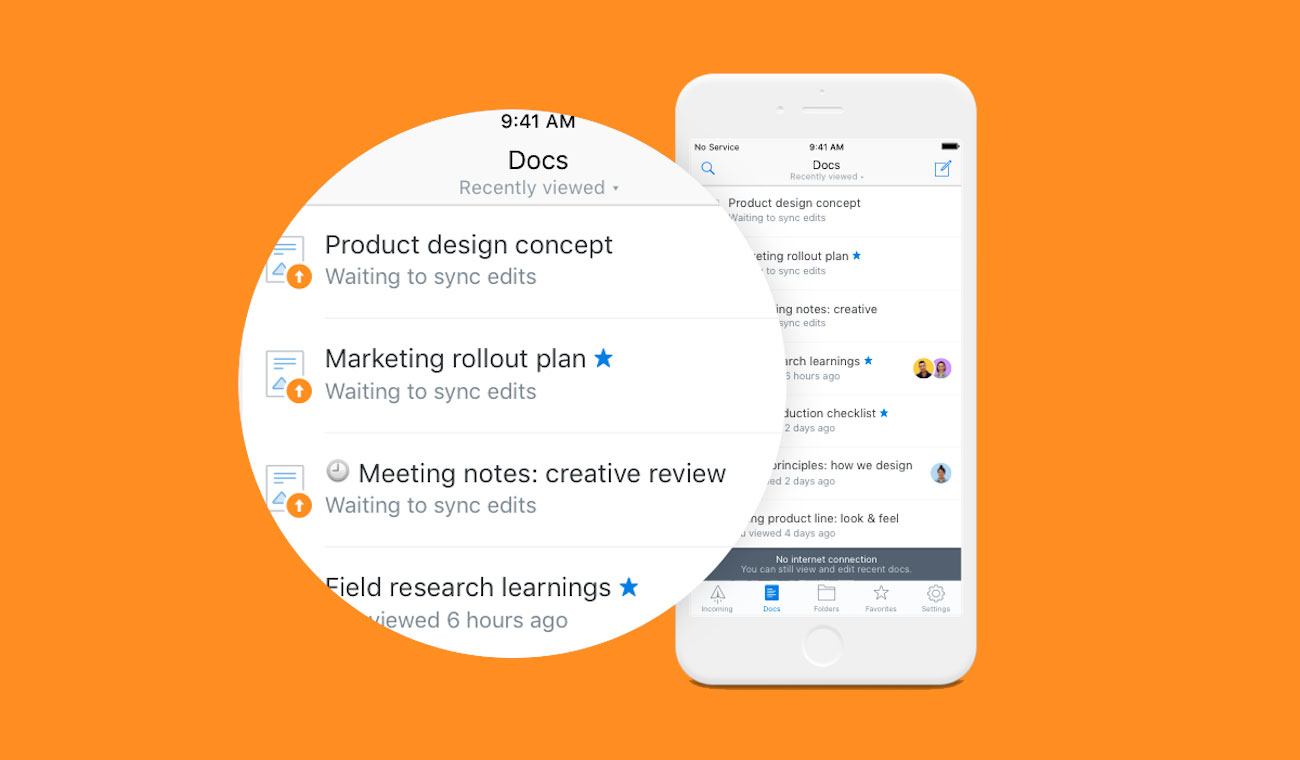

When the program detects sharks in Padaro Beach waters, SharkEye will push a notification to the mobile devices of people who have opted into alerts, as Keet had the day he decided against taking his campers out to dig for sand dollars.

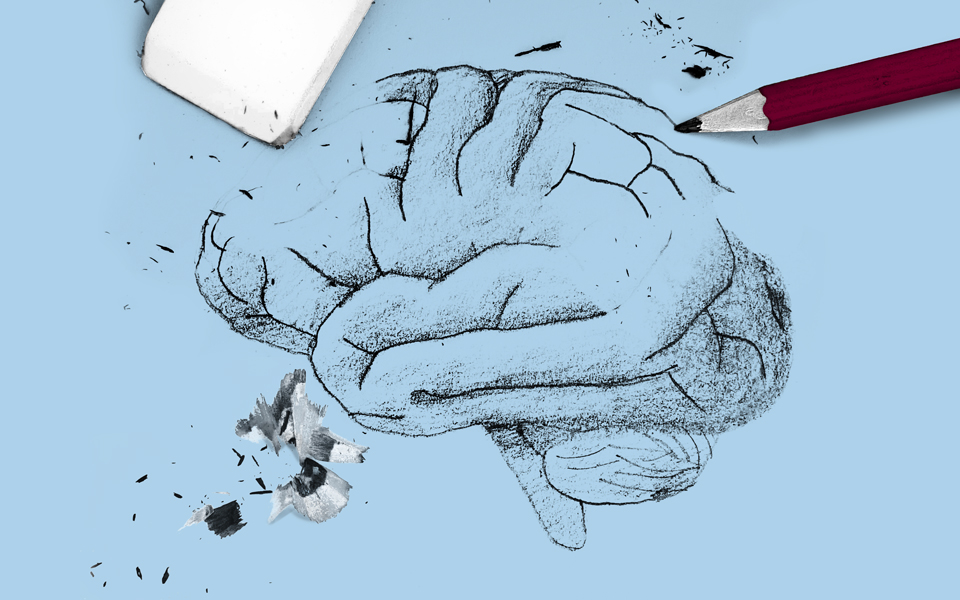

To date, SharkEye has largely relied on humans to identify sharks beneath the waves. But for close to five years, the company’s project scientists have been feeding its video footage into a machine learning model to train a computer to detect sharks and distinguish them from other objects commonly found in the waters of the Pacific Ocean. As of this summer, the SharkEye team began working with a new machine learning model they developed in-house, one that might take its work in a new direction by answering one simple question: Can artificial intelligence spot sharks better than the naked eye?

“We’ve actually realized that some things the AI is identifying are sharks that we missed on the first go,” says Neil Nathan, the project scientist who heads up SharkEye. It turns out, humans are limited in their ability to confidently spot sharks well, and while shark attacks in U.S. waters are rare, all it takes is one shark to spoil a swimmer’s afternoon. (In California, two fatal attacks have taken place in the last four years: one in 2020, when a surfer was killed, and another in 2021 after a shark went for a man boogie boarding.)

That’s where AI plays a crucial role in SharkEye’s initiative—by leveraging machine learning, the company can better spot sharks in murky waters, not only gaining more insight into shark behavior but also helping the local community stay informed of their activity. As touchpoints between humans and wildlife continue to increase, the use of AI in tools like SharkEye demonstrates the power of technology in managing these interactions far beyond the beach.

Surveillance is not only good for studying ecology; it can also aid people looking to more responsibly share the ocean with creatures like sharks.

Taking the guesswork out of shark spotting

“Right in our backyard is one of the more active juvenile white shark sites in California,” says Neil Nathan, the project scientist who heads up SharkEye. “A lot of the work we do has actually been to better increase our understanding of juvenile white shark aggregations and their population ecology.” After Padaro Beach locals heard about what the SharkEye team was doing—or, in some cases, literally saw drones flying overhead—they wanted in on the data, too. “We did hear some interest from the community that data like this would help them more,” says Nathan. Surveillance is not only good for studying ecology; it can also aid people looking to more responsibly share the ocean with creatures like sharks.

Juvenile white sharks ranging in length from five-feet to 10-feet are usually found off Padaro Beach. It’s where they grow into adolescence, feeding on species of benthic fish and other species that congregate on the ocean floor—like rays—before they develop a palate for marine mammals found in the open ocean.

In recent years, though, warmer waters off the coast of Southern California have lured great whites farther north from their usual swimming holes near Baja California. The same summer Keet decided against the traditional sand dollar dive, a woman swimming at Padaro Beach was bitten by a shark. And with rising congregations of white sharks off Padaro Beach, community members wanted to know when sharks were hanging out near the beach. “Some just prefer to know, especially when their kids are out there,” says Nathan.

SharkEye researchers run flights from about April through the end of the summer, when white sharks are at their most active, just before they dip back down south for warmer waters as winter approaches. The drones used are DJI Mavic 2 Pro models—pricey at more than $2,000, but nonetheless consumer-level quadcopters. One flies autonomously, preprogrammed to soar 40 meters overhead over given transects of beach, with a camera pointed 90-degrees downward. Humans man the other quadcopter. Captured video footage is immediately analyzed by project staff after survey flights are finished, at which point a count of uniquely identifiable sharks is taken.

With nearly five years of data, training artificial intelligence to do the same type of work was fairly simple, according to Nathan. Using the YOLOv8 object-detection model, the computer vision has learned what a shark looks like, not only based on its outline, but also on its length and overall size.

Many times the juvenile sharks off Padaro Beach swim no deeper than six feet from the surface. But when they dive down deeper, swim close to other mammals or objects, or when their shapes are obscured by glare or choppy waves, white sharks can be difficult to spot.

“We’ve found that humans aren’t really going to be able to spot them or be able to confidently say that something they see is a shark,” Nathan says. “But when we’ve run our new model against some of this historical data, we have seen a few instances of the model identifying sharks that were missed by human analysis the first time.”

The new AI model might confuse a specific piece of kelp, for example, with a low confidence. But when the image is that of a legitimate shark, it picks it up as much as 97 percent of the time.

The increasing presence [of sharks] in shallower waters is also indicative of a larger upward trend of wildlife and human environments encroaching upon each other.

A smarter way to enjoy the great outdoors

Though the specter of sharks often provokes hysteria—merely mentioning a white shark conjures images of the 25-foot beast from Jaws—their role as apex predators are often underappreciated. Sharks are a crucial part of marine ecosystems. By feeding on medium-size fish, sharks ensure that stable populations of smaller fish, which typically act as coral reef cleaners, are maintained.

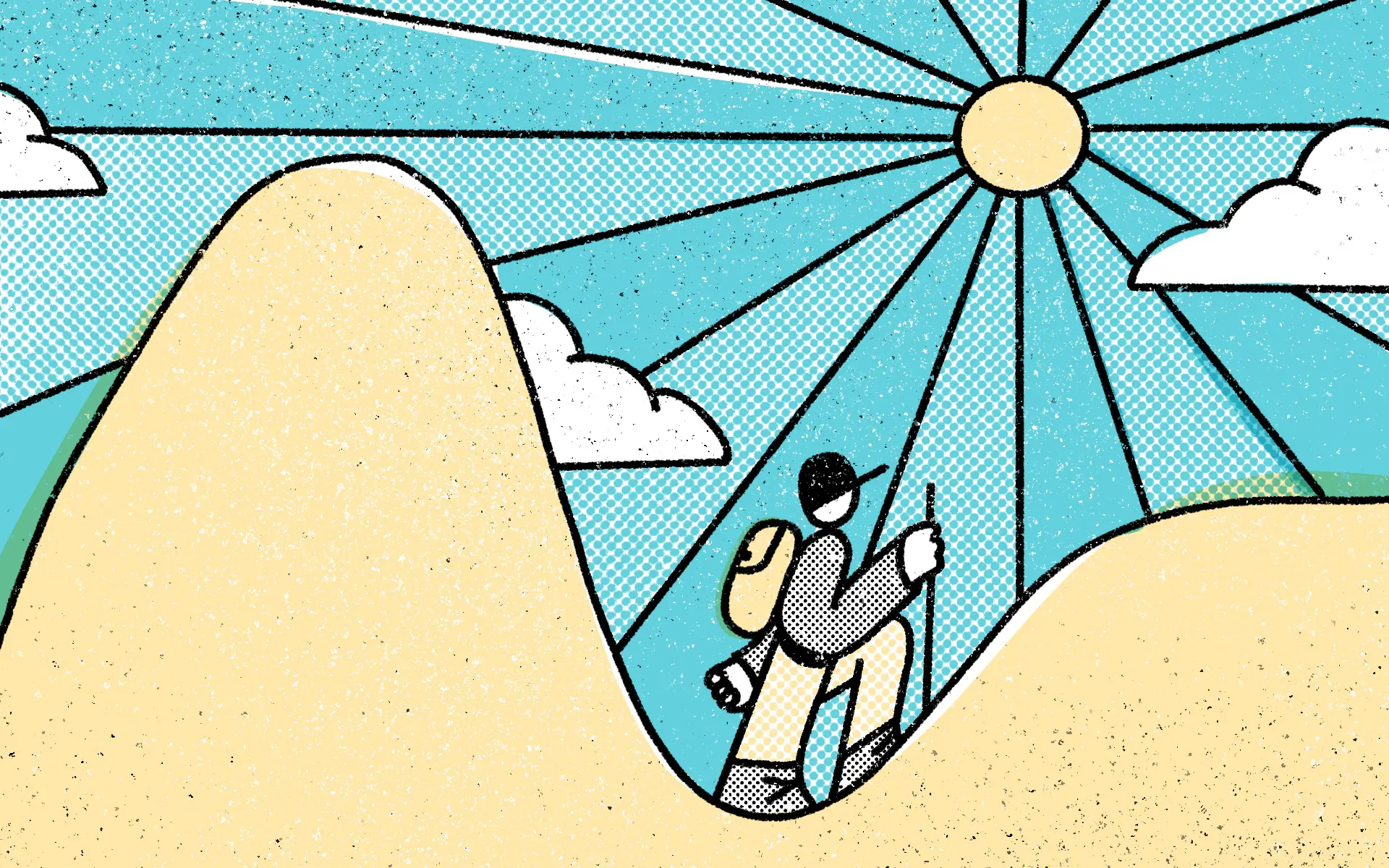

While shark fearmongering is arguably overblown, it’s still important for beachgoers to exercise caution where sharks are known to be present. Their increasing presence in shallower waters is also indicative of a larger upward trend of wildlife and human environments encroaching upon each other.

“We have seen rising populations of sharks in California,” says Nathan. “We’ve also seen, especially since COVID, increasing numbers of humans using the water—surfing, swimming, paddleboarding.”

As the divide between human and wildlife habitats becomes fainter, tools like SharkEye can be used to keep people better informed so they can share the great outdoors responsibly and safely. Imagine a similar surveillance system implemented to help hikers know where bears, deer, and moose are residing along trail routes. Or a push notification that goes out to bird watchers keen on spotting a feathered friend but not interested in disturbing nesting grounds.

For now, Nathan and his colleagues maintain a watchful presence over Padaro Beach—where he says that despite more use of the water, there hasn’t been a rise in shark-on-human incidents. With SharkEye in the sky, of course, Nathan would know.

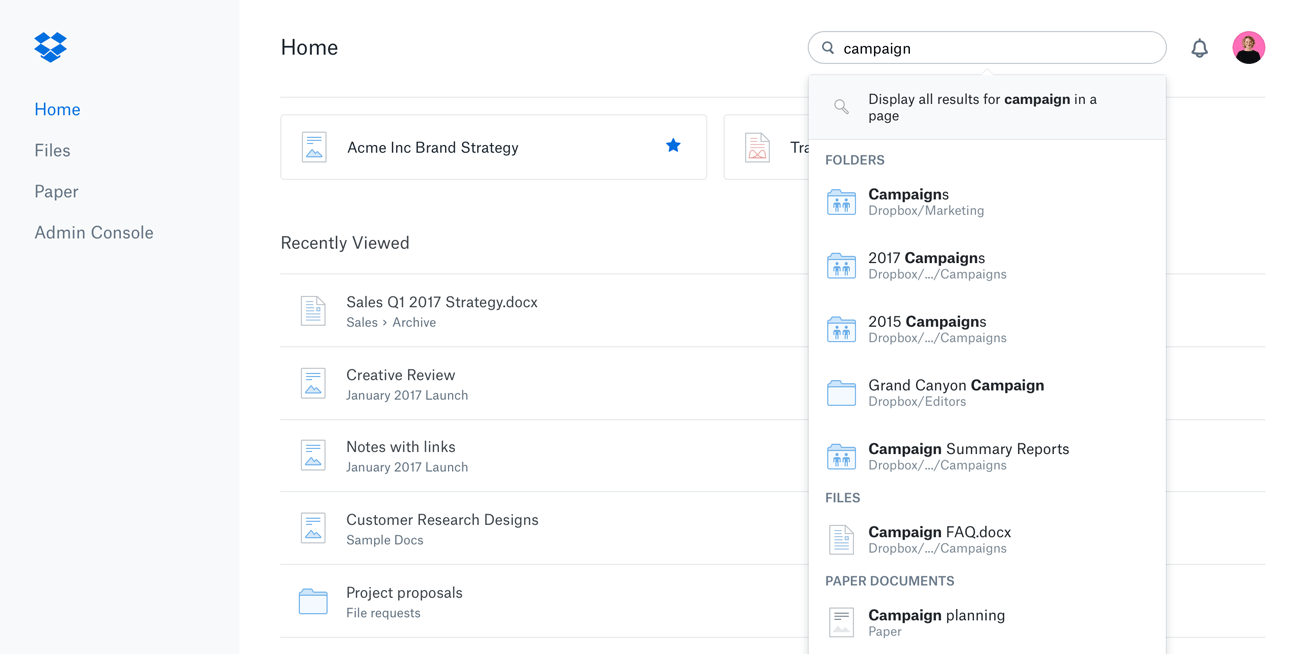

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_wide%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(3).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_wide%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/1080x1080%20(1).webp)

.gif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)