Why this attention expert says multitasking is the enemy of focus

Published on July 19, 2023

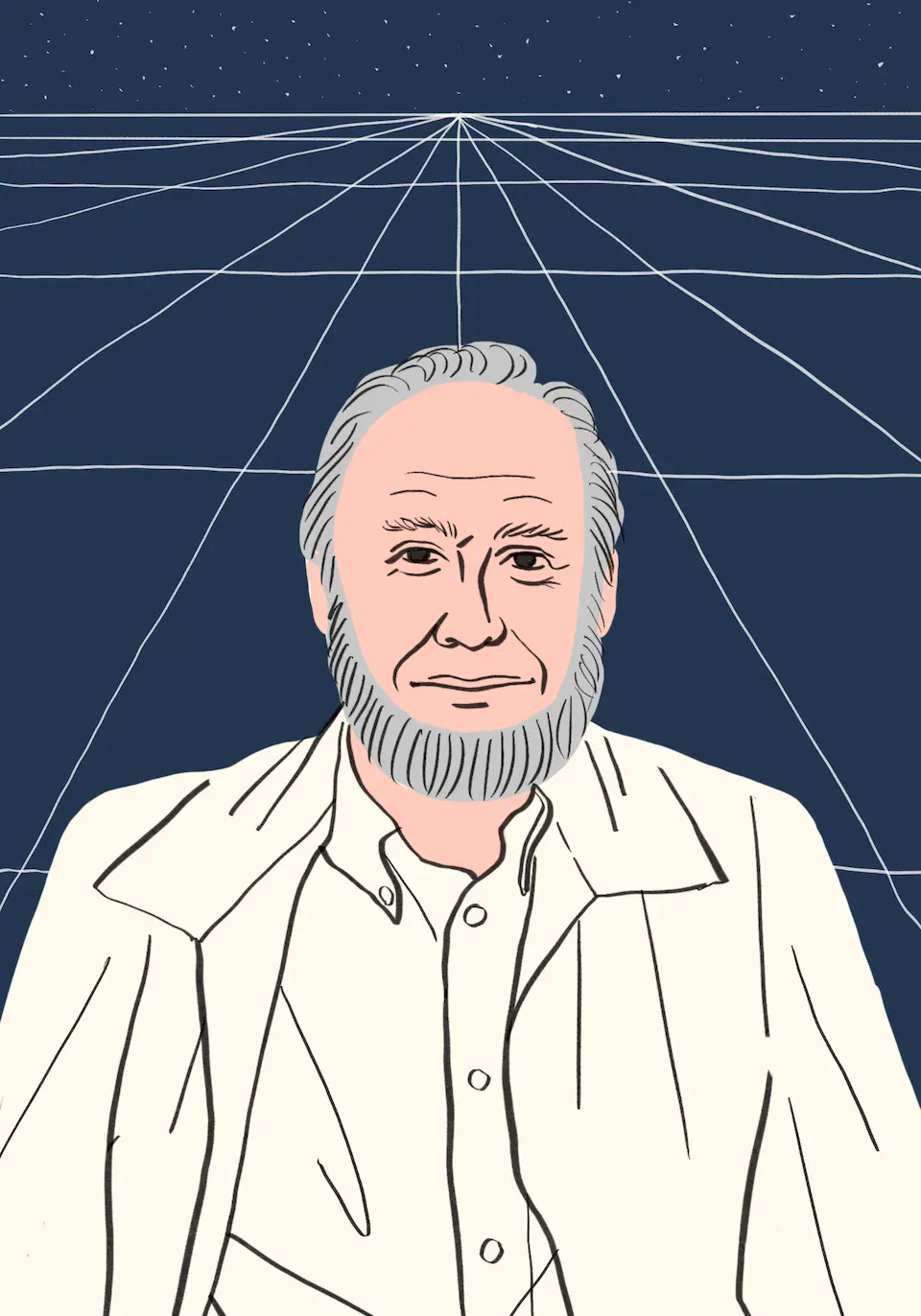

Paying attention to where you place your attention is a difficult feat in a digital world that’s designed to be distracting. But according to Dr. Gloria Mark, professor and researcher at the University of California in Irvine, it's actually the key to finding deep focus at work.

To help others better navigate this challenge, Dr. Mark wrote Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity. Published in January, it’s the culmination of over two decades spent studying the impact of digital media on people's lives. Dr. Mark spoke with Tiffani Jones Brown about the science of attention, the pitfalls of multitasking, and the potential for technology to support our focus.

How would you describe focus in relation to our attention spans?

Dr. Gloria Mark: Most people tend to think of attention as having two states: you're either focused or you're not focused. The reality is that it's a lot more nuanced than that. Instead of focus belonging to one, central, fixed place in the brain, we actually have three basic networks of attention working at any given time.

There's one in charge of selecting the information that we choose to focus on. And then there's another network which is responsible for vigilance—holding sustained attention on something. Then there's a third network that's involved in doing sort of defense work. It's filtering out peripheral information to prevent us from getting distracted.

When you’re focused, all three of those networks are able to do their job well. It's selecting, prioritizing what we want to work on. We can have sustained attention on something and we can filter out distractions.

“Instead of focus belonging to one, central, fixed place in the brain, we actually have three basic networks of attention.”

In your book, you talk about some of the common myths around focus. Can you discuss one of the myths and how to combat it?

One of the common narratives that we hear is that we should always strive to be focused, pack in as much as we can, and therefore be productive. But it's just not possible for people to hold sustained attention for long periods of time in the same way that we can't lift weights all day without getting exhausted.

It's really important to work in significant breaks to be able to refresh ourselves and replenish so that we can have better focus when we go back to [work]. People have a limited amount of attentional resources, and when we hold sustained focus for a long period of time, we drain those resources.

The best break is to actually go outside for 20 minutes. And the best thing of all is to be in nature, because we know that's the most restorative kind of break for people.

You’ve talked about how our attention spans have dipped quite a bit from around two and a half minutes to something like 47 seconds over the last decade when we're engaging with screens. What are the potential consequences of this collective dip?

We know that when people are shifting their attention rapidly—which is multitasking—it harms performance in several ways. Number one: people make more errors. There is a study done with doctors that shows that they make more prescribing errors when their attention is shifting.

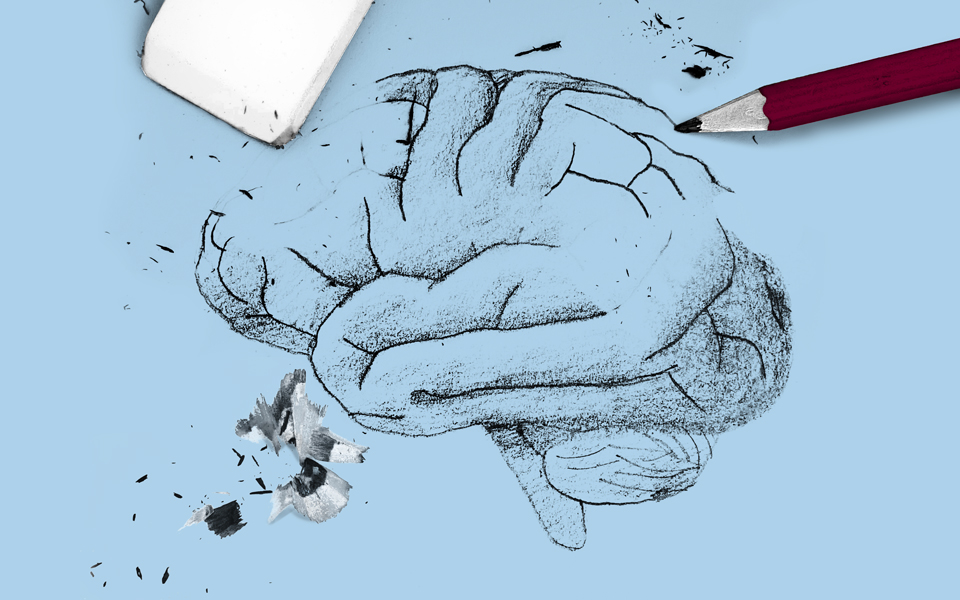

A second thing is that it slows people down. We think by shifting our attention, we're accomplishing more, right? [We think] we're getting to do work on more different things and faster, but there's a switch cost every time. Imagine you have a whiteboard in your mind, and that whiteboard holds a representation of the information we need in order to do a task. Then all of a sudden, we switch our attention and do something else—let's say email. It's like erasing that whiteboard and then writing up the new information.

The worst thing of all, in my view, is that switching our attention so fast causes stress. We know from decades of laboratory research that blood pressure rises. In my research in living laboratories, we see when people are wearing heart rate monitors, when they're switching their attention fast, their stress goes up.

“The best thing of all is to be in nature, because we know that's the most restorative kind of break for people.”

How can we gain agency over our attention?

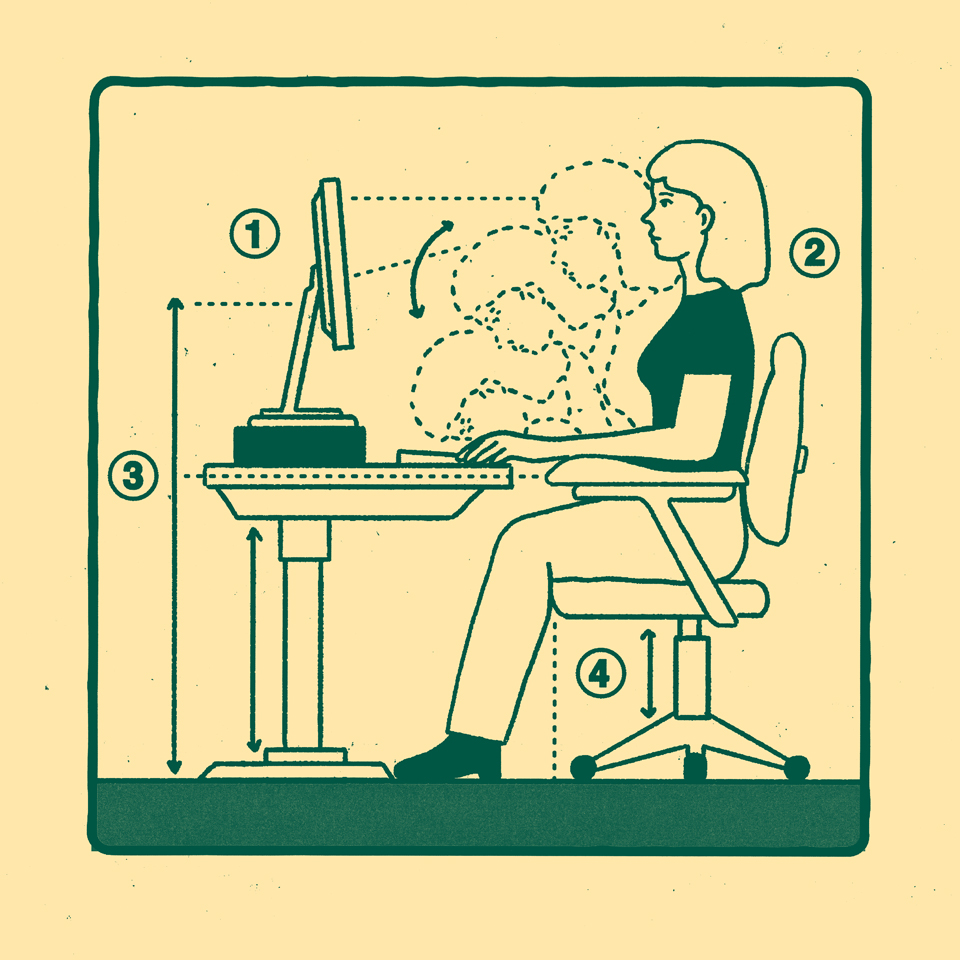

We do that by what I call meta awareness, which is being aware of what you're doing as it's unfolding. I picked this up during the pandemic. We were working at home and my university offered a course in mindfulness-based stress reduction about how to focus on the present. I realized we can do exactly the same thing when we're on our devices. We can learn how to focus on the present so that we can filter out all these other distractions.

When I have an urge [towards distraction], I probe myself: Why do I have this urge? Why do I need to check the news right now? It's usually because I'm bored or because I just want to procrastinate. [If] I face those reasons, I can become intentional. I can take action, and I can change. No person can hold long periods of sustained attention without taking a break and still expect performance to be high.

Once we’re more aware of our attention, how can we direct it towards deeper focus?

Attention is goal oriented. We direct our attention according to what our goal is. If my goal is to work on a report, that's where my attention goes. If my goal is to check social media, I have this urge to check social media. That's where my attention goes.

“No person can hold long periods of sustained attention without taking a break and still expect performance to be high.”

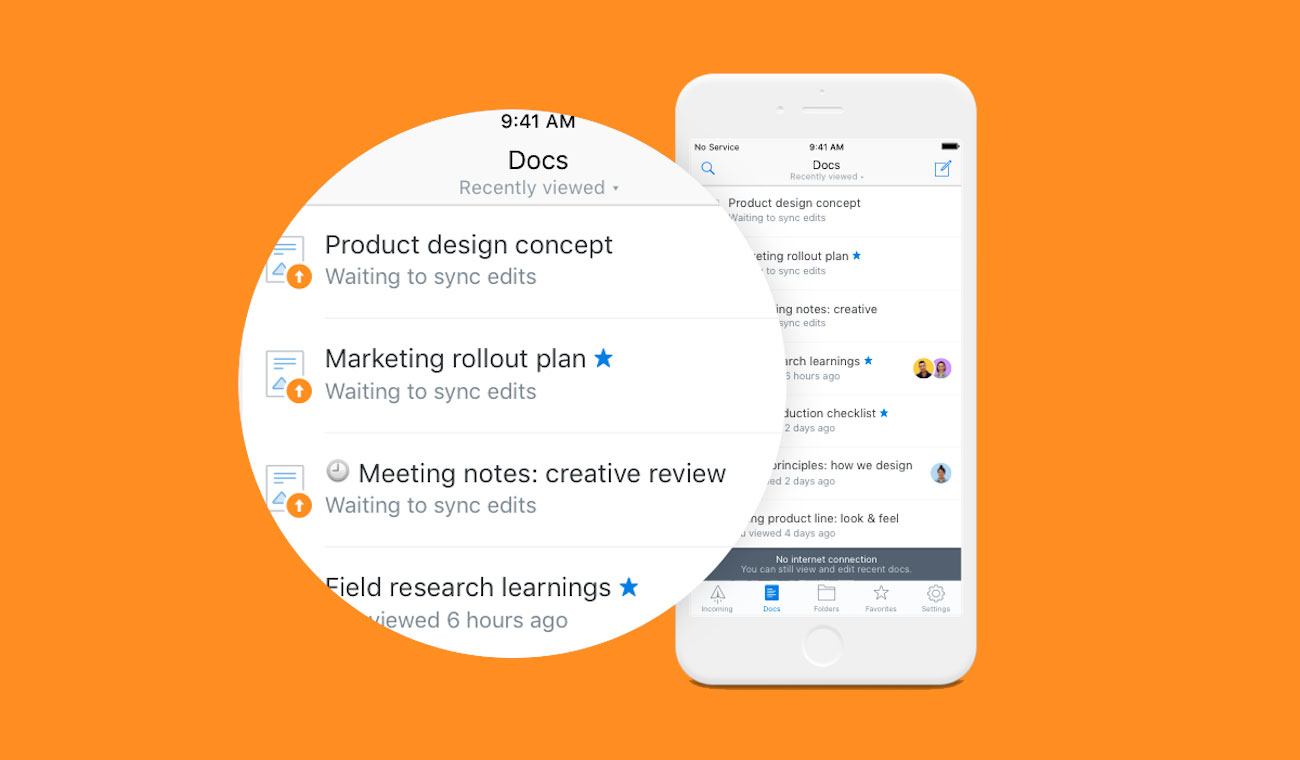

I've done some work with Alex Williams and colleagues at Microsoft Research on a very simple conversational agent that asks people at the beginning of the day, “What do you want to accomplish and how do you want to feel?” Simply asking these two questions helped people stay on track, because it brought goals to the forefront and helped direct attention.

Goals are dynamic. They fade in and out of our minds, and it's really important to keep reminding ourselves of what our goals are. Writing it on a piece of paper, having an audio voice memo—whatever it takes to keep reminding ourselves of what our goals are.

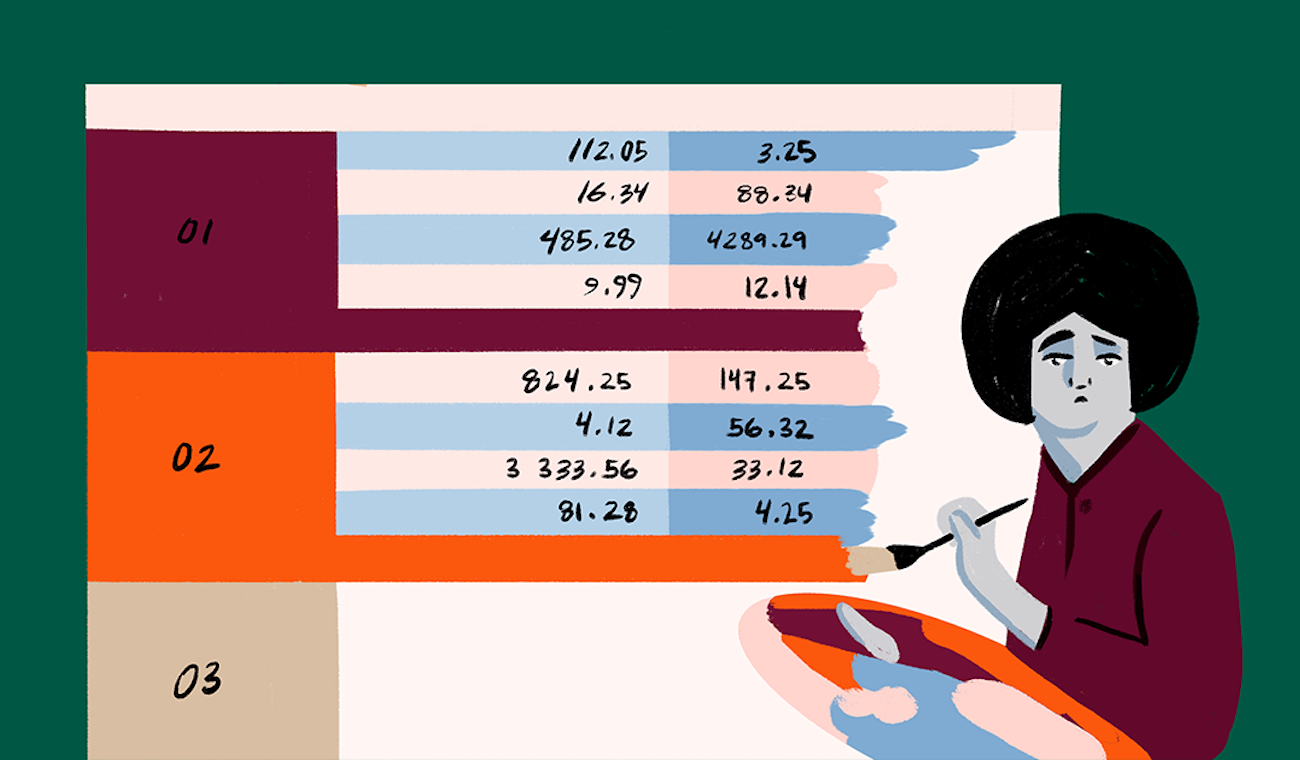

You’ve mentioned that technology both helps and hurts our focus. In what ways can it help?

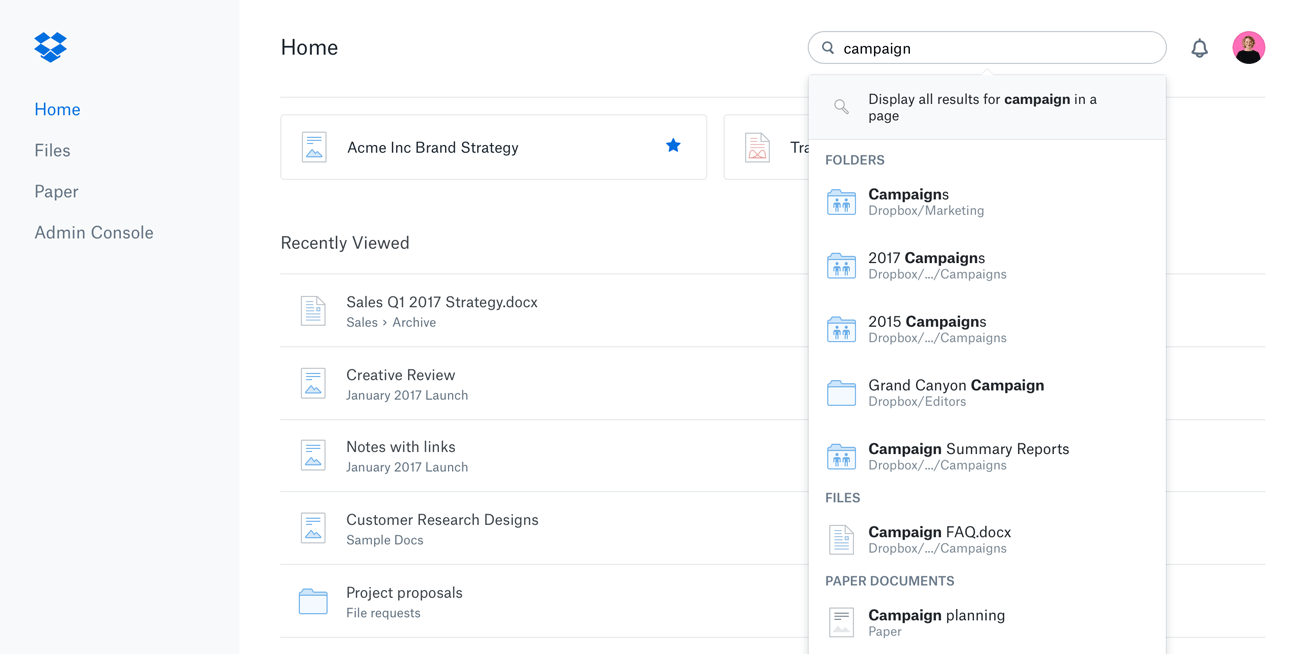

When we think about AI as a helper or as a coach, I think that there’s promise there. Imagine that we had a personal assistant who could help teach you this notion of meta awareness and understand when you're getting exhausted. It can nudge you—”Hey, don't you think it's time for a break?” If you're spending too much time on social media, it can coach you and say, “It's time to come back.”

The agent should not do all the work for you but learn about your behaviors, your mood, so that it can help you respond and adapt better to the environment. It should serve as a coach. Because I believe that people ultimately need to develop their own agency and not just simply offload it onto tech. The tech needs to play the role of supporting actor and the individual is the primary actor.

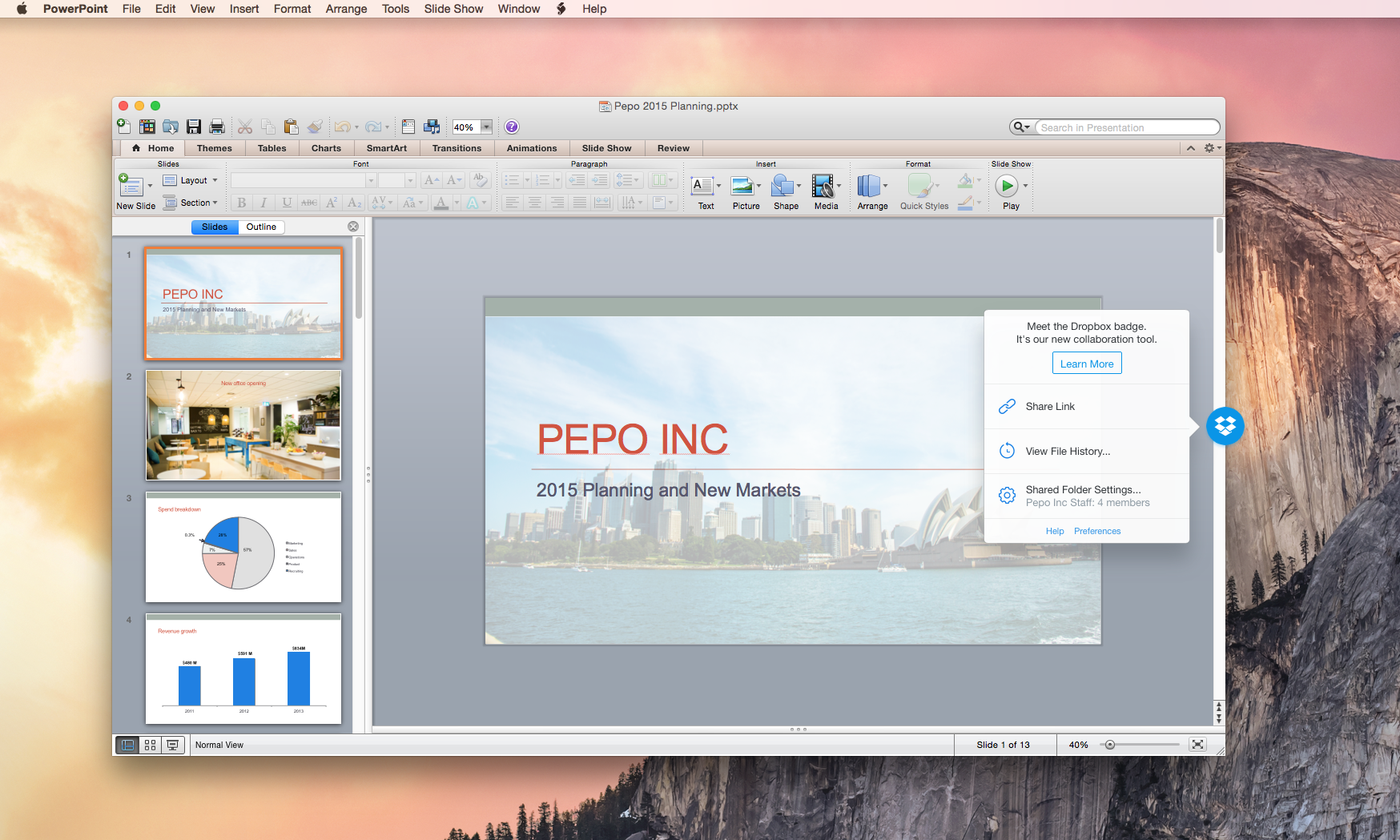

For more of their conversation, listen to Remotely Curious, a Dropbox podcast on remote work.

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_wide%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(3).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/blog%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_wide%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/1080x1080%20(1).webp)

.gif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)