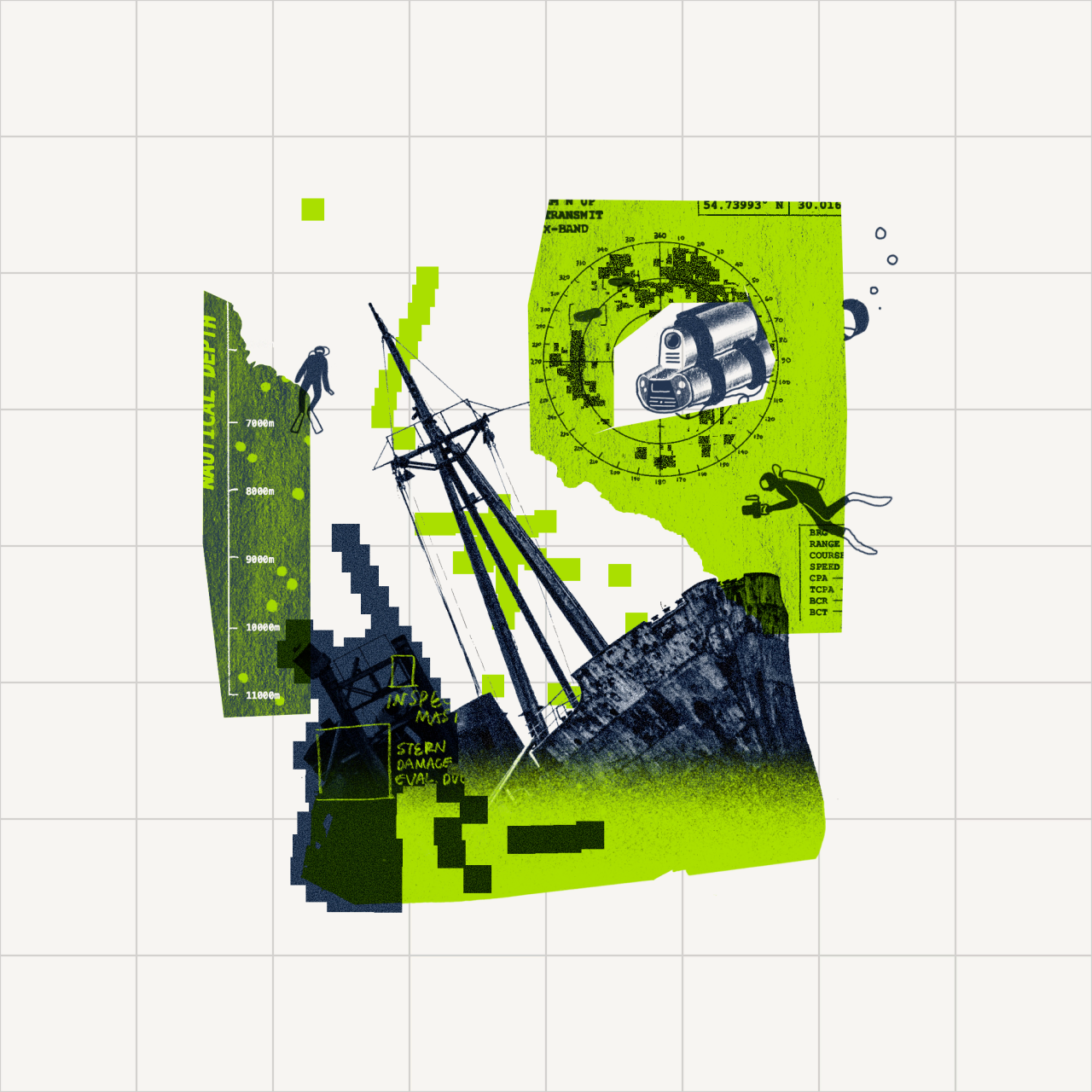

For these shipwreck-hunting humans, AI is part of the crew

Published on September 17, 2025

Very few people get paid to visit shipwrecks—but for Stephanie Gandulla it’s all part of the job. Stephanie is a scuba diver, maritime archeologist, and resource protection coordinator for the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, which lies not far off the coast of Alpena, Michigan. As the name implies, the area is known for its terrible weather—and, as result, its numerous historical shipwrecks. Many of the wrecks are over a century old, so the sanctuary was created to protect them. Around 100 have been found so far, and Gandulla thinks there’s at least that many more to be found.

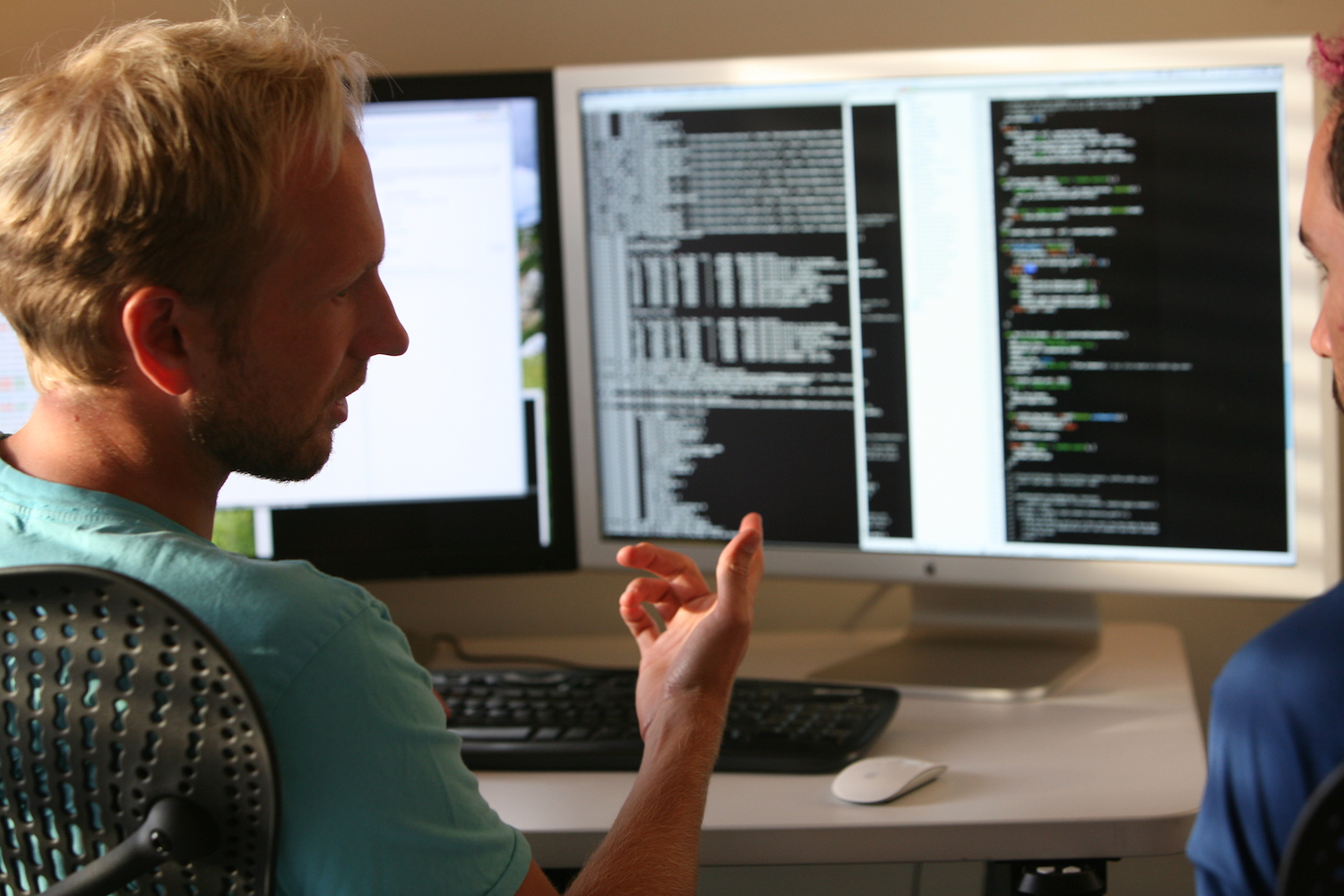

That’s where Katie Skinner comes in. She’s an assistant professor at the University of Michigan and the director of the school’s Field Robotics Group. Skinner and her team have been developing autonomous underwater vehicles that can find new shipwreck sites, all on their own. For humans, a search is costly, time-consuming, manual work. But for AI? Skinner thinks it could help us find answers in a snap.

On season two of the Dropbox podcast Working Smarter, Stephanie and Katie talk about using AI to find shipwrecks in a literal lake of data, so that they can spend less time searching and more time exploring—as only humans can do.

You can read an excerpt of our conversation with Katie below.

~ ~ ~

People have been using underwater robots for decades now to map potential shipwrecks and other sites of interest. What’s the problem with how we’ve traditionally done that work?

It's really time consuming to process the data, to look for new discoveries, and analyze any changes. So we're developing machine learning methods to allow the robot to learn from data in order to detect shipwreck sites [on its own]. In maybe the 10 years I've been doing this, the emergence of AI has really opened up new possibilities for things we couldn't do before. Before, we were thinking about surveying and mapping. Now it’s about how we can efficiently interpret the data that we're getting off of our vehicles—and beyond efficiency, how AI models can actually allow us to find new things or think about problems in a way we haven't thought about them before.

How do you get the robot to understand what it’s looking at?

My grad students spent a lot of time with scientists at Thunder Bay making labels for our data—both for training and evaluating the models we're developing. It took months to curate high-quality labels for shipwrecks from the data that we have across 28 different sites. For our purpose, we focus on the task of shipwreck segmentation. So every pixel is labelled “ship” or “not ship.” We actually label every part of the shipwreck, including the whole wreckage field. We sat down with archeologists who have been to these sites on dives many times and they told us, “Actually, this right here is a piece of wood that was part of the ship.” We went to a very fine-grained level, because we wanted our machine learning methods to be able to segment shipwrecks in that way, so when the robot does close range surveys it knows exactly where the bounds of the shipwreck site are.

So what happens now when you send one of these robots out to go map a potential shipwreck site?

When we get the robot back on the boat with methods that we've developed, we actually can process the data from an hour-long survey in about five minutes—something that might have taken human operators several hours to sort through before. So it really makes the process of detecting targets of interest much faster, which cuts down the time that we have between missions. It means that while we're actually out on the boat doing a survey, we can go back while we're still there and don't have to plan a whole new trip to reinvestigate something we've detected. We can send the robot out to explore and come back with interesting new things that we wouldn't have seen before.

What was that like, the first time you saw the model work the way you hoped it would?

In the second year of the project, we got to test the AI models that we developed. And the first site we went to we had never been to before. We put the robot in the water, waited for it to come back, downloaded the data, and crossed our fingers. It was pretty incredible to see that, within five minutes, it did what we had designed it to do. It was able to give us a segmentation of the shipwreck site—again, one that we had never been to before. So that was pretty exciting to see.

We spend all this time in the lab, testing it on things we've seen before—but then seeing it actually work on a laptop on the boat was like, “Oh, wow. Okay. This can actually be really useful.” And it's something that got us really excited about the possibilities of this work. My overall goal, of course, would be to find a new shipwreck, right? To be able to just deploy a robot out in Thunder Bay, sit on the boat, have it survey for the day and come back and tell me what it found. That’s the dream.

With all of the time that you're saving, what does that mean for the work you do?

An important aspect of saving time is actually saving cost. It’s expensive to have a whole team go out on a boat every day. I hope that by saving both cost and time, we can ask some of the more high-level questions we want to answer. Like, how [else] can we think about looking for new shipwreck sites? There's a lot of work archeologists do that goes into actually thinking about what initial sites we should even survey. All of that takes a lot of time.

Looking to the future, what would a fully autonomous, underwater robotic vehicle do for you and your work that you can't yet do today?

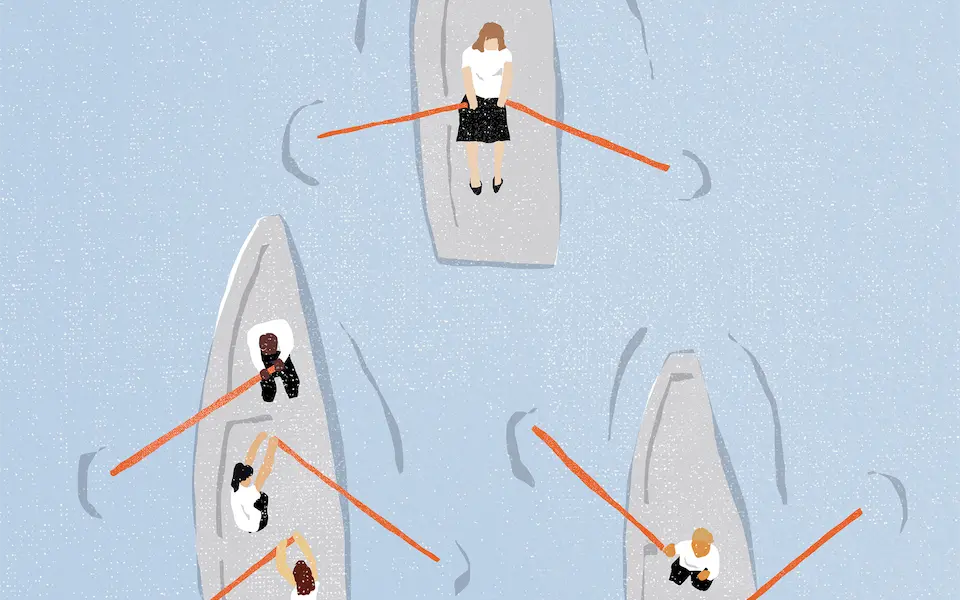

We would be able to deploy these robots to go out and continuously, autonomously map the sea floor, map the lake beds, and detect objects that are interesting for us to be aware of and to have a better understanding of. I really want to someday see us be able to send out fleets of underwater robots—maybe cooperating together to map underwater environments.

Do you think we can get there someday? How far away are we?

Maybe I'm optimistic, but I do think that we can get there. We've gotten further and further on different pieces of this puzzle. I don't know if I could put a time limit on it, but hopefully in my career.

This interview has been edited and condensed. For more interviews and past episodes, visit workingsmarter.ai

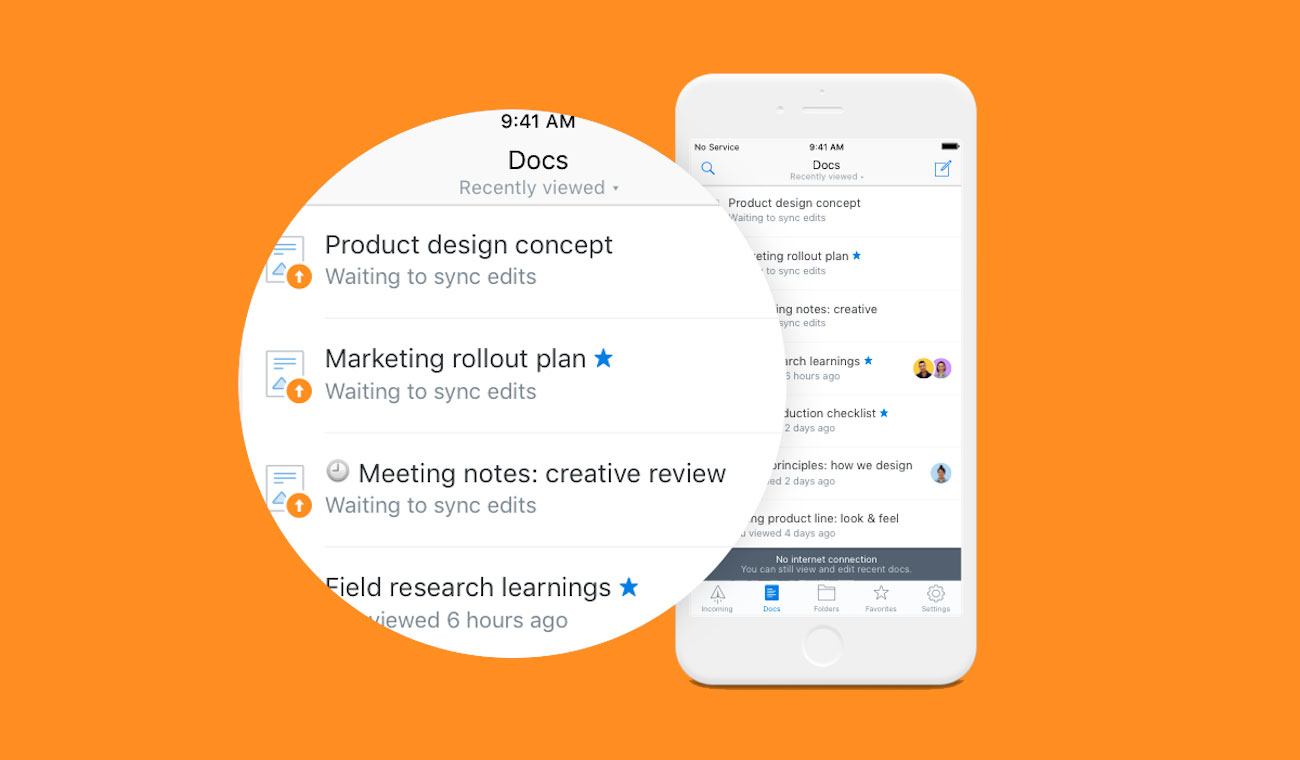

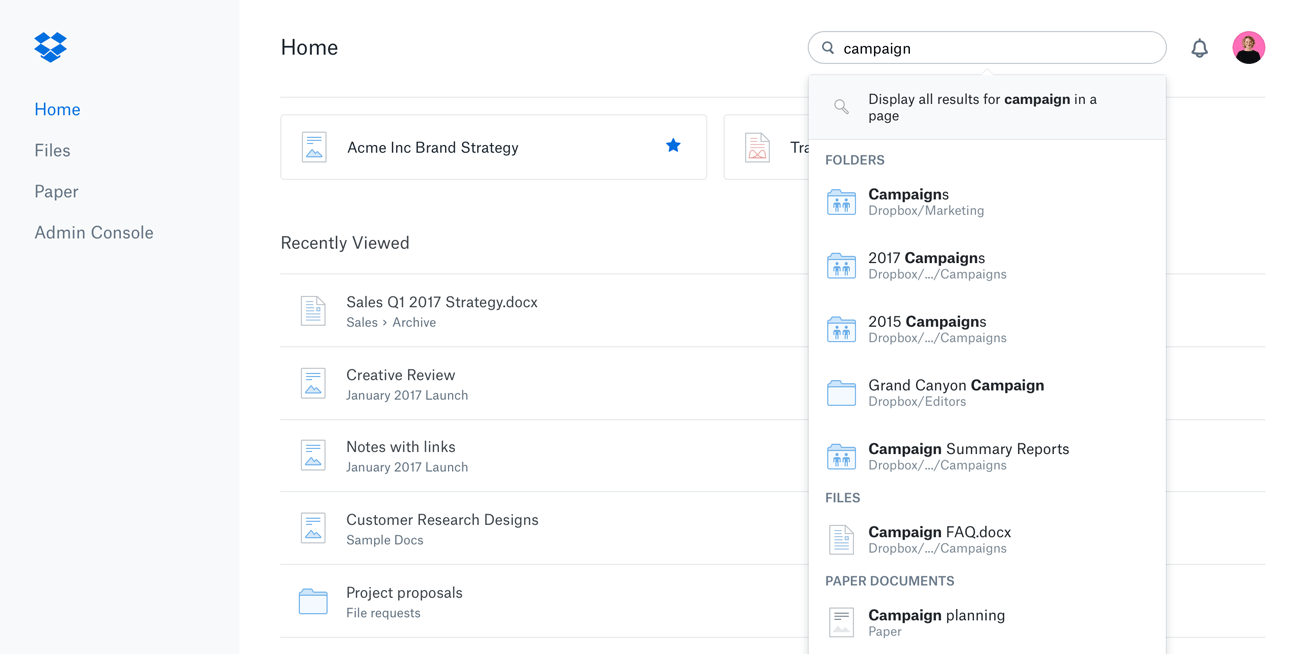

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work

Dropbox Dash: The AI teammate that understands your work

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_wide%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_square%20(3).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/blog%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/hero_wide%20(1).webp)

.png/_jcr_content/renditions/1080x1080%20(1).webp)

.gif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)